Excerpt

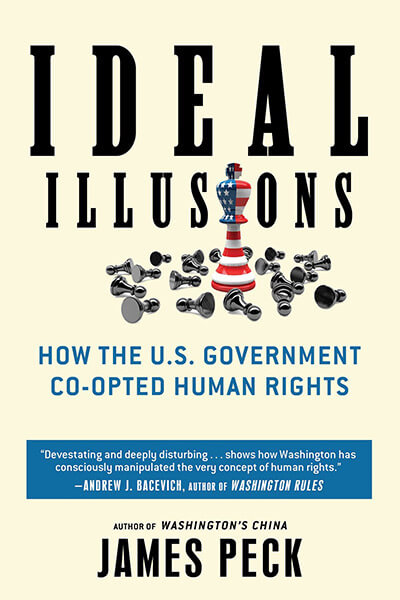

Ideal Illusions

How the U.S. Government Co-opted Human Rights

by James Peck

Excerpt

Ideal Illusions

How the U.S. Government Co-opted Human Rights

by James Peck

Introduction

“Follow an idea through from its birth to its triumph,” Bertrand de Jouvenel observed in his 1948 volume On Power, “and it becomes clear that it came to power only at the price of an astounding degradation of itself. The result is not reason which has found a guide but passion which has found a flag.”1 The widely heralded rise of human rights is not free of such complications. For the history of human rights in the United States—as a movement, as an impassioned language of good intentions, and as an invocation of American idealism—owes far more to the inner ideological needs of Washington’s national security establishment than to any deepening of conscience effected by the human rights movement. Thousands of national security documents (from the CIA, the National Security Council, the Pentagon, think tanks, and U.S. government development agencies) reveal how Washington set out after the Vietnam War to craft human rights into a new language of power designed to promote American foreign policy. They shed light on the way Washington has shaped this soaring idealism into a potent ideological weapon for ends having little to do with human rights—and everything to do with extending America’s global reach.

This obviously isn’t the way human rights leaders have understood the movement’s history. For years they extolled its rise as the triumph of a compelling new moral vision that began with the United Nations’ Universal Declaration on Human Rights in 1948. Out of the reaction to Nazi atrocities, goes the popular narrative, came human rights. Never again would the world stand by in the face of wholesale torture and murder. As human rights became the vocabulary of a vibrant new conception of public good, it promised a sense of solidarity beyond borders, a voice raised on behalf of victims everywhere. By the late 1970s, these early hopes and aspirations had come to flourish in a vigorous movement developing in think tanks, foundations, law schools, UN forums, congressional committees, professional associations, and international nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

The United States, with its longstanding ideals and its traditional respect for civil liberties, was a natural ally, a powerful force for global human rights, according to Amnesty International USA.2 The greatest advantage of Human Rights Watch, wrote its longtime director, Aryeh Neier, was its “identification with a country with a reputation for respecting rights.”3 Of course, the movement’s leaders note, Washington itself has committed some terrible human rights violations—CIA-fomented coups, renditions, Guantánamo. But these and similar “mistakes” or “shortsighted strategic calculations” could not permanently tarnish Washington’s moral authority. When mistakes or crimes occurred, those committed to opposing such egregious acts saw their task as shaming Washington into changing its ways.

At the same time, the willingness of American citizens to expose their own government’s brutalities offered further evidence of freedom at work. For the movement’s leaders and for many ordinary citizens, the ability to criticize was inextricably paired with the nation’s deeper virtue. No other country enjoyed such immunity. Indeed, where the countless human rights abuses committed by the Soviet Union, China, and other nations exposed who they really were, our own were aberrant—a reflection of who we really weren’t. Whatever moral equivalence there was among atrocities did not extend to the parties committing them. American policies were fundamentally progressive. With all these views Washington’s foreign policy leaders heartily concurred.

Of course, when a government and its critics share the same language, they are not necessarily saying the same thing. But adept leaders, as Harold Lasswell noted in his classic 1927 study Propaganda Technique in the World War, know that “more can be won by illusion than coercion.”4 And no ideological formulation has been more astutely propagated by Washington for the past four decades than the notion that a “rights-based” United States is the natural proponent of human rights throughout the world. In part, the rise of human rights recapitulates the old tale of popular idealism seeking to affect power, and power, in turn, shrewdly subverting that idealism to its own ends. Even as the human rights community has methodically focused on Washington’s—and others’—many violations, it has largely recoiled from analyzing the fundamental structures of American power. As a result, it has unwittingly served some of Washington’s deepest ideological needs.

Not enough attention has been paid to the interweaving of idealism and national security concerns, yet it is here that the real history of human rights can be found. Human rights erupted into the mainstream of public debate only because two quite distinct needs came together. On one side, a profound revulsion over the Vietnam War led to the weakening of the anticommunist consensus. Appalled by Cold War rationales and tactics (overthrowing regimes, assassinating leaders, training torturers, supporting dictatorships), human rights advocates mobilized against both American “excesses” and Soviet “crimes,” documenting in particular the atrocities of American-backed military regimes throughout Latin America, from Guatemala to Chile. On the other side, Washington was desperate for new ideological weapons to justify—both at home and abroad—its global strategies. Human rights advocates sought to infuse Washington’s policies with their high-minded ethos just as Washington was fashioning a rights-based vision of America to support its resurgent global aims.

A central question is: who influenced whom? Human rights leaders are convinced they pressured Washington into taking up their cause. Yet in truth their movement gained much of its momentum from Washington’s subtle promotion of what they think of as their own agenda. Before the major American rights groups were created, Washington’s national security managers had been discussing the desirability of a national organization to offset the “foreign” influence of the London-based Amnesty International. Before human rights leaders began advocating for extending the laws of war to outlaw abuses by antigovernment guerrilla forces, Washington pursued the same goal as a way of discrediting almost all insurgency movements. And a new humanitarian ethos legitimizing massive interventions—including war—emerged in the 1990s only after Washington had been pushing such an approach for some time. In short, the vocabulary and the arguments of the human rights movement almost all have significant precursors in Washington’s national security concerns.

From Washington’s perspective, the fierce Cold War ideological battles between the “Free World” and its adversaries necessitated lumping together a wide array of radical movements, dissident ideas, and nationalist struggles—all perceived to be inimical to the demands of an America-centered world—in order to dismiss them. But Washington knew all too well that the Free World could hardly restrict its constituents to free countries; it had to align itself with various dictators and brutally repressive regimes. Still, the great “war of ideas” demanded a line be drawn between democratic societies—with free institutions, representative government, and free elections—and those that denied freedom and individual rights.

From the earliest years of the Cold War, Washington predicated its war of ideas on a set of deep divisions: between freedom and equality, reform and revolution, self-interest and collective interests, the free market and state planning, and pluralistic democracy and mass mobilization. American human rights leaders largely, if unknowingly, built on this divide. They usually felt more at ease associating human rights with civil rights and political freedoms, the individual, the market, and pluralistic openness, while seeing the perils in revolution and concentrations of state power. They preferred not to dwell on what might compel populations, as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights warned, “to rebellion against tyranny and oppression”; nor did they acknowledge that it often takes militant mass movements, both violent and nonviolent, to pressure states and powerful interests into acquiescing to programs promoting greater social justice. They considered the struggle for human rights largely apart from peace movements and efforts toward disarmament and the banning of nuclear weaponry, and they took no stand on issues of war and aggression. They mostly viewed resistance movements through the prism of individual rights rather than considering the role of resistance and mass mobilizations in the creation and nourishment of rights.

That Washington has sought to fashion both the conceptual basis and the direction of the human rights movement is hardly surprising—which is not to say that Washington controls the agenda, or that the national security establishment is not constantly competing with Congress, the media, and highly contentious interests abroad. Washington continually has to scramble, searching for ways to refine its strategies and bend ways of thinking to its own ideological ends. Still, it has remained as adept as it was during the Cold War at molding concepts, ideas, and code words. Understanding this process is key to understanding why the human rights movement has developed as it has.

The popular view of a rights-based, democratic American power not only obfuscates the way Washington operates but also advances a rather one-dimensional and parochial vision of human rights. We might more usefully look at human rights as two currents—sometimes contending, sometimes complementary. The first current largely embodies the popular American view, which emphasizes civil and political rights and embraces a moderate, democratic, step-by-step incorporation of human needs into a kind of rights-based legalism. Perhaps such rights are easier to understand in terms of individual freedom: they do more to liberate individuals from the deprivations of caste than of class, freeing them from archaic restraints and traditions but not from economic subjugation. And the outcome is paradoxical. Violations of women’s rights, gay rights, and civil rights of all kinds are increasingly attacked while inequality grows. Diversity and multiculturalism are lauded even as the concentration of wealth and power reaches historic levels. The “laws of war” are applauded and efforts to protect the rights of noncombatants flourish even as wars rage and the larger issues of aggression and occupation are ignored.

The second current has less to do with individual freedom and more to do with basic needs. It is associated with popular mass movements, revolution by populations in desperate straits, and resistance. From this perspective, the human rights movement emerged not only as a response to the savagery of World War II and the Holocaust but, more significantly, out of the movements for independence that broke the grip of European colonialism. Central to the second current are challenges to corporate power, state repression, foreign occupation, and global economic inequality, as well as the protection of collective means of struggle, from labor unions to revolution. Historically, this current affirms the mass-based challenges that allowed human rights to emerge in the first place. It is the drive for both freedom and equality, so deeply embedded in diverse revolutionary traditions and popular struggles for emancipation and justice, that galvanizes this vision of human rights. Today, this current is far more prevalent outside the dominant Western spheres of power.

The first current tends to speak in terms of victims and perpetrators. The second judges a society by how well it treats the poor and the weak. It challenges power by asking why, in large areas of the world where civil liberties and the “rule of law” do hold sway, so little is done to meet the most basic economic, medical, and educational needs of the populace. The second current, then, is less about infusing rights into preexisting structures of power than about fundamentally altering how power works; it is more about transforming the institutional apparatus and the military basis of political power than about invoking rights to control it.

There have been laudable, if infrequent, efforts to honor both currents together. Martin Luther King Jr., for example, fiercely opposed the Vietnam War, insisting that the civil rights and peace movements needed each other to bring about a better world. But there has been little subsequent support for such a merger either in Washington or in the human rights movement. Instead, the prevailing individual-freedom view of human rights has repeatedly been invoked to condemn the “dark underside” of revolution, the corruptions of unchecked state power, the lip service to equality paid by hypocritical leaders busily suppressing freedom—but not to condemn aggression or crimes against peace.

For most human rights leaders today, the long travails of decolonialization and revolution and the search for alternatives to market-driven economic development represent little more than the backwaters of old Cold War battles that were hardly about rights at all. One looks almost in vain for accounts that show how Western power long subordinated the development of the Southern Hemisphere to its own needs and desires, how challenges in the non-Western world propelled the development of human rights laws and ideas, and how mass mobilizations broke the Gordian knot of colonialism and liberalism. Nor do human rights textbooks devote many pages to the great mass movements—not even the civil rights movement in the United States or the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa.5 The major studies of human rights law spend their time instead debating how to enforce UN pronouncements and covenants. The language of law dominates the discussion. But law is the language of institutions, courts, and politicians. The teachings of Mohandas Gandhi and King and the language of impassioned justice are notably absent.

The movement’s deep uneasiness with all forms of radical and revolutionary social change was already evident in 1961, when the newly founded Amnesty International pronounced that no prisoners who advocated violence could be considered prisoners of conscience: thus no revolutionaries—not Nelson Mandela in South Africa, nor even the Berrigan brothers (who had destroyed draft-board records) in the United States. The movement has generally criticized revolutions and decolonializing rebellions as human rights travesties. No insurgency, including those in Vietnam and El Salvador, has escaped its censure for the killing of innocent civilians and the use of terror. No state redistributions of wealth and power have failed to rack up human rights violations; the Chinese Revolution is regarded as one huge atrocity. The Iranian Revolution is attacked as little more than a precursor to further repression. The upheavals of decolonialization are blamed for having opened the way to repressive authoritarian states.

Meanwhile, the virulent hostility of the United States in all these situations is either ignored in human rights reports or else dismissed as irrelevant to judging the violations. The black book of Communism is long and richly illustrated, and the crimes of the new human rights abusers are quickly added in the appendices. But where, we might ask, is the corresponding black book of anticommunism, of United States–backed “nation building” and “counterinsurgency,” with their countless human rights violations, of invocations of the “rule of law” used to legitimize such systemic injustices as wars, occupations, and the economic violence of the marketplace?

None of the movement’s uneasiness with violence and radical struggle translates into a commitment to nonviolence or pacifism. The conventional conception of human rights accepts certain kinds of controlled violence, “justified violence,”6 “proportionality” in warfare, and the legalization of some forms of violence against others. It seeks to moderate war by protecting civilian noncombatants, regulating occupations and counterinsurgency campaigns, and controlling the excesses of governments and resistance movements alike. In other words, the idea is to impose the laws of war, not to outlaw war. Worthwhile as this undertaking may be, it tends to deflect attention from the larger truth that wars, occupations, and aggressive interventions are responsible for much of the violence in the world today. For there is only a thin line between advocating for the laws an occupying power should follow and tacitly legitimizing an occupation by lauding the rights-based methods that sustain it. It is bad enough to legalize some forms of violence with the “laws of war” while ignoring the larger underlying issue of aggression. It is still worse to accept some forms of state violence while outlawing almost all forms of nonstate violence that arise in reaction to it.

Today we look with perplexity at how slavery could coexist with the belief that all men are created equal, how liberalism could rise hand in hand with colonialism and brutal forms of exploitation, how calls for freedom could ignore women’s rights, how the antislavery movement in England could coincide with the Opium Wars against China, and how democracies could fight colonial wars. We like to think these contradictions reflected incomplete developments. Indeed they did. But in various ways such blindness remains with us, a reminder of how tightly interwoven the competing and sometimes conflicting claims of human rights always are.

If we really begin to contend with the contradictions posed by these two currents, we will understand why later generations may look back on our present vision of human rights with the same perplexity. For the rise of the American human rights movement since the 1970s has coincided with an unprecedented increase in inequality, with brutal wars of occupation, and with a determination to establish American preeminence via the greatest concentration of military power in history. In the future, the downplaying of the issues of aggression and crimes against peace may not go unnoticed, for it fits with the character of Washington’s power and its half-century-long war of ideas.

The world is changing profoundly. Yet the tectonic shifts in global power now under way have barely registered on either the Obama administration or human rights leaders. But as the old world gives way, it is urgent that we rethink the meaning of human rights. And nothing presents a greater hurdle to this task than the human rights community’s close if often unwitting links to Washington. Without such a reexamination, the human rights movement may well continue to serve Washington’s ideological needs. In the end, the movement must decide: Can it find a way to truly confront the abusive operations of wealth and power in all their many forms? Or will it consent to being a weapon of privileged power seeking to protect its interests—and its conscience?

Copyright © 2010 by James Peck