Excerpt

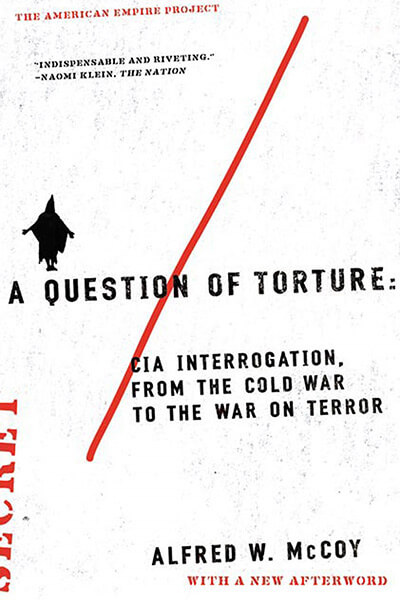

A Question of Torture

CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror

by Alfred McCoy

Excerpt

A Question of Torture

CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror

by Alfred McCoy

Introduction

My work on this book began in another country, in another time, in another lifetime. In the summer of 1933, a grand Pierce-Arrow touring car sped past Switzerland’s historic Schaffhausen castle and crossed into Germany. The powerful steel-cast, straight-eight engine pumped out an unmatched 125 horsepower, as the sedan swept north to the medieval market city of Nuremberg. With its chromed grill, massive front bumper, crouching-archer ornament, and trumpet-shaped head lamps, this automobile seemed a glistening herald of triumphal American engineering, plowing across the Bavarian countryside.

At the wheel, pushing the car to its limit of eighty-five miles an hour, was a German American brewer, Rudolf Piel, touring his father’s homeland in search of the latest technology for the family’s famed Brooklyn brewery. In the passenger seat, his wife, Margarita, watched the usual daredevil driving with a practiced forbearance. In the back, their ten-year old daughter, Peggy, was as always reading, glancing up from time to time at the passing, farms, fields, and once, at a team of oxen that blocked the road. Sitting sentinel at her side was the family’s German shepherd, Teufel.

Reaching Nuremberg, the oversize American sedan entered the town’s medieval walls and twisted its way through the narrow cobbled streets. The passengers’ meandering led to the Rathaus, where they strolled through the grand assembly hall, its high-timbered ceiling soaring and light streaming through leaded windows. With his meticulous way of looking for the serious, the important, Peggy’s father insisted they tour the dungeons below, the “Lochgefangnisse.”

This small family, their little girl in tow, followed a guide as he descended a narrow staircase into the stone foundations of the Rathaus and then through the dungeons, even then famed as exemplars of medieval justice. First they squeezed their way through a series of tiny cells, small wooden rooms built into the stonework, each with a narrow plank bed and low ceiling that made even a minute’s visit seem oppressive.

Inside this dark world, Peggy discovered a new, disturbing feeling akin to despair. The stonework seemed covered with the black grime of centuries, unscrubbed. Because there were no windows, the air was still and heavy. The utter darkness, broken only by a few faint electric bulbs, was frightening.

Moving on, they entered a high-ceiling interrogation chamber with a roped contraption to suspend bound prisoners painfully for questioning beneath a slit window where medieval magistrates had once observed. Near the winch were heavy, hewn stones that could be attached to the feet for increased pain. With her child’s imagination, Peggy knew what must have happened.

The next room held an infinite variety of iron implements for physical torture—countless thumbscrews, calipers, chains, and spiked pressure devices. In their heavy, burnished iron, so perfectly preserved, these all seemed terribly cruel. Then, as the family walked through the dungeon, tunnels, and lanes to a nearby tower, she came face-to-face with the famed Iron Maiden of Nuremberg—an iron-girded wooden box shaped like a bloated giant that crushed its victim between two beds of sharp, elongated iron spikes. Watching from her protected world, the girl thought this was all unimaginably monstrous. Then, the tour done, she emerged into the sunlight stunned and shaken by this visit to what she would later call “the torture museum.”

The Pierce-Arrow swept north, by stages, to relatives in Dusseldorf, to the old family farm near Dortmund, and then east to the capital, where the family settled for a year. Berlin of 1933–1934 was in the throes of a vivid, traumatic time, making Peggy Piel witness to events so monumental, so powerful that they would remain in her memory for a lifetime.

Yet nothing she would see during this that in Berlin’s troubled present could rival her taste of Nuremberg’s past: Not seeing the rapture on the faces of street-side crowds as Hitler passed in an open car. Not watching an entire city freeze in rigid attention while Hitler spoke over the radio—waiters, diners, and trams immobilized by his voice. Not observing the concierge’s son, a Hitler Youth leader, terrorize their apartment building with random raids at all hours in search of subversion. Not even being chased through the streets by a mob of teenage toughs who pelted her with mud and stones, screaming over and over, “American Jew! American Jew!”

When the year was over, the child came home to America, grew up, married a soldier during World War II, and raised two children, telling them of the things she had seen as a girl in Germany. Later, when she became a university professor and gained the habit of speaking with nuance, choosing her words with care, she would still say, “Torture is evil, pure and simple.”

That little girl was, and is, my mother. If I have learned but a fraction of what she tried to teach us, every page that follows bears, in some way, the imprint of her experience. But I cannot, of course, start from her assumption of evil. I must, as an analyst of U.S. policy, begin with a question, asking whether there might not be, in desperate times, some circumstances in which torture is effective, even justified. In short, this is a book about policy, not a study of morality, and it is written largely from a pragmatic perspective, probing the hidden history of torture inside the U.S. intelligence community over the past half century.

Copyright © 2006 by Alfred McCoy