Excerpt

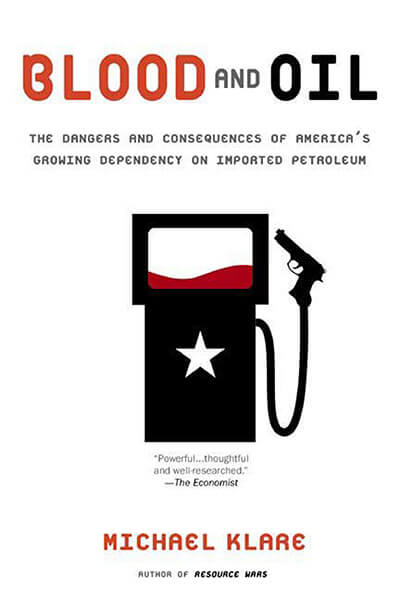

Blood and Oil

The Dangers and Consequences of America's Growing Dependency on Imported Petroleum

by Michael Klare

Excerpt

Blood and Oil

The Dangers and Consequences of America's Growing Dependency on Imported Petroleum

by Michael Klare

1. The Dependency Dilemma:

Imported Oil and National Security

Tampa, Florida, is not one of the places you usually think of as a hub for American relations with the oil kingdoms of the Persian Gulf. It does not, like Houston, play host to any of the giant U.S. oil companies; it does not, like Washington, D.C., house the State Department and foreign embassies; and it does not, like New York, lay claim to the United Nations and the international news media. But Tampa does have something that none of those other cities can claim: the headquarters of the U.S. Central Command (Centcom), the nerve center for all U.S. military operations in the Persian Gulf region, including those now under way in Afghanistan and Iraq. Centcom forces, operating as they do in the greater Middle East, occupy the front lines in the war against terrorism and play a critical role in efforts to prevent the spread of weapons of mass destruction. From its very inception, however, Centcom’s principal task has been to protect the global flow of petroleum.

Situated at MacDill Air Force Base in south-central Tampa, Centcom is one of the five regional “unified commands” that govern American combat forces around the world. (The others are the Southern Command, based in Miami; the European Command, based in Stuttgart; the Pacific Command, based in Honolulu; and the Northern Command, based in Colorado Springs.) It is headed by a four-star general—currently General John P. Abizaid of the U.S. Army—and exercises direct command authority over all U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps contingents deployed in its “area of responsibility” (AOR), covering twenty-five mostly Muslim nations in the Persian Gulf area, the Horn of Africa, the Caspian Sea basin, and Southwest Asia. This vital but turbulent region includes Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen.1

As its recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan indicate, Centcom has emerged as one of the Pentagon’s most important unified commands. It is not, however, the largest or best endowed. The European Command, in Stuttgart, has numerous bases in Europe and incorporates all the American forces assigned to NATO; the Pacific Command, in Honolulu, oversees powerful combat fleets and hundreds of thousands of troops in Asia and the Pacific. Centcom, in contrast, has few permanent operating bases of its own (other than MacDill) and has to borrow troops from the other commands when assembling a force to deploy in its AOR. What makes Centcom distinctive is that its forces inhabit an active war zone where American soldiers are fighting and dying on a daily basis.

The Central Command was formally established only two decades ago, on January 1, 1983. Since then, Centcom forces have fought in four major engagements: the Iran-Iraq War of 1980–88, the Persian Gulf War of 1991, the Afghanistan War of 2001, and the Iraq War of 2003. Centcom was also responsible for enforcing the containment of Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi regime after the completion of Operation Desert Storm. Almost all the American soldiers who have died in combat since 1985 were serving under its authority, including the victims of terrorist attacks at the Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia in June 1996 and aboard the USS Cole in October 2000.

Although Centcom’s AOR stretches more than three thousand miles, from Egypt in the east to Kyrgyzstan in the west, its geographic and strategic heart is the Persian Gulf basin, the home of approximately two-thirds of the earth’s known petroleum reserves. This area contains the world’s five leading producers of oil—Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates—and many of its most important suppliers of natural gas. Every day, tankers carrying approximately 14 million barrels of petroleum traverse the Gulf proper and pass through the narrow Strait of Hormuz on their way to markets around the world. Keeping this channel open and defeating any and all threats to the steady production of Persian Gulf oil is the overriding responsibility of Centcom forces.

The Central Command’s basic mission was originally enunciated in the Carter Doctrine of January 23, 1980, which designated the secure flow of Persian Gulf oil as a “vital interest” of the United States. Claiming that this key interest was threatened by the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan (which had begun in December 1979) and the near-simultaneous rise of a radical Islamic regime in Iran, President Jimmy Carter told Congress that Washington would use “any means necessary, including military force,” to keep the oil flowing.2 At that time, however, the United States had few forces in the Gulf and only a limited capacity to deploy additional troops in the region; moreover, authority over any American forces that might be deployed there was divided between the European and the Pacific commands, complicating coordination. In order to back up his proclamation, Carter established the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) at MacDill Air Force Base and gave it responsibility for combat operations in the Gulf. Three years later, on January 1, 1983, President Ronald Reagan elevated the RDJTF, naming it the Central Command (because it encompasses the “central region” between Europe and Asia) and putting it on an equal footing with the other regional commands.3

Centcom’s critical role in protecting the nation’s and its allies’ oil supply finds blunt expression in the testimony its commanders in chief regularly deliver to Congress. “America’s vital interests in the Central Region are long-standing,” General J. H. Binford Peay III told a House subcommittee in 1997. “With over 65 percent of the world’s oil reserves located in the Gulf states of the region—from which the United States imports nearly 20 percent of its needs; Western Europe, 43 percent; and Japan, 68 percent—the international community must have free and unfettered access to the region’s resources.” Any disruption in this flow, he warned, “would intensify the volatility of the world oil market [and] precipitate economic calamity for developed and developing nations alike.”4 All of Peay’s successors have echoed this judgment.

Centcom’s forces got their first taste of combat in 1987, when President Reagan ordered U.S. warships to escort Kuwaiti tankers—hastily re-flagged with the American ensign—while traversing the Persian Gulf and to protect them from attack by Iran and Iraq, then in the final throes of their bloody eight-year war. Such action was essential, Reagan declared, to demonstrate the “U.S. commitment to the flow of oil through the Gulf.”5 Three years later, in August 1990, President George H. W. Bush used similar language to justify the deployment of Centcom forces in Saudi Arabia, to deter a possible attack by the Iraqi forces then encamped in Kuwait. “Our nation now imports nearly half the oil it consumes and could face a major threat to its economic independence,” he said in a nationally televised address on August 8. Hence, “the sovereign independence of Saudi Arabia is of vital interest to the United States.”6

The ensuing Persian Gulf War introduced the American public and the international press to Centcom’s most memorable leader: General H. Norman Schwarzkopf, the brash and forceful architect of Operation Desert Storm. General Schwarzkopf is widely credited with the dramatic “Hail Mary” maneuver that led to the rapid encirclement and defeat of the Iraqi forces in Kuwait.7 At that point, Schwarzkopf—acting under orders from the president—ceased military operations and commenced what was to become the “containment” of Iraq. Enforcing the containment strategy—including the no-fly zone in southern Iraq and the UN-imposed blockade in the Gulf proper—occupied Centcom forces for the next twelve years, until the onset of Operation Iraqi Freedom in March 2003.

The degree to which the 2003 war with Iraq was driven by American concern over the safety of Persian Gulf oil supplies is a complex and controversial issue that I will examine carefully later in this book. Suffice it to say here that, from the vantage of officers and enlisted personnel in the

U.S. Central Command, the invasion of Iraq is only the latest in a series of military engagements in the Gulf proceeding from the Carter Doctrine. This history helps to explain why the very first military objective of Operation Iraqi Freedom was to secure control over the oil fields and refineries of southern Iraq, and why, following the initial U.S. incursion into Baghdad, American forces seized and occupied the Oil Ministry while allowing looters to overrun all the other government buildings in the neighborhood.8

Although Saddam Hussein no longer controls Iraq, and his military has been largely destroyed, Centcom’s work is far from finished. American troops continue to guard the pipelines that carry Iraqi crude to the Turkish Mediterranean port of Ceyhan and to protect oil facilities elsewhere in the country. Some of this work is being turned over to private guards and Iraqi police units, but American forces will continue to play a crucial role in defending Iraq’s highly vulnerable petroleum infrastructure against attack for some time.9 Elsewhere in the Gulf, Centcom ships and planes continue to monitor the incessant oil-tanker traffic and guard the Strait of Hormuz. Farther north, still other Centcom units serve at American military bases in Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. No other regional command shoulders so many responsibilities or faces so much danger on a day-to-day basis.

From every indication, Centcom’s responsibilities—and the perils they entail—will grow, not diminish, in the years ahead. The United States is becoming ever more dependent on petroleum from the Persian Gulf area and Central Asia, and ensuring access to that energy source will inevitably entangle American forces in the multitude of ethnic, religious, and political conflicts that trouble the region. Notwithstanding the many American troops now deployed in Centcom’s AOR and the many battles they have fought and won, the area is no more stable today than it was in January 1980, when President Carter issued his proclamation. Although we cannot foresee the precise nature and timing of the next crisis the Central Command will address, it’s safe to predict that its forces will see combat in the Persian Gulf once more—and that such intervention will be repeated again and again until the last barrel of oil is extracted from the Gulf ‘s prolific but highly vulnerable reservoirs.

Moreover, soldiers from the other regional commands are increasingly being committed to oil-related operations of this sort. Already troops from the Southern Command (Southcom) are helping to defend Colombia’s Cano Limón pipeline, a vital link between oil fields in the interior and refineries on the coast, which has been under recurring attack from leftist guerrillas. Likewise, soldiers from the European Command (Eurcom) are training local forces to protect the newly constructed BakuTbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline in Georgia. Eurcom also oversees all U.S. forces deployed in Africa (except in the Horn, which falls under Centcom’s jurisdiction) and has begun seeking bases from which to support future operations to defend the region’s oil facilities. Finally, the ships and planes of the U.S. Pacific Command (Pacom) are patrolling vital tanker routes in the Indian Ocean, the South China Sea, and the western Pacific.10

Taken together, these developments lead to an inescapable conclusion: that the American military is being used more and more for the protection of overseas oil fields and the supply routes that connect them to the United States and its allies. Such endeavors, once largely confined to the Gulf area, are now being extended to unstable oil regions in other parts of the world. Slowly but surely, the U.S. military is being converted into a global oil-protection service.

How did this situation arise? Why have America’s armed services been assigned this demanding and hazardous role? What are the long-term consequences of this decision? To answer these critical questions, it is first necessary to look at petroleum itself and consider its pivotal role in shaping the American economy. Likewise, it is essential to assess oil’s place in the evolution of American security policy and the implications of the nation’s growing dependence on imported supplies.

“Petroleum,” the energy expert Edward L. Morse says, “has proven to be the most versatile fuel source ever discovered, situated at the core of the modern industrial economy.”11 This has certainly been the case in the United States, where oil is a major source of energy and a key driver of economic growth. Petroleum provides approximately 40 percent of the nation’s total energy supply—far more than any other source. (Natural gas supplies 24 percent, coal 23 percent, nuclear power 8 percent, and all others 5 percent.) Oil serves many functions—powering industry, heating homes and schools, providing the raw material for plastics and a wide range of other products—but it is in transportation that its role is most essential. At present, petroleum products account for 97 percent of all fuel used by America’s mammoth fleets of cars, trucks, buses, planes, trains, and ships.12

Most analysts believe that oil will remain the nation’s principal source of energy for many years to come. This is so because other sources of energy are either too scarce (natural gas, hydropower), too costly (wind, solar), or too harmful in generating by-products (carbon dioxide in the case of coal, radioactive waste in the case of nuclear power). Petroleum, by contrast, is relatively abundant, reasonably affordable, and generates less CO2 than coal does. So it will likely remain the primary source of fuel for America’s industries, communities, and transportation systems for the foreseeable future. In fact, the Department of Energy predicts that petroleum will account for approximately the same proportion of America’s total energy supply in 2025, 41 percent, that it does today.13

The United States was the first country in the world to develop a large-scale petroleum industry—an endeavor that began in 1859, when pioneering developers struck oil in Titusville, Pennsylvania—and this industry has played a central role in sustaining the nation’s economic growth for the past 145 years. Copious domestic oil output gave rise to America’s first large multinational corporations, among them John D. Rockefeller’s legendary Standard Oil Company, the progenitor of such industry giants as Exxon Mobil, Chevron (now combined with Texaco), Amoco (now part of British Petroleum [BP]), and Atlantic Richfield (now also part of BP). Abundant and relatively cheap oil was also essential to the rise of such other mammoth enterprises as the Big Three automobile manufacturers, DuPont and other chemical companies, and the large airline and freight companies. These firms and others like them have generated much of the nation’s wealth and employed many of its workers over the past century.14

It is nearly impossible to chronicle all the ways petroleum contributes to the vibrancy of the American economy. Because rapid and reliable transportation is so vital to the functioning of virtually every industry and enterprise, an abundant supply of affordable oil has been a major spur of economic growth and expansion. Private automobiles and cheap gasoline made possible the suburbanization of America, with all its housing developments, malls, office parks, and associated infrastructure. Petroleum provides the “feedstock,” or basic raw material, for paints, plastics, pharmaceuticals, textile fibers, and a host of other products. The nation’s highly productive agricultural industries also rely on petroleum to power farm machinery and provide the feedstock for pesticides, herbicides, and other key materials. And the booming tourism and recreation industry utterly relies on affordable car, bus, and airplane travel.15

A painful reminder of the critical role that oil plays in the U.S. economy is the fact that nearly every economic recession since World War II has come on the heels of a global petroleum shortage and an accompanying surge in prices. Many readers will remember the Arab oil embargo and the OPEC price increases of 1973–74, which resulted in endless lines at gas stations and a severe economic contraction. Long gas lines and another contraction followed the Iranian Revolution of 1979, and a similar if shorter episode followed the August 1990 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. More recently, a global shortage of petroleum triggered the lingering economic downturn of 2001–2002 and threatened to slow or abort the recovery of 2004. To be sure, other factors have played a role in these events, but in each case a shortage of petroleum set the downturn in motion.

Just as petroleum fuels the economy, it also plays an essential role in

U.S. national security. The American military relies more than that of any other nation on oil-powered ships, planes, helicopters, and armored vehicles to transport troops into battle and rain down weapons on its foes. Although the Pentagon may boast of its ever-advancing use of computers and other high-tech devices, the fighting machines that form the backbone of the U.S. military are entirely dependent on petroleum. Without an abundant and reliable supply of oil, the Department of Defense could neither rush its forces to distant battlefields nor keep them supplied once deployed there.16

This combination of factors is what makes petroleum central to America’s economic and military strength. “Oil fuels more than automobiles and airplanes,” Robert E. Ebel, of the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told a State Department audience in April 2002. “Oil fuels military power, national treasuries, and international politics.” Far more than a simple commodity to be bought and sold on the international market, petroleum “is a determinant of well being, of national security, and international power for those who possess this vital resource, and the converse for those who do not.”17

For most of the petroleum age, the United States was among those very fortunate nations that possessed this vital resource. From 1860 until World War II, this country was the world’s leading oil producer, easily supplying its own needs and often generating a surplus for export.

Petroleum self-sufficiency played a significant role in America’s economic growth and emerging military predominance. During World War II, for example, the United States was able to extract enough oil from domestic fields to satisfy the massive requirements of its own forces and those of its major allies. American wells supplied six out of every seven barrels of the oil the Allied powers consumed over the course of the war. After World War II, rising U.S. oil output helped generate this country’s great prosperity and kick-start economic recovery in Europe and Japan.18 Secretary of Energy Spencer Abraham boldly affirmed this close relationship between oil supply and global power in a June 2002 speech to U.S. energy company officials: “You and your predecessors in the oil and gas industry played a large part in making the twentieth century the ‘American Century.’ “19

But however accurate in some respects, this characteristically exuberant message conceals a critical flaw: America’s oil inheritance, while abundant, is not limitless. In the late 1940s, the United States began to rely on foreign oil to satisfy rising energy demand, and the proportion of imports has been rising more or less steadily ever since. During the 1950s, foreign oil accounted for 10 percent of total U.S. consumption; in the 1960s, it accounted for about 18 percent, and in the 1970s approximately twice that much.20 For a while, domestic production continued to rise as well, thus mitigating to some degree the economic impact of rising energy imports. But U.S. production began an irreversible decline in 1972, and since then it has taken an ever-expanding flow of imported oil to satisfy rising demand and compensate for the decline in domestic output. Slowly but surely, the United States has become dependent on foreign petroleum for its economic vibrancy. In Ebel’s words, it has gone from being a country for which oil abundance has been a source of security and strength to one for which the converse is true.

The onset of petroleum dependency created a troubling situation for American leaders and the public at large. Briefly stated, abundant petroleum has helped the U.S. economy and the U.S. military dominate the world, and to propel further growth we will have to consume more and more of it, yet the United States is producing less oil, and thus will have to import ever increasing quantities from abroad. At present, the United States—with something less than 5 percent of the world’s total population—consumes about 25 percent of the world’s total supply of oil. In 2025, if current trends persist, we will be consuming half as much petroleum again as we do today; however, domestic production will be no greater than it is today, and so the entire increase in consumption—approximately 10 million barrels of oil per day—will have to be supplied by foreign producers.21 And because we can’t really control what goes on in those countries, we become hostage to their capacity to ensure an uninterrupted flow of petroleum.

And herein lies the dilemma. Oil makes this country strong; dependency makes us weak. It weakens us in a number of ways. First, it leaves us vulnerable to supply disruptions abroad, whether accidental or intentional. Such disruptions, like the oil shocks of 1973–74 and 1979–80, typically result in widespread shortages of oil, sharply higher prices, and a worldwide recession. Dependence also entails a massive shift in economic resources from the United States to our foreign suppliers. Assuming that oil is priced at $30 per barrel, the total bill for imported oil over the next twenty-five years should reach a colossal $3.5 trillion; if oil prices rise above this amount, the bill obviously will be much greater.22 On the political side of the ledger, dependence often requires us to grant all sorts of favors to the leaders of our major foreign suppliers, whether we like them or not. Though they may sell us their petroleum, they frequently expect more than money in compensation: support at the United Nations, transfers of advanced weaponry, military protection, and so forth. As reluctant as our leaders may be to grant such perquisites, they often feel bound to do so to facilitate the flow of oil. Worst of all, dependence can jeopardize our very security, by entangling us in overseas oil wars or by arousing the violent hostility of political and religious factions that resent a U.S. military presence in their midst.23

America’s leaders have never succeeded in resolving the energy/security dilemma. They have sometimes taken this step or that to slow the growth in oil consumption, such as improving the fuel efficiency of American cars. Or they have proposed the exploitation of untapped domestic reserves in protected wilderness areas, such as the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). But they have never embraced a sustained and comprehensive energy strategy for reducing the demand for foreign petroleum. Instead, in order to minimize the nation’s vulnerability to overseas supply disruptions, they have chosen to securitize oil—that is, to cast its continued availability as a matter of “national security,” and thus something that can be safeguarded through the use of military force. As Secretary of Energy Abraham suggested, “energy security is a fundamental component of national security.”24 This premise underlies a great deal of American foreign and military policy since World War II.

The procurement of foreign petroleum first became a national security matter under the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration during the final years of World War II. Although the United States was then the world’s leading producer of oil, President Roosevelt and his aides feared that the accelerated wartime production was rapidly exhausting domestic reserves and hastening the onset of our reliance on imports—a development they thought had grave implications for the nation’s long-term security and well-being. But believing, as they did, that such a reliance was inevitable, they attempted to protect future U.S. energy imports by establishing an American protectorate over Saudi Arabia and a permanent military presence in the Persian Gulf.25 I will discuss the specific steps they took to achieve these ends in chapter 2; the important point here is that Roosevelt set in motion the process of ever-increasing American military involvement in the greater Gulf area.

After World War II, American leaders continued to see foreign petroleum through the lens of national security. Both Presidents Harry S. Truman and Dwight D. Eisenhower regarded the protection of Persian Gulf oil as a vital component of cold-war military strategy, and both introduced major policy initiatives—the Truman and Eisenhower doctrines, respectively—dealing with the strategic equation in the Persian Gulf region. As a result, the United States sharply increased its military aid to friendly producers in the Gulf, especially Saudi Arabia, and sent additional combat forces to the area.26 President John F. Kennedy built on these precedents, ordering U.S. planes to the region in 1963 when Yemeni forces linked to President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt attacked Saudi Arabia.27 That America’s reliance on imported oil was still relatively modest at this point—no more than 20 percent of total consumption— only underscores the degree to which the administration viewed dependency as a significant threat to national security.

Not surprisingly, American leaders grew far more deeply concerned over the implications of dependency as the level of such reliance rose. The share of America’s petroleum supply that is accounted for by imports crossed the 30 percent mark in 1973 and the 40 percent mark in 1976, reaching 45 percent in 1977.28 It was this trend, along with the Iranian revolution of 1978–79 and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, that led President Carter to regard the safe flow of oil from the Gulf as a matter of national security and to order the formation of what later became the

U.S. Central Command. As I noted earlier, the Carter Doctrine provided the justification for the protection of Kuwaiti oil tankers during the later stages of the Iran-Iraq War and the deployment of American forces in Saudi Arabia following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.

The expulsion of Saddam Hussein’s forces from Kuwait in February 1991 and the subsequent containment of Iraq produced a degree of stability in the Gulf that supported an increase in petroleum output and a drop in prices. These developments, in turn, helped foster the growing American reliance on foreign oil: the share of imports in the nation’s total annual supply rose from 42 percent in 1990 to 49 percent in 1997. And then the once unthinkable occurred: in April 1998, American dependence on imported petroleum crossed the 50 percent mark. It increased still more in the months that followed, and so the United States entered the twenty-first century among those great powers with a net reliance on foreign oil. (See figure 1.)

As we crossed the psychologically important 50 percent threshold, a fresh debate over the strategic implications of dependency broke out among American policy makers.29 Some analysts argued that petroleum, having become a globally traded commodity with many willing suppliers, no longer required government involvement in its procurement.30 Others argued that it would take concerted action at the national level to mitigate the handicaps of dependency. This latter group proposed all sorts of initiatives both to reduce American reliance on imported oil and to cushion the impact of future disruptions in the global flow of energy. Their ideas ranged from a major expansion of the Strategic Petroleum

Reserve (a vast reservoir of stockpiled oil available for use in an emergency) to the rapid introduction of alternative forms of energy, such as wind and solar.31 Still, most policy makers anticipated a deepening dependence on imports, and with it an ever-increasing role for American soldiers in guarding the global flow of oil. “As the world’s only superpower, [the United States] must accept its special responsibilities for preserving access to worldwide energy supply,” a high-level task force established by the Center for Strategic and International Studies concluded in 2000.32

This debate gained wide attention during the 2000 presidential election, when for the first time oil dependency and energy security became important campaign issues. With worldwide shortages sending up oil prices and California reeling from blackouts, both major candidates spoke of a looming energy crisis and promised forceful action to overcome it. After taking office, President George W. Bush pledged to make energy security a top White House priority. “This administration is concerned about [the energycrisis],”he told a group of energyofficials on March19,2001, “and we will make a recommendation to the country as to how to proceed.”33

In the weeks that followed, Bush identified our growing petroleum dependency as a significant threat to the nation’s security. “If we fail to act,” he declared in May 2001, “our country will become more reliant on foreign crude oil, putting our national energy security into the hands of foreign nations, some of whom do not share our interests.”34 To counter this danger, the White House proposed a variety of measures: drilling in ANWR and other protected sites, speeding the development of hybrid (gas/electric) and hydrogen-powered vehicles, and pursuing other technological innovations. But nothing in these proposals really sought to reverse the nation’s growing reliance on imported oil; nor did they eliminate America’s dependence on the Persian Gulf. Instead, Bush—like every one of his predecessors—turned to the U.S. military to provide insurance against the hazards associated with dependency.

In the early years of the twenty-first century, then, the United States is no closer to solving the dilemma of dependency than it was in Roosevelt’s era. We remain highly reliant on foreign petroleum, much of it from the Gulf and other conflict-prone areas. This reliance exposes us to a host of perils, including supply disruptions, unsavory alliances, and entanglement in deadly oil wars. For many policy makers, this is a tolerable level of threat: if dependence on imports is what it takes to satisfy America’s gargantuan thirst for petroleum, that is just the way it is. But dependency is not a static condition. The farther we head into the future, the deeper our reliance on imported energy will be and the greater the perils we will face. To fully appreciate the severity of our dilemma, we need to project current trends into the future and see where they are taking us.

The first of these trends is the steady, unrelieved growth of our dependence on imports. The reasons for this growing dependency is simple: America’s oil consumption is rising while domestic production is falling. The situation will continue as far into the future as we can see, according to the long-range projections of the Department of Energy. Its Annual Energy Outlook 2004 foresees that total U.S. oil consumption will rise from an average of 19.7 million barrels per day in 2001 to 28.3 million barrels in 2025, an increase of 44 percent. At the same time, domestic crude-oil production is expected to drop from 5.7 to 4.6 million barrels per day. The drop will be offset to some degree by a slight gain in the production of liquid petroleum from natural gas, but the yawning gap between consumption and production—a gap that only imports can fill—will continue to widen throughout this period.35 (See figure 2.)

The reasons for the decline in domestic petroleum output are steeped in geology and history. At its founding, the United States was blessed with a substantial but fixed amount of conventional (i.e., liquid) petroleum. Debate rages over the magnitude of that original inheritance—some geologists set it at 345 billion barrels of oil, others at considerably less—but most experts agree that the country’s largest and most productive fields have already been discovered and exploited.36 Because naturally occurring petroleum is stored in porous rock under considerable pressure, any given reservoir or producing area will initially yield great quantities of oil—the well-known gusher effect—but output will drop as time goes on and underground field pressure diminishes. The United States achieved maximum domestic production in 1972; petroleum output has been in decline ever since. The development of new fields in Alaska can slow the rate of decline to some extent but cannot reverse this long-term process of depletion.37

The factors behind the increase in consumption are more diffuse but no less identifiable. Petroleum is an unusually efficient and versatile energy source, performing many vital functions for individuals and for the economy as a whole. These include, as I already noted, its many industrial and agricultural applications and its use as a home heating fuel. But to explain the steady increase in consumption we must look primarily to transportation, which accounts for about two-thirds of our current petroleum usage. The numbers are staggering: as Americans buy more and bigger vehicles and drive them longer distances every year, the 13.5 million barrels per day devoted to transportation use in 2001 will jump to an estimated 20.7 million in 202538—at which point such usage will commandeer approximately three-quarters of America’s total petroleum supply and over one-sixth of the entire world’s.39

Consumption on this scale cannot help but boost the demand for imports. “The single biggest factor in our ever-increasing dependency on foreign oil is our seemingly endless capacity to consume,” former deputy secretary of the Treasury Stuart E. Eizenstat told Congress in 2002. “And, on this subject, the facts are overwhelmingly clear: increased capacity to supply energy from domestic sources cannot match the increased demand that American consumers will have for oil.”40 Accordingly, our dependence on foreign petroleum will continue to grow, rising from 55 percent of U.S. consumption in 2001 to an estimated 58 percent in 2010, 66 percent in 2020, and 70 percent in 2025—the furthest into the future that the Department of Energy is currently prepared to project.41

The second trend we need to consider is that more and more of our imported oil will be coming to us from countries that are unstable, unfriendly, or located in the middle of dangerous areas (or some combination of all three). And it is this trend, more than any other, that makes our reliance on foreign energy so worrisome. After all, we wouldn’t be so anxious about our growing dependency if all our energy was coming to us from Canada, Norway, Australia, and other friendly producers located in peaceful parts of the world. But those countries have limited reserves and are slowly running out of oil, and so it is to the Middle East, Central Asia, Africa, and other less stable but more prolific areas of the world that we will increasingly have to turn for our future petroleum supplies.

Here, too, it is geology that underlies our predicament. Conventional petroleum is not distributed evenly across the planet; it is highly concentrated in a few giant reservoirs. The United States has the good fortune of owning a number of these, as do a few other industrialized nations— Canada, Russia, and North Sea countries. But most of the earth’s remaining large deposits are in the developing world, notably the Persian Gulf area, the Caspian Sea basin, northern and western Africa, and South America. And because the industrialized nations generally started exploiting their own deposits at the beginning of the petroleum era, most of the world’s as yet untapped oil is now lodged in the developing areas.42

As figure 3 shows, six Persian Gulf countries—Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Kuwait, Iran, and Qatar—jointly possess 674 billion barrels of proven reserves, or about 64 percent of the world’s known supplies. Venezuela, Nigeria, and Mexico jointly claim another 114 billion barrels (11 percent of known reserves), and Russia and the Caspian Sea states have some 77 billion barrels (7 percent of reserves). This leaves only 18 percent of the world’s remaining petroleum supply in the hands of all other countries, including the United States and its European allies.

It doesn’t take a vivid imagination to grasp the essence of America’s energy predicament: only the Middle East and other regions that have long suffered from instability and civil unrest have sufficient untapped reserves to satisfy our (and the world’s) rising petroleum demand in the years ahead. Like it or not, for as long as we continue to rely on petroleum as a major source of energy, our security and our economic well-being will be tied to social and political developments in these unpredictable and often unfriendly producers. Just how tight this bond has become was made painfully evident in the spring of 2004, when violence in three countries— an assault on an offshore oil terminal in Iraq, a series of bombings and shootings in Saudi Arabia, and the killing of oil workers in Nigeria— depressed global petroleum output and produced record-high gasoline prices in the United States.

Our biggest problem, of course, is our growing reliance on the oil kingdoms of the Persian Gulf. No matter how hard the United States tries to diversify its energy imports by turning to producers in other regions, it will still need to acquire more and more oil from the Gulf, the only region whose reserves are large enough to satisfy the rising U.S. and international demand. And sustained dependence on Persian Gulf oil means continued vulnerability to the political unrest, conflict, and terrorism that has long plagued the region. “In the end,” former deputy secretary Eizenstat told Congress, “our dependence on Persian Gulf oil in general and Saudi oil in particular leaves us vulnerable to attack, both abroad and at home.”43

In an effort to reduce America’s exposure to this danger, successive administrations have attempted to increase the nation’s reliance on producers in other areas of the world, particularly Africa, Latin America, and the Caspian Sea basin. But there is no reason to assume that these non-Gulf suppliers ultimately will prove any more safe and reliable than those in the Middle East. “Even a cursory glance at the list of [major oil suppliers] reveals that most have either experienced noteworthy internal stress in the past or contain incipient sources of stress that could flare up in the future,” the energy task force established by the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) noted in its November 2000 report. While we can assume that the North Sea countries and North America will remain stable, “it is not difficult to conceive of future situations in most of the other [suppliers] that could lead to internal strife at a level sufficient to cause a reduction of oil exports.”44

The third critical trend follows from the second. The growing American reliance on unstable suppliers in dangerous parts of the developing world is creating social, economic, and political pressures that are exacerbating local schisms and so increasing the risk of turmoil and conflict. This is the case for a number of reasons. First, the conspicuous presence of U.S. oil firms is bound to arouse hostility from people who reject American values or resent the great concentration of wealth and power in America’s hands. Second, the very production of oil in otherwise underdeveloped societies often skews the local economy—funneling vast wealth to a few and thus intensifying the preexisting antagonism between the haves and the have-nots.

That the presence of U.S. oil companies in the Middle East foments resentment is nothing new; Al Qaeda was by no means the first anti-American or anti-Western organization to target foreign oil facilities and pipelines. But the projected expansion of the American presence in the area, most notably in Iraq, is certain to trigger fresh hostility from such groups. Indeed, the U.S.-protected oil infrastructure in Iraq has already come under repeated attack by opponents of the occupation, severely disrupting American efforts to restore Iraqi production and thereby help finance the costs of reconstruction. In May 2004, moreover, several gunmen attacked the headquarters of an American oil company in Saudi Arabia, killing five employees and wounding several others before they were themselves slain. A more conspicuous U.S. presence in other Gulf countries is likely to provoke similar expressions of anti-American venom.45

The growing American reliance on alternative producers in Africa, Asia, and Latin America could also provoke hostility of this sort. In some cases, it will stem from the same sort of religious extremism as in the Middle East. There are already offshoots of Al Qaeda in Central Asia and the Caucasus region and even in parts of Africa. But there are also other forms of violent opposition in these areas. In Colombia, for example, several revolutionary guerrilla groups have already targeted U.S.-linked oil installations. Venezuela, Mexico, and parts of Africa also harbor guerrillas and militant groups with radical agendas. New U.S. oil facilities in these areas will in many cases invite a new round of anti-American violence.

The risk of disorder and conflict in these countries has a good deal to do with the destabilizing impact of oil production itself. When countries with few other sources of national wealth exploit their petroleum reserves, the ruling elites typically monopolize the distribution of oil revenues, enriching themselves and their cronies while leaving the rest of the population mired in poverty—and the well-equipped and often privileged security forces of these “petro-states” can be counted on to support them. When the divide between privileged and disadvantaged coincides with tribal or religious differences, as it often does, violence is a likely outcome. The Western press may describe such strife as “ethnic” in character, but it comes largely from the perversive effects of oil production.46

The dangers arising from this phenomenon received particular emphasis from the energy task force established by CSIS in 2000. Many of the non-Gulf suppliers upon which the United States is coming to rely, the group noted, “share the characteristics of ‘petro-states,’ whereby their extreme dependence on income from energy exports distorts their political and economic institutions, centralizes wealth in the hands of the state, and makes each country’s leaders less resilient in dealing with change but provides them with sufficient resources to hope to stave off necessary reforms indefinitely.” There is, then, “a significant risk that a crisis in one or more of these key energy-producing countries could occur during the span of the 20 years at the beginning of the century.”47

All of which leads to the fourth and final worrisome trend: to an ever-increasing extent, all other oil-consuming nations will have to draw on the same unstable sources of petroleum as will the United States. Europe and Japan have, of course, long relied on the Middle East and Africa for a large share of their energy requirements, but now China and other rapidly industrializing countries will join them in competing for this petroleum. According to the Department of Energy, oil consumption by developing Asian nations (all but Australia, Japan, and New Zealand) will double over the next twenty-five years, jumping from 15 to 32 million barrels per day. China’s consumption alone will climb from 5.0 to 12.8 million barrels, while India’s will rise from 2.1 to 5.3 million barrels.48 Because these countries, and other rising powers like them, have only limited domestic supplies of their own, they will be forced to jostle with the United States, Europe, and Japan in seeking access to the few producing zones with surplus petroleum, greatly exacerbating the already competitive pressures in these highly volatile areas.

At the very least, these pressures will lead to periodic shortages and price spikes, causing worldwide economic instability. This peril can only increase as many older reserves become depleted and global supplies begin to dwindle. Experts disagree as to when the world’s oil fields will attain maximum (or “peak”) production and begin an irreversible decline—some say this will occur by 2010, others in the second or third decade of this century—but all acknowledge that the planet’s original petroleum inheritance has been substantially exploited and that a reduction in output is inevitable.49 (We’ll come back to this point in chapter 7.) The eventual contraction of global oil supplies will produce economic hardships aplenty, but we face an even greater danger: that China, the United States, and other countries will respond to scarcity by emphasizing the security dimensions of energy and strengthening their military ties with friendly producers in the Gulf and other producing areas. Russia, China, and the United States are all supplying arms and military services to states in these areas already, and the tempo of these activities is rising. As I will argue in chapter 6, this behavior could lead to a classic great-power geopolitical struggle in the oil zones—significantly increasing the risk that a localized conflict might escalate into something far greater.

In summary, then, four key trends will dominate the future of American energy behavior: an increasing need for imported oil, a pronounced shift toward unstable and unfriendly suppliers in dangerous parts of the world; a greater risk of anti-American or civil violence, and rising competition for what will likely prove a diminishing supply pool. Clearly, the perils of dependency are growing more severe. Yet American leaders are trapped in their same old policy paralysis, proposing feeble steps to reduce our reliance on imported oil even as they acquiesce in our ever-increasing dependency.

If history is any guide, U.S. policy makers will be tempted to respond to the dependency dilemma by relying on military means to ensure the uninterrupted flow of energy. And, as before, the burden will fall on the officers and the enlisted personnel of the U.S. Central Command. At the same time, soldiers from other regional commands, including Southcom, Eurcom, and Pacom, will be assigned similar tasks.

The implications for American society are grim. Senior officials appear to believe that the use of military force is not just a legitimate but also an effective response to foreign threats to the flow of petroleum. When Presidents Kennedy, Reagan, Bush senior, and Bush junior ordered American troops into combat in the Gulf, they certainly thought so. But the Gulf is no more stable today than it was before Washington launched these costly operations. And it should be obvious by now that the use of force can have unintended and perilous consequences. For example, when the United States sent warships to protect Kuwaiti oil tankers in 1987–88, the Iranians regarded the move as part of a covert U.S. strategy to aid their opponents, the Iraqis, and so Tehran grew even more hostile toward the United States. Meanwhile, America’s indirect support of Iraq in that conflict undoubtedly contributed to Saddam Hussein’s sense of invincibility—and so influenced his decision to invade Kuwait in August 1990.50 As our growing reliance on military force parallels our growing dependence on imported energy, the risks of miscalculation are bound to increase. Indeed, the magnitude of this danger became terribly obvious in late 2003 and early 2004, when the American troops who had assumed responsibility for protecting Iraq’s vulnerable oil infrastructure found themselves under almost daily attack from opponents of the occupation.

The economic consequences of these developments are equally grim. To begin with, we will have to devote vast sums of money—hundreds of billions of dollars per year—to maintain our military presence in the Persian Gulf and other volatile oil regions. This expenditure comes, of course, on top of the hundreds of billions of dollars we will have to pay for all this imported petroleum. Such mammoth outlays will sap the vigor of the U.S. economy and deplete the Treasury of the funds we need to address our domestic concerns, such as our fraying educational and health-care systems. Most terrible of all, perhaps, is the huge moral cost of Washington’s growing subservience to the autocratic and often anti-American regimes that govern many of the world’s leading oil-producing countries.

None of these far-reaching implications, it appears, has played any part in the policies the current American leadership have chosen to pursue. Our existing policies seem to rest on the delusion that an uninterrupted supply of abundant and cheap energy will be ours forever, despite all the evidence to the contrary. Yes, lip service is being paid to the need for energy independence—most notably in the drive to initiate oil drilling in ANWR—but nothing proposed by President Bush or any other senior White House official will actually reverse the trends I have outlined. Yet without a decisive change in policy the United States will sink deeper and deeper into its dependence on foreign oil, with all the costs—including those measured in human blood—that this condition entails. Only by subjecting these policies to close and careful scrutiny, as I have attempted to do in the following chapters, and by devising alternative energy strategies will it be possible for us to avoid either the perils of dependency or the unconscionable costs they incur.

Copyright © 2005 by Michael Klare