Excerpt

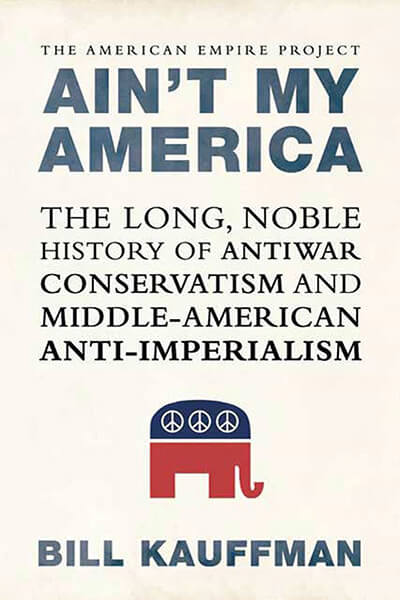

Ain’t My America

The Long, Noble History of Antiwar Conservatism and Middle-American Anti-Imperialism

by Bill Kauffman

Excerpt

Ain’t My America

The Long, Noble History of Antiwar Conservatism and Middle-American Anti-Imperialism

by Bill Kauffman

Introduction

Left stands for peace, right for war; liberals are pacific, conservatives are bellicose. Or so one might conclude after surveying the dismal landscape of the American Right in the Age of Bush II.

Yet there is a long and honorable (if largely hidden) tradition of antiwar thought and action among the American Right. It stretches from ruffle-shirted Federalists who opposed the War of 1812 and civic-minded mugwump critics of the Spanish-American War on up through the midwestern isolationists who formed the backbone of the pre–World War II America First Committee and the conservative Republicans who voted against U.S. involvement in NATO, the Korean conflict, and Vietnam. And although they are barely audible amid the belligerent clamor of today’s shock-and-awe Right, libertarians and old-fashioned traditionalist conservatives are among the sharpest critics of the Iraq War and the imperial project of the Bush Republicans.

Derided as isolationists—which, as that patriot of the Old Republic Gore Vidal has noted, means simply people who “want no part of foreign wars” and who “want to be allowed to live their own lives without interference from government”1—the antiwar Right has put forth a critique of foreign intervention that is at once gimlet-eyed, idealistic, historically grounded, and dyed deeply in the American grain. Just because Bush, Rush, and Fox are ignorant of history doesn’t mean authentic conservatives have to swallow the profoundly un-American American Empire.

Rooted in the Farewell Address of George Washington, informing such conservative-tinged antiwar movements as the Anti-Imperialist League, which said no to U.S. colonialism in the Philippines, finding poignant and prescient expression in the extraordinary valediction in which President Dwight Eisenhower warned his countrymen against the “military-industrial complex,” the conservative case against American Empire and militarism remains forceful and relevant. It is no museum piece, no artifact as inutile as it is quaint. It is plangent, wise, and deserving of revival. But before it can be revived, it must be disinterred.

A note, first, on taxonomy. To label is to libel, or at least to divest the subject of individuating contradictions and qualifications. I have found that the most interesting American political figures cannot be squeezed into the constricted and lifeless pens of liberal or conservative. Nor do I accept the simpleminded division of our lovely and variegated country into red and blue, for to paint Colorado, Kansas, and Alabama requires every color in the spectrum. Right and Left have outlived their usefulness as taxonomic distinctions. They’re closer to prisons from which no thought can escape.

Yet the terms are as ubiquitous as good and evil, and in fact many on the Right do think, Latinately, of their side as dexterous and the Left as sinister. I say it’s time for a little ambidexterity. So my “Right” is capacious enough to include Jeffersonian libertarians and Jefferson-hating Federalists, Senators Robert Taft and George McGovern (yes, yes; give me a chance), dirt-farm southern populists and Beacon Streeters who take hauteur with their tea and jam, cranky Nebraska tax cutters and eccentric Michigan tellers of ghostly tales, little old ladies in tennis shoes marching against the United Nations and free-market economists protesting the draft. My subjects are, in the main, suspicious of state power, crusades, bureaucracy, and a modernity that is armed and dangerous. They are anti-expansion, pro-particularism, and so genuinely “conservative”—that is, cherishing of the verities, of home and hearth and family—as to make them mortal (immortal?) enemies of today’s neoconservatives.

Above all, they have feared empire, whose properties were enumerated well by the doubly pen-named Garet Garrett: novelist, exponent of free enterprise and individualism, and a once-reliable if unspectacular stable horse for the Saturday Evening Post. Writing in 1953, he set down a quintet of imperial requisites.

1. The executive power of the government shall be dominant.

2. Domestic policy becomes subordinate to foreign policy.

3. Ascendancy of the military mind, to such a point at last that the civilian mind is intimidated.

4. A system of satellite nations.

5. A complex of vaunting and fear.2

Between “Constitutional, representative, limited government, on the one hand, and Empire on the other hand, there is mortal enmity,”3 wrote Garrett, who did not burst with confidence that the former would vanquish the latter. He wrote in the final days of the Truman administration. The executive bestrode the U.S. polity. Militarism and the cult of bigness held sway. The blood rivers of Europe had yet to run dry. More than fifty thousand American boys had died—for what?—on the Korean peninsula. Truman had refused to obtain from Congress a formal declaration of war; future presidents would follow suit. The dark night of Cold War was upon us. This was what our forebears had warned against.

Why did these men (and later women) of the “Right” oppose expansion, war, and empire? And, in contemporary America, where have all the followers gone?

From the Republic’s beginning, Americans of conservative temperament have been skeptical of manifest destiny and crusades for democracy. They have agreed with Daniel Webster that “there must be some limit to the extent of our territory, if we are to make our institutions permanent. The Government is very likely to be endangered . . . by a further enlargement of its already vast territorial surface.”4 Is it really worth trading in the Republic for southwestern scrubland? Webster’s point was remade, just as futilely, by the Anti-Imperialist League. It was repeated by those conservatives who supplied virtually the only opposition to the admission of Hawaii and Alaska to the Union. As the Texas Democrat Kenneth M. Regan told the House when he vainly argued against stitching a forty-ninth star on the flag, “I fear for the future of the country if we start taking in areas far from our own shores that we will have to protect with our money, our guns, and our men, instead of staying here and looking after the heritage we were left by George Washington, who told us to beware of any foreign entanglements.”5

Expansion was madness. John Greenleaf Whittier compared its advocates to hashish smokers.

The man of peace, about whose dreams

The sweet millennial angels cluster,

Tastes the mad weed, and plots and schemes,

A raving Cuban filibuster!6

George W. Bush, it is rumored, preferred coke to hash, but his utopian vision of an American behemoth splayed across the globe would be, to conservatives of eras past, a hideous nightmare.

Robert Nisbet, the social critic who was among the wisest and most laureled of American conservatives, wrote in his coruscant Conservatism: Dream and Reality (1986): “Of all the misascriptions of the word ‘conservative’ during the last four years, the most amusing, in an historical light, is surely the application of ‘conservative’ to the [budget-busting enthusiasts for great increases in military expenditures]. For in America throughout the twentieth century, and including four substantial wars abroad, conservatives had been steadfastly the voices of non-inflationary military budgets, and of an emphasis on trade in the world instead of American nationalism. In the two World Wars, in Korea, and in Viet Nam, the leaders of American entry into war were such renowned liberal-progressives as Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt, Harry Truman and John F. Kennedy. In all four episodes conservatives, both in the national government and in the rank and file, were largely hostile to intervention.”7

In the two decades since Nisbet’s observation the historical amnesia has descended into a kind of belligerent nescience. Today’s self-identified conservatives loathe, detest, and slander any temerarious soul who speaks for peace. FDR and Truman join Ronald Reagan in the trinity of favorite presidents of the contemporary Right; those atavistic Old Rightists who harbor doubts about U.S. entry into the world wars or our Asian imbroglios (scripted, launched, and propagandized for by liberal Democrats) are dismissed as cranks or worse. Vice President Dick Cheney, lamenting the August 2006 primary defeat of the Scoop Jackson Democratic senator Joseph Lieberman, charged that the Democrats wanted to “retreat behind our oceans”8—which an earlier generation of peace-minded Republicans had considered a virtuous policy consistent with George Washington’s adjuration to avoid entanglements and alliances with foreign nations.

Felix Morley, the Washington Post editorialist who would have been a top foreign-policy official in the Robert Taft administration, wrote in 1959: “Every war in which the United States has engaged since 1815 was waged in the name of democracy. Each has contributed to that centralization of power which tends to destroy that local self-government which is what most Americans have in mind when they acclaim democracy.”9 Alas, Dick Cheney, the draft-dodging hawk, the anti-gay-marriage grandfather of a tribade-baby, is not an irony man.

I will consider the anti-expansionists of the early Republic in the first chapter. My focus in this book, however, is on “conservative” anti-imperialists of the twentieth century—the American Century, as that rootless son of missionaries Henry Luce dubbed it. The men and women whom I shall profile regarded Lucian expansion, conquest, and war—whether in the Philippines in 1900 or Vietnam in 1968—as profoundly un-American, even anti-American. The American Century, alas, did not belong to the likes of Moorfield Storey, Murray Rothbard, or Russell Kirk. But the American soul does.

These brave men and women also insisted, in the face of obloquy and smears, that dissent is a patriotic imperative. For questioning the drive to war in 1941, Charles Lindbergh would be called a Nazi by the FDR hatchet man Harold Ickes, and for challenging the constitutionality of Harry Truman’s Korean conflict, Senator Robert Taft would be slandered as a commie symp by The New Republic. Patrick J. Buchanan would be libeled as an anti-Semite for noting the role that Israel’s supporters played in driving the United States into the two (the first two?) invasions of Iraq, and the full range of anti–Iraq War right-wingers would be condemned as “unpatriotic conservatives” by National Review in April 2003. Same as it ever was. As Senator Taft lamented in January 1951 during the brief but illuminating “Great Debate” over Korea and NATO strategy between hawkish liberal Democrats and peace-minded conservative Republicans, “Criticisms are met by the calling of names rather than by intelligent debate.”10

In pre-imperial America, conservatives objected to war and empire out of jealous regard for personal liberties, a balanced budget, the free enterprise system, and federalism. These concerns came together under the umbrella of the badly misunderstood America First Committee, the largest popular antiwar organization in U.S. history. The AFC was formed in 1940 to keep the United States out of a second European war that many Americans feared would be a repeat of the first. Numbering eight hundred thousand members who ranged from populist to patrician, from Main Street Republican to prairie socialist, America First embodied and acted upon George Washington’s Farewell Address counsel to pursue a foreign policy of neutrality.

As the America Firsters discovered, protesting war is a lousy career move. Dissenters are at best calumniated, at worst thrown in jail: for standing against foreign wars and the drive thereto Eugene V. Debs was imprisoned (World War I), Martin Luther King Jr. was painted red and spied upon (Vietnam War), and those who have spoken and acted against the Bush-Cheney Iraq War have been subject to a drearily predictable array of insults and indignities.

It has long been so. Edgar Lee Masters, the Spoon River Anthology poet and states’-rights Democrat who threw away his career by writing a splenetic biography of Abraham Lincoln decrying Honest Abe as a guileful empire builder, recalled of the Spanish-American War: “There was great opposition to the war over the country, but at that time an American was permitted to speak out against a war if he chose to do so.”11 Masters had lived through the frenzied persecutions of antiwar dissidents under the liberal Democrat Woodrow Wilson. He had little patience with gilded platitudes about wars for human rights and the betterment of the species. He knew that war meant death and taxes, those proverbial inevitabilities that become shining virtues in the fog of martial propaganda. Masters, in the argot of today’s war party and its publicists, was a traitor, a cringing treasonous abettor of America’s (and freedom’s!) enemies.

Yet Masters and his ilk were American to the core, and the antiwar Middle Americanism they represented has never really gone away. It surfaced even during Vietnam, that showpiece war of the best and brightest establishment liberal Democrats. Although most conservative Republicans were gung-ho on Vietnam, discarding their erstwhile preference for limited constitutional government, the right-wing antiwar banner was carried by such libertarians as Murray Rothbard (who sought, creatively, to fuse Old Right with New Left in an antiwar popular front) and the penny-pinching Iowa Republican congressman H. R. Gross, who said nay to the war on the simple if not wholly adequate grounds that it cost too much.

The Iraq wars of the Presidents Bush have rekindled the old antiwar spirit of the Right, though it is easy to miss in the glare of the bombs bursting in the Mesopotamian air. Indeed, Bush Republicans and pro-war Democrats have fretted mightily over recent surveys from the Council on Foreign Relations showing that the American people are reverting to—horrors!—isolationism, which the CFR defines invidiously as a hostility toward foreigners but which I see as a wholesome, pacific, and very American reluctance to intervene in the political and military quarrels of other nations.

The old American isolationism endures, despite the slurs, despite its utter absence within the corridors of power. President George W. Bush, as messianically interventionist a chief executive as we have ever endured, took out after the bogeyman in his 2006 State of the Union address: “Our enemies and our friends can be certain: The United States will not retreat from the world, and we will never surrender to evil. America rejects the false comfort of isolationism.”12 And America, or rather its masters, chooses the bloody road of expansion and war.

The men who write the words that thud from Bush’s mouth felt compelled to rebuke nameless isolationists because, as a Pew Research Center survey of October 2005 found, 42 percent of Americans agreed that the U.S. “should mind its own business internationally and let other countries get along the best they can on their own.” As a Pew press release noted, over the last forty years “only in 1976 and 1995 did public opinion tilt this far toward isolationism.”

Democrats were “twice as likely as Republicans to say the U.S. should mind its own business internationally,” a sign of just how successful Bush and the neoconservatives have been in reshaping the GOP mind, as it were. (A decade earlier, Pew found no substantial difference in isolationist attitudes among Republican and Democratic partisans.)

Despite the Wilsonian tattoo issuing from the White House and repeated assertions that the U.S. military is constructing a democratic Middle East, Pew found that “promoting democracy in other nations” comes in dead last in the foreign-policy priorities of Americans. Only 24 percent of respondents affirmed that goal, as compared to 84 percent who favored “protecting jobs of American workers” and 51 percent who placed “reducing illegal immigration” atop their list.13 These latter two are classic themes of the isolationist Right, as embedded, for instance, in the presidential campaigns of Patrick J. Buchanan.

There is nothing freakish, cowardly, or even anomalous about these Middle Americans who are turning against foreign war. They are acting in the best traditions of their forebears. But those forebears have been disgracefully forgotten. The history of right-wing (or decentralist, or small-government, or even Republican) hostility to militarism and empire is piteously underknown. The traditions are unremembered. Which is where this book comes in.

The Bush-whacked Right is incorrigibly ignorant of previous “Rights.” For all they know, Robert Taft may as well be Che Guevara. Yet there is a good deal of subsurface grumbling by the Right, among Republican operatives (who understand the potential of an anti-interventionist electoral wave); D.C.-based movement-conservatives, who recall that in the dim mists of time they once spoke of limited government as a desideratum; and at the grassroots level, where once more folks are asking the never-answered question of the isolationists: why in hell are we over there?

Bill Clinton lamented after his 1997 State of the Union address, “It’s hard when you’re not threatened by a foreign enemy to whip people up to a fever pitch of common, intense, sustained, disciplined endeavor.”14 Old-style conservatives would deny that this is ever a legitimate function of the central state. “Sustained, disciplined endeavor” driven by a populace at “fever pitch” and organized by a central state is fascistic. It ill befits the country of Ken Kesey and Bob Dylan and Johnny Appleseed. It sure as hell ain’t my America.

I should own up to my own biases. I belong to no political camp: my politics are localist, decentralist, Jeffersonian. I am an American rebel, a Main Street bohemian, a rural Christian pacifist. I have strong libertarian and traditionalist conservative streaks. I am in many ways an anarchist, though a front-porch anarchist, a chestnut-tree anarchist, a girls-softball-coach anarchist. My politics are a kind of mixture of Dorothy Day and Henry David Thoreau, though with an upstate New York twist. I voted for Nader in 2004 and Buchanan in 2000: the peace candidates. I often vote Libertarian and Green. I am a freeborn American with the blood of Crazy Horse, Zora Neale Hurston, and Jack Kerouac flowing in my veins. My heart is with the provincial and with small places, and it is from this intense localism that my own isolationist, antiwar sympathies derive. I misfit the straitjackets designed by Fox News and the New York Times. So does any American worth the name.

You can have your hometown or you can have the empire. You can’t have both. And the tragedy of modern conservatism is that the ideologues, the screamers over the airwaves, the apparatchiks in their Beltway viper’s den, have convinced the Barcalounger-reclining National Review reader that one must always and forever subordinate one’s place, one’s neighborhood, whether natal ground or beloved adopted block, to the empire.

It isn’t true! It never has been true. There is nothing conservative about the American Empire. It seeks to destroy—which is why good American conservatives, those loyal to family and home and neighborhood and our best traditions, should wish, and work toward, its peaceful destruction. We have nothing to lose but the chains and taxes of empire. And we have a country to regain.

Copyright © 2008 by Bill Kauffman.