Excerpt

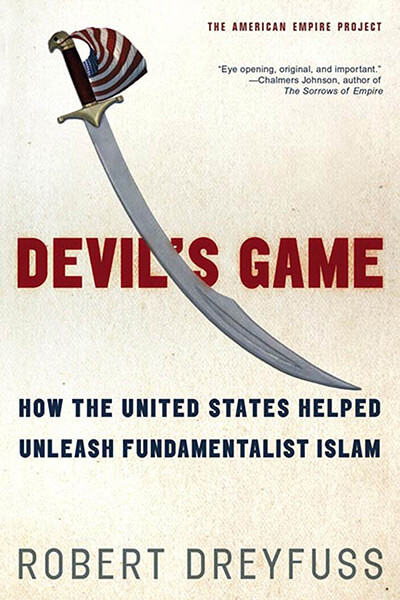

Devil’s Game

How the United States Helped Unleash Fundamentalist Islam

by Robert Dreyfuss

Excerpt

Devil’s Game

How the United States Helped Unleash Fundamentalist Islam

by Robert Dreyfuss

Introduction

I

There is an unwritten chapter in the history of the Cold War and the New World Order that followed. It is the story of how the United States—sometimes overtly, sometimes covertly—funded and encouraged right-wing Islamist activism. Devil’s Game attempts to fill in that vital missing link.

Vital because this little-known policy, conducted over six decades, is partly to blame for the emergence of Islamist terrorism as a worldwide phenomenon. Indeed, America’s would-be empire in the Middle East, North Africa, and Central and South Asia was designed to rest in part on the bedrock of political Islam. At least that is what its architects hoped. But it proved to be a devil’s game. Only too late, after September 11, 2001, did Washington begin to discover its strategic miscalculation.

The United States spent decades cultivating Islamists, manipulating and double-crossing them, cynically using and misusing them as Cold War allies, only to find that it spawned a force that turned against its sponsor, and with a vengeance. Like monsters imbued with artificial life, radical imams, mullahs, and ayatollahs stalk the landscape, thundering not only against the United States but against freedom of thought, against secular science, against nationalism and the left, against women’s rights. Some are terrorists, but far more are just medieval-minded religious fanatics who want to turn the calendar back to the seventh century.

During the Cold War, from 1945 to 1991, the enemy was not merely the USSR. According to the Manichean rules of that era, the United States demonized leaders who did not wholeheartedly sign on to the American agenda or who might challenge Western and in particular U.S. hegemony. Ideas and ideologies that could inspire such leaders were suspect: nationalism, humanism, secularism, socialism. But subversive ideas such as these were also the ones most feared by the nascent forces of Muslim fundamentalism. Throughout the region the Islamic right fought pitched battles against the bearers of these notions, not only in the realm of intellectual life but in the streets. During the decades-long struggle against Arab nationalism—along with Persian, Turkish, and Indian nationalism—the United States found it politic to make common cause with the Islamic right.

More broadly, the United States spent many years trying to construct a barrier against the Soviet Union along its southern flank. The fact that all of the nations between Greece and China were Muslim gave rise to the notion that Islam itself might reinforce that Maginot Line–style strategy. Gradually the idea of a green belt along the “arc of Islam” took form. The idea was not just defensive. Adventurous policy makers imagined that restive Muslims inside the Soviet Union’s own Central Asian republics might be the undoing of the USSR itself, and they took steps to encourage them.

The United States played not with Islam—that is, the religion, the traditional, organized system of belief of hundreds of millions—but with Islamism. Unlike the faith, with fourteen centuries of history behind it, Islamism is of more recent vintage. It is a political creed with its origins in the late nineteenth century, a militant, all-encompassing philosophy whose tenets would appear foreign or heretical to most Muslims of earlier ages and that still appear so to many educated Muslims today. Whether it is called pan-Islam, or Islamic fundamentalism, or political Islam, it is an altogether different creature from the spiritual interpretation of Muslim life as contained in the Five Pillars of Islam. It is, in fact, a perversion of that religious faith. That is the mutant ideology that the United States encouraged, supported, organized, or funded. It is the same one variously represented by the Muslim Brotherhood, by Ayatollah Khomeini’s Iran, by Saudi Arabia’s ultra-orthodox Wahhabism, by Hamas and Hezbollah, by the Afghan jihadis, and by Osama bin Laden.

II

The United States found political Islam to be a convenient partner during each stage of America’s empire-building project in the Middle East, from its early entry into the region to its gradual military encroachment, to its expansion into an on-the-ground military presence, and finally to the emergence of the United States as an army of occupation in Iraq and Afghanistan.

In the 1950s, the enemy was not only Moscow but the Third World’s emerging nationalists, from Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt to Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran. The United States and Britain used the Muslim Brotherhood, a terrorist movement and the grandfather organization of the Islamic right, against Nasser, the up-and-coming leader of the Arab nationalists. In the CIA-sponsored coup d’état in Iran in 1953, the United States secretly funded an ayatollah who had founded the Devotees of Islam, a fanatical Iranian ally of the Muslim Brotherhood. Later in the same decade, the United States began to toy with the notion of an Islamic bloc led by Saudi Arabia as a counterpoint to the nationalist left.

In the 1960s, despite U.S. efforts to contain it, left-wing nationalism and Arab socialism spread from Egypt to Algeria to Syria, Iraq, and Palestine. To counter this seeming threat, the United States forged a working alliance with Saudi Arabia, intent on using its foreign-policy arm, Wahhabi fundamentalism. The United States joined with King Saud and Prince Faisal (later, King Faisal) in pursuit of an Islamic bloc from North Africa to Pakistan and Afghanistan. Saudi Arabia founded institutions to mobilize the Wahhabi religious right and the Muslim Brotherhood. Saudi-backed activists founded the Islamic Center of Geneva (1961), the Muslim World League (1962), the Organization of the Islamic Conference (1969), and other organizations that formed the core of an international Islamist movement.

In the 1970s, with the death of Nasser and the retreat of Arab nationalism, the Islamists became an important prop beneath many of the regimes tied to the United States. The United States found itself allied with the Islamic right in Egypt, where Anwar Sadat used that country’s Islamists to build an anti-Nasserist political base; in Pakistan, where General Zia ul-Haq seized power by force and established an Islamist state; and in Sudan, where the Muslim Brotherhood’s leader, Hassan Turabi, marched toward power. At the same time, the United States began to see Islamic fundamentalism as a tool to be used offensively against the Soviet Union, above all in Afghanistan and Central Asia, where the United States used it as sword aimed at the Soviet Union’s underbelly. And as Iran’s revolution unfolded, latent sympathy for Islamism—combined with widespread U.S. ignorance about Iran’s Islamist currents—led many U.S. officials to see Ayatollah Khomeini as a benign figure, admiring his credentials as an anti-communist. As a result, the United States catastrophically underestimated his movement’s potential in Iran.

Even after the Iranian revolution of 1979, the United States and its allies failed to learn the lesson that Islamism was a dangerous, uncontrollable force. The United States spent billions of dollars to support an Islamist jihad in Afghanistan, whose mujahideen were led by Muslim Brotherhood–allied groups. The United States also looked on uncritically as Israel and Jordan covertly aided terrorists from the Muslim Brotherhood in a civil war in Syria, and as Israel encouraged the spread of Islamism among Palestinians in the occupied territories, helping to found Hamas. And neoconservatives joined the CIA’s Bill Casey in the 1980s in secret deals with Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini.

By the 1990s, the Cold War was over. The political utility of the Islamic right now seemed questionable. Some strategists argued that political Islam was a new threat, the new “ism” replacing communism as America’s global opponent. That, however, wildly exaggerated the power of a movement that was restricted to poor, undeveloped states. Still, from Morocco to Indonesia, political Islam was a force that the United States had to deal with. Washington’s response was muddled and confused. During the 1990s, the United States faced a series of crises with political Islam: In Algeria, the United States sympathized with the rising forces of political Islam, only to support the Algerian army’s crackdown against them—and then Washington kept open a dialogue with the Algerian Islamists, who increasingly turned to terrorism. In Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood and its offshoots, including a violent underground movement, posed a dire threat to President Mubarak’s regime; yet the United States toyed with supporting the Brothers. And in Afghanistan, shattered after the decade-long U.S. jihad, the Taliban won early American support. Even as Osama bin Laden’s Al Qaeda took shape, the United States found itself in league with the Islamic right in Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the Arab Gulf.

And then came 9/11.

After 2001, the Bush administration appeared to sign on to the neoconservative declaration that the world was defined by a “clash of civilizations,” and launched its global war on terrorism, targeting Al Qaeda—the most virulent strain of the very virus that the United States had helped create. Still, before, during, and after the invasion of

Iraq—a socialist, secular country that had long opposed Islamic fundamentalism—the United States actively supported Iraq’s Islamic right, overtly backing Iraqi Shiite Islamists, from Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani to radical Islamist parties such as the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq and the Islamic Call (Al-Dawa), both of which are also supported by Teheran’s mullahs.

III

The vaunted clash of civilizations, that tectonic collision between the West and the Islamic world, if that’s what it was, began inauspiciously. Amid the wreckage of World War II, America stumbled willy-nilly into the Middle East, into a world it knew little about. If the United States made mistakes in dealing with Islam in the second half of the twentieth century, it was in part because Americans were so profoundly ignorant about it.

Until 1941 the Middle East, for young America, was a fearsome and wonderful place, a fantasyland of sheikhs and harems, of turbaned sultans, of obscene bath houses and seraglios, of desert oases, pyramids, and the Holy Land. In early literature—novels, poems, travelogues—it was a place of mystery and intrigue, inhabited by the unsavory and the irreligious. Its people were often portrayed as scimitar-waving “Mussulmen” and “Mohammedans,” uncivilized and uncouth. It was the land of pirates and “Turks,” a term that retains its pejorative connotation today.

Since its appearance in 1869, Mark Twain’s The Innocents Abroad has come to symbolize a peculiarly American sort of naïve blundering overseas. Yet few realize that Twain, perhaps America’s most acute satirist and observer, used the book to describe a months-long sojourn in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. It was hugely influential among nineteenth-century U.S. readers. But Twain unfortunately contributed to, and took advantage of, built-in prejudice against things Islamic. Meandering through Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine, Twain seems to be fairly holding his nose, marveling at the barbarism he is surveying. Dwellings are “tastefully frescoed aloft and alow with disks of camel dung placed there to dry.” Damascus (“How they hate a Christian in Damascus!”) is the “most fanatical Mohammedan purgatory out of Arabia.” He added: “The Damascenes are the ugliest, wickedest looking villains we have seen.” Comparing the Holy Land to a classical engraving of Nazareth, Twain wrote:

But in the engraving there was no desolation; no dirt; no rags; no fleas; no ugly features; no sore eyes; no feasting flies; no besotted ignorance in the countenances; no raw places on the donkey’s backs; no disagreeable jabbering in unknown tongues; no stench of camels; no suggestion that a couple of tons of powder placed under the party and touched off would heighten the effect and give to the scene a genuine interest and charm which it would always be pleasant to recall.

By the early twentieth century—with the advent of World War I, the forced disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, and the start of the British-sponsored “Arab Awakening,” led by the likes of Winston Churchill, T. E. Lawrence (“of Arabia”), and Gertrude Bell—the modern Middle East had begun to intrude on the American consciousness. Still, it was filtered through a layer of romanticism and ignorance. Lawrence’s sexually charged, desert-romantic accounts, including his famous Seven Pillars of Wisdom, became U.S. bestsellers, as did oasis-to-oasis travelogues by various adventurers. For most Americans, the Middle East was most memorably encapsulated in film and song. Rudolf Valentino’s The Sheik (1921) embodied what would become the standard-issue American idea of the Arab, along with its accompanying 1921 song, “The Sheik of Araby,” whose lyrics included the vaguely threatening: “At night, when you’re asleep / Into your tent I’ll creep.” Its influence lasted decades. Benny Goodman recorded the song in 1937, as did the Beatles in 1962 and Leon Redbone in 1977.

Little if any professional American Middle East expertise existed in the years leading up to World War II. From the nineteenth century until well into the twentieth, pretty much the only Americans who ventured into the region were members of a band of Protestant missionaries, educators, and doctors who took it upon themselves to bring the gospels to the heathen masses and to preach among the Christians of the Ottoman Empire, in Syria and Lebanon especially. Pioneers such as Daniel Bliss, his son Howard Bliss, and the Dodge brothers (Reverend David Stuart Dodge and William Early Dodge), who built and ran Syrian Protestant College—renamed the American University of Beirut in the 1920s—and Mary Eddy, a missionary’s daughter who founded a clinic in Lebanon, alighted on the shores of the Ottoman Empire’s Arab provinces. The Blisses, Dodges, and Eddys would become the parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents of America’s priesthood of “Arabists” who emerged after World War II.

IV

In 1945 Franklin Delano Roosevelt went east in search of oil—and found Islam. He conducted a fateful shipboard encounter with the king of Saudi Arabia, Ibn Saud, and for the United States, it marked the real start of its political and military engagement with the region.

Flushed with victory, the United States found itself in the role of a worldwide superpower. Its activism then was naïve in the extreme—endearingly so for its partisans, and frighteningly so for others. The post–World War II generation of U.S. leaders believed wholeheartedly that the American spirit would conquer all, figuratively speaking—or, if necessary, on the ground in real life. This was, after all, Henry Luce’s “American Century.”

The Middle East was then emerging as the most strategically vital area outside the industrial West and Japan. Though it lacked expertise, language skills, and cultural familiarity with the region’s complex civilization, the United States was called to its imperial mission by the very logic of its immense power. In Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, General Cummings presciently described the inexorable growth of American power that would be unleashed by World War II:

I like to call it a process of historical energy [says Cummings]. There are countries that have latent powers, latent resources, they are full of potential energy, so to speak. . . . As kinetic energy a country is organization, coordinated effort. . . . Historically, the purpose of this war is to translate America’s potential energy into kinetic energy. . . . When you’ve created power, materials, armies, they don’t wither of their own accord. Our vacuum as a nation is filled with released power, and I can tell you that we’re out of the backwaters of history now.

But as America’s energy flowed into the Islamic world, the United States began its long-running engagement with little or no comprehension of the forces it was dealing with.

Until after the Second World War, Middle East studies in the United States were virtually nonexistent or relegated to a subset of theology. Partly sponsored by the government, centers for Middle Eastern affairs began springing up after 1947, when Princeton University created the first Near East center in the United States. But it would be many years before the United States would have a cadre of academic experts who had a grasp of Islamic politics, culture, and religion.

From FDR on, leading U.S. politicians were prisoners of misguided stereotypes. They seemed entranced by the almost otherworldly appearance of their Arab interlocutors. FDR, after meeting Ibn Saud, returned to Washington and “could not shake the image of the hawk-like Saudi monarch, ensconced in a gold chair and surrounded by six slaves.” Harry Truman, two years later, described a leading Saudi official as a “real old biblical Arab with chin whiskers, a white gown, gold braid, and everything.” And Eisenhower dismissed the Arabs as “a very uncertain quantity, explosive and full of prejudices.” The official record is full of such uninformed stereotyping of Arabs and Muslims by U.S. officials. For the next sixty years, the handful of American Arabists who actually knew something about the Middle East would try to combat those stereotypes. But they would fail.

V

The American attachment to a romanticized fantasy of Arab life and a racist-fed, religious disdain for the Arabs’ supposed heathenism proved a deadly combination when the time came for America to engage itself politically and militarily in the Middle East. Perhaps those stereotypes led American policy makers to see Muslims as fierce warriors. Perhaps they believed that the fanaticism of their religious tenets would lead them to resist atheistic communism. Perhaps it was the notion that in southwest Asia the traditional religious establishment was a bulwark of the status quo. But it never dawned on U.S. officials that Islamist organizations such as the Muslim Brotherhood were a qualitatively different phenomenon from the comprador clerical establishment. Certainly, as the Cold War progressed, the big enemy, the USSR, and its alleged accomplice, Arab nationalism, seemed to have a common enemy: Islam.

In some ways, the Cold War itself began in the Middle East. President Harry Truman proclaimed U.S. responsibility for Greece and Turkey, replacing Great Britain in that role, in 1947, and confronted the Soviet Union in northern Iran’s Azerbaijan. England’s imperial presence was shrinking: London abandoned Greece and Turkey, then India and Palestine, and the retreat was on—with only the United States to fill the vacuum, an allegedly tempting target for Soviet expansion. (Later scholarship would show that neither Stalin nor Khrushchev had either the intention or the capability to seize control of the Persian Gulf and the Middle East.)

The strategic importance of the Middle East was obvious to all: it was (and is) the indispensable source of energy for America’s allies in Europe and Japan. At the time, the United States did not depend on the Persian Gulf for oil, relying instead on Venezuela and Texas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma. But Europe and Japan desperately needed the Gulf for day-to-day survival. It is no exaggeration to say that U.S. strategists realized that the defense of Western Europe was inconceivable without a parallel plan to control the Gulf. Despite important internal tensions among the Western powers, they forged a series of alliances in the region: NATO, the abortive Middle East Defense Organization, the Baghdad Pact, CENTO—all directed against the USSR. More quietly Washington and London supported the Islamic right against the left in country after country and encouraged the emergence of an “Islamic bloc.”

For those who knew little about the religion and culture of the Middle East—presidents, secretaries of state, CIA directors—the Islamic right seemed like a sensible horse to ride. They could identify with people inspired by deep religious belief, even if the religion was an alien one. In their search for tactical allies, Islam seemed like a better bet than secularism, since the left-wing secularists were viewed as cats’-paws for Moscow, and the centrist ones were dangerously opposed to the region’s monarchies and traditional elites. In the aftermath of World War II, the list of nations ruled by kings included not only Saudi Arabia and Jordan, but Egypt, Iraq, Iran, and Libya.

By the 1950s, the military-intellectual complex of Middle East studies was up and running in many U.S. universities, producing Arabists and Orientalists who were called on by policy makers for advice in grappling with the region’s complexities. The CIA and the State Department gobbled up Ivy League graduates who spoke Arabic, Turkish, Farsi, Urdu, and other Middle East languages, and a core of U.S. government Arabists emerged with at least a working understanding of the region. Yet, by their own testimony, few of them learned much about Islam or Islamism, concentrating instead on the nuts-and-bolts economic and political questions. Most of the Arabists were secularists, and did not have much sympathy for fundamentalist Islam. Many, in fact, instead sympathized broadly with Arab nationalism. Many of them saw Islam as the bygone symbol of a past era.

As the Cold War unfolded, however, State Department and CIA officers who sided with Arab nationalism were increasingly ignored. Their views were attacked by Cold Warriors, and by the supporters of Israel, who were determined to undermine anyone who considered himself or herself “pro-Arab.” By the 1970s, the very term Arabist had become indelibly tainted. Since then, pro-Zionist activists have piled on, waging an ideological blitzkrieg against those Arabists who remained in government or academia. Robert D. Kaplan’s tendentious 1993 book, The Arabists: Romance of an American Elite, marked the high point of this effort. Ever since its publication, attacking Arabists has become a cottage industry. Virtually all of them were excluded from prewar planning on Iraq. To a man, most Arabists were strongly opposed to the preemptive war. But by excluding them, the Bush administration guaranteed that planning for the war would be carried out by know-nothings.

VI

Some may argue that the United States created neither Islam nor its fundamentalist variant, and that is true. But here we need to consider an extended analogy with America’s Christian right.

Conservative and evangelistic Christians have been present in large numbers in America since the colonial era. But in another sense, the emergence of the Christian right in the United States can be dated to the late 1970s, with the formation of the Rev. Timothy LaHaye’s California alliance of churches, the creation of the Moral Majority by LaHaye and Jerry Falwell, and the role of those two men and others in the rise of the Council on National Policy, the Christian Coalition, and organizations like Pat Robertson’s broadcast empire and Dr. James Dobson’s Focus on the Family. Until then, conservative Christians were a politically inchoate force. Relentlessly organized over the past three decades, they have become a self-conscious, politically powerful movement.

The same is true for the Islamic right. The reactionary tendency within Islam goes back thirteen centuries. From Islam’s earliest years, obscurantists, anti-rationalists, and Koran literalists competed with more enlightened, progressive, and moderate tendencies. In more recent times, Muslim reactionaries have been a drag on modernization, opposing progressive education, liberalization, and human rights. But it wasn’t until the creation of the pan-Islamic movement of Jamal Eddine al-Afghani in the late 1800s, the founding of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt by Hassan al-Banna in 1928, and the creation of Abul-Ala Mawdudi’s Islamic Group in Pakistan in 1940 that the Islamic right had its LaHayes, its Falwells, and its Robertsons. Those early Islamists sharpened the culture wars in the Middle East just as their Christian right counterparts did in the United States, and for the same reasons.

Just as the Christian right found support from wealthy right-wing donors, especially oil men from Texas and the Midwest, the Islamic right won financial support from wealthy oil men, too—namely, the royal families atop Saudi Arabia and the Gulf. And just as the Christian right formed a politically convenient alliance with right-wing Republicans, the Islamic right established a similar understanding with America’s right-wing foreign policy strategists. In fact, support for the Christian right and the Islamic right converged neatly during the Reagan administration, which eagerly sought alliances with both. So blinded were some Americans by the Cold War that militant Christian-right activists and fervent Zionist partisans of Israel cheerily supported Islamist fanatics in Afghanistan.

The analogy between Christian and Islamic fundamentalists holds in other areas, too. Both exhibit an absolute certainty about their beliefs and they tolerate no dissent, condemning apostates, unbelievers, and freethinkers to perdition. Both believe in a unity of religion and politics, the former insisting that America is a “Christian nation,” the latter that Muslims need to be ruled either by an all-powerful, religio-political caliphate or by a system of “Islamic republics” under an ultra-orthodox version of Islamic law (sharia). And both encourage a blind fanaticism among their followers. It’s no accident that among followers of both Christian and Islamic fundamentalism, the world indeed appears to be engaged in a clash of civilizations.

VII

A war on terrorism is precisely the wrong way to deal with the challenge posed by political Islam.

That challenge comes in two forms. First, there is the specific threat to the safety and security of Americans posed by Al Qaeda; and second, there is a far broader political problem created by the growth of the Islamic right in the Middle East and South Asia.

In regard to Al Qaeda, the Bush administration has willfully exaggerated the size of the threat it represents. It is not an all-powerful organization. It cannot destroy or conquer America, and it does not pose an existential threat to the United States. It can kill Americans, but it has never had access to weapons of mass destruction, and it almost certainly never will. It does not possess large numbers of cells, assets, or agents inside the United States, although after 9/11 the U.S. attorney general made the unfounded charge that Al Qaeda had as many as 5,000 operatives in America. None of the many hundreds of Muslims arrested or detained after 9/11 were found to have terrorist connections. In three and a half years after 9/11, not a single violent act by Al Qaeda—or any other Islamic terrorist group—occurred in the United States: no hijackings, no bombings, not even a shot fired. No ties were ever proved linking Al Qaeda to Iraq—or to any other state in the Muslim world: not to Syria, not to Saudi Arabia, not to Iran. In short, the threat from Al Qaeda is a manageable one.

Using the U.S. military in conventional war mode is not the way to attack Al Qaeda, which is primarily a problem for intelligence and law enforcement. The war in Afghanistan was wrongheaded: It failed to destroy Al Qaeda’s leadership, it failed to destroy the Taliban, which scattered, and it failed to stabilize that war-torn nation more than temporarily, creating a weak central government at the mercy of warlords and former Taliban gangs. Worse, the war in Iraq was not only misguided and unnecessary, but it was aimed at a nation that had absolutely no links to bin Laden’s gang—as if, said an observer, FDR had attacked Mexico in response to Pearl Harbor. The ham-handed use of the armed forces against a nonstate actor like Al Qaeda is useless and self-defeating. Like some grotesque ancient legend, for every head lopped off by laser-guided missiles, Marine-led raids into Islamist redoubts, Israeli gunship attacks on Hamas and Hezbollah enclaves, and cruise missile attacks on remote strongholds, three new heads grow in its place. But because the Afghan and Iraq wars fit nicely with the Bush administration’s broader policy of empire building and preemptive war, and because they allowed the United States to construct a vast political-military enterprise stretching from East Africa deep into Central Asia, those two wars went forward. A problem that could have been dealt with surgically—using commandos and Special Forces, aided by tough-minded diplomacy, indictments and legal action, concerted international efforts, and judicious self-defense measures—was vastly inflated by the Bush administration.

Still, Al Qaeda can be defeated.

The larger problem, that of the growing strength of Islamic fundamentalism in the Middle East and Asia, is far more complicated.

Naturally, the first problem is related to the second. Unless the Islamic right is stopped, it is possible that Al Qaeda could resuscitate itself. Or, as in Iraq after the U.S. invasion, new Al Qaeda–style organizations might emerge by drawing on anti-American anger and resentment. Or, one of the other Islamic-right terrorist groups, such as Hamas or Hezbollah, might metastasize from a group with a mostly local focus to one with larger, international ambitions. The violence-prone and terrorism-inclined groups in the Middle East draw financial support, theological justification, and legions of recruits from among the more established Islamic fundamentalist institutions that have sprung up in the past three decades in virtually every Muslim country. Like a kettle of water boiling on a stove, out of which only a small volume of steam steadily escapes into the air, in the Middle East the forces associated with political Islam are kept simmering. Out of it, a steady stream of radicals is constantly emitted—extremists who are immediately absorbed by one of the already existing terrorist groups.

So what can the United States do to turn down the heat? To lower the political temperature underneath the Islamist movement?

First, the United States must do what it can to remove the grievances that cause angry Muslims to seek solace in organizations like the Muslim Brotherhood. Not all of these grievances, of course, are caused by the United States, and not all of them can be softened or ameliorated by U.S. actions. At the very least, however, the United States can take important steps that can weaken the ability of the Islamic right to harvest recruits. By joining with the UN, the Europeans, and Russia, the United States can help settle the Palestinian-Israeli conflict in a manner that guarantees justice for the Palestinians: an independent state that is geographically and economically viable, tied to the withdrawal of illegal Israeli settlements, an Israeli return roughly to its 1967 borders, and a stable and equitable division of Jerusalem. That, more than any other action, would remove a global casus belli for the Islamic right.

Second, the United States must abandon its imperial pretensions in the Middle East. That will require the withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan and Iraq, the dismantling of U.S. military bases in the Persian Gulf and facilities in Saudi Arabia, and a sharp reduction in the visibility of the U.S. Navy, military training missions, and arms sales. Many U.S. diplomats who have worked in the region know that the provocative U.S. presence in the Middle East fuels anger and resentment. The United States has no claim to either the Persian Gulf or the Middle East, whose future economic ties and political relationships can and must be determined solely by the leaders of the region’s states, even if it redounds to the detriment of U.S. interests.

Third, the United States must refrain from seeking to impose its preferences on the region. Since 2001, the United States has done incalculable damage by demanding that the “greater Middle East” conform to American visions of democracy. To be sure, for the more radical idealists in the Bush administration, Bush’s call for democracy in the Arab world and Iran is seen primarily as a pretext for more intrusive U.S. involvement in the region. Even taken at face value, however, the initiative ignores the fact that the nations of the Middle East must find democracy at their own pace and in their own time. An obsessive drive for democratic reform in the region is self-defeating and insulting to the states and peoples of the Middle East. Some of those states may be ready for reform, and some may not. Democratic changes that end up empowering the Islamic right and catapulting the Muslim Brotherhood to power in Cairo, Damascus, Riyadh, or Algiers will not serve their intended purpose. They will only deliver additional states into the hands of the Islamists. The United States should adopt a hands-off policy in connection with democracy in the Islamic world.

And fourth, the United States must abandon its propensity to make bellicose threats directed at nations in the Middle East, including those—such as Iran and Sudan—that are still under Islamist rule. The wave of Islamism may not yet have crested. Other nations may succumb to its tide before it recedes, since it is a force that has gathered momentum for decades. But the United States must get used to the fact that threats of force and imperial-sounding diktats strengthen Islamism. They do not diminish it.

The true emancipation of the Middle East will require action by the secular forces in the region to uplift, educate, and modernize the outlook of people who have been captured by Islamism. It is an effort that will take decades, but it must begin now. There is nothing about Islam that requires it to remain mired in the seventh-century belief that the Koran must govern the world of politics, education, science, and culture. It means changing a culture that allows millions of deluded Muslims to think that back-to-basics fundamentalism is somehow an appropriate answer to twenty-first-century problems and concerns. Fundamentalism, whether it takes the form of Islamism, or whether it appears in the form of America’s Christian right or Israel’s ultra-Orthodox settler movement, is always a reactionary force. In the Muslim world, a rational division of the secular and the divine is far from unheard of. Tens of millions of Muslims are able to separate their religious beliefs, held privately, from their politics, just as millions of Muslims, Christians, and Jews do in the United States. It is they—the true silent majority—who must seize the initiative from the fundamentalists. They may ask for, and should receive, support from civil society in the West: from NGOs and universities, from research centers and think tanks, and more.

The peoples of the Middle East must engage not only in nation building but in “religion building.” As the hothouse temperatures in Middle East political discourse are lowered, Muslim religious scholars, philosophers, and social scientists can come together in a great debate to hammer out a twenty-first-century vision of a tolerant, modern Islam, to create a new culture no longer held hostage by self-dealing mullahs and ayatollahs. A consensus can emerge organically in the Muslim world that reinterprets ancient texts and traditions in a manner appropriate to an enlightened world outlook, and then that consensus must find its way into every nook and cranny, beginning in the major cities—Istanbul, Cairo, Baghdad, Karachi, Jakarta—and spreading to every village and mosque. It will mean reforming the educational curriculum in the Muslim world, deemphasizing religious universities and so-called madrassas in favor of modern education. It will require new mass-media outlets in places where they can flourish, and the use of radio, satellite television, and the Internet to reach places where they cannot. All this will take many years. It cannot occur unless the armed conflicts that roil the region are ended, and unless economic conditions move steadily upward. Religion building, like nation building, can take a long, long time.

Copyright © 2005 by Robert Dreyfuss