Excerpt

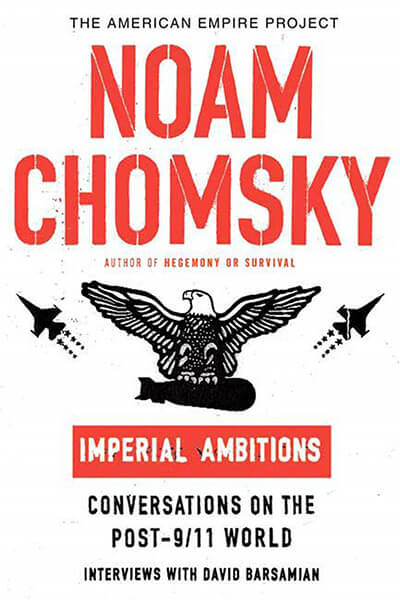

Imperial Ambitions

Conversations on the Post-9/11 World

by Noam Chomsky

Excerpt

Imperial Ambitions

Conversations on the Post-9/11 World

by Noam Chomsky

One Imperial Ambitions

CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS (MARCH 22, 2003)

What are the regional implications of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq? I think not only the region but the world in general correctly perceives the U.S. invasion as a test case, an effort to establish a new norm for the use of military force. This new norm was articulated in general terms by the White House in September 2002 when it announced the new National Security Strategy of the United States of America.1 The report proposed a somewhat novel and unusually extreme doctrine on the use of force in the world, and it’s not accidental that the drumbeat for war in Iraq coincided with the report’s release. The new doctrine was not one of preemptive war, which arguably falls within some stretched interpretation of the UN Charter, but rather a doctrine that doesn’t be gin to have any grounds in international law, namely, preventive war. That is, the United States will rule the world by force, and if there is any challenge to its domination whether it is perceived in the distance, invented, imagined, or whatever—then the United States will have the right to destroy that challenge before it becomes a threat. That’s preventive war, not preemptive war. To establish a new norm, you have to do something. Of course, not every state has the capacity to create what is called a new norm. So if India invades Pakistan to put an end to monstrous atrocities, that’s not a norm. But if the United States bombs Serbia on dubious grounds, that’s a norm. That’s what power means. The easiest way to establish a new norm, such as the right of preventive war, is to select a completely defense less target, which can be easily overwhelmed by the most massive military force in human history. However, in order to do that credibly, at least in the eyes of your own population, you have to frighten people. So the defense less target has to be characterized as an awesome threat to survival that was responsible for September 11 and is about to attack us again, and so on. And this was indeed done in the case of Iraq. In a really spectacular propaganda achievement, which will no doubt go down in his tory, Washington undertook a massive effort to convince Americans, alone in the world, that Saddam Hussein was not only a monster but also a threat to our existence. And it substantially succeeded. Half the U.S. population believes that Saddam Hussein was “personally involved” in the September 11, 2001, attacks.2 So all this falls together. The doctrine is pronounced, the norm is established in a very easy case, the population is driven into a panic and, alone in the world, believes the fantastic threats to its existence, and is therefore willing to support military force in self-defense. And if you believe all of this, then it really is self-defense to invade Iraq, even though in reality the war is a textbook ex ample of aggression, with the purpose of extending the scope for further aggression. Once the easy case is handled, you can move on to harder cases. Much of the world is overwhelmingly opposed to the war because they see that this is not just about an attack on Iraq. Many people correctly perceive it exactly the way it’s intended, as a firm statement that you had better watch out, you could be next. That’s why the United States is now regarded as the greatest threat to peace in the world by a large number of people, probably the vast majority of the population of the world. George Bush has succeeded within a year in converting the United States to a country that is greatly feared, disliked, and even hated.3 At the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in February 2003, you described Bush and the people around him as “radical nationalists” engaging in “imperial violence.”4 Is this regime in Washington, D.C., substantively different from previous ones? It is useful to have some historical perspective, so let’s go to the opposite end of the political spectrum, about as far as you can get, the Kennedy liberals. In 1963, they announced a doctrine which is not very different from Bush’s National Security Strategy. Dean Acheson, a respected elder statesman and a senior adviser to the Kennedy administration, delivered a lecture to the American Society of International Law in which he stated that no “legal issue” arises if the United States responds to any challenge to its “power, position, and prestige.”5 The timing of his statement is quite significant. He made it shortly after the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, which virtually drove the world to the edge of nuclear war. The Cuban missile crisis was largely a result of a major campaign of international terrorism aimed at overthrowing Castro—what’s now called regime change, which spurred Cuba to bring in Russian missiles as a defensive measure. Acheson argued that the United States had the right of preventive war against a mere challenge to our position and prestige, not even a threat to our existence. His word ing, in fact, is even more extreme than that of the Bush doctrine. On the other hand, to put it in perspective, this was a proclamation by Dean Acheson to the American Society of International Law; it wasn’t an official statement of policy. The National Security Strategy document is a formal statement of policy, not just a statement by a high official, and it is unusual in its brazenness. A slogan that we have all heard at peace rallies is “No Blood for Oil.” The whole issue of oil is often referred to as the driving force behind the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq. How central is oil to U.S. strategy? It’s undoubtedly central. I don’t think any sane person doubts that. The Gulf region has been the main energy producing region of the world since the Second World War and is expected to be so for at least another generation. The Persian Gulf is a huge source of strategic power and material wealth. And Iraq is absolutely central to it. Iraq has the second largest oil reserves in the world, and Iraqi oil is very easily accessible and cheap. If you control Iraq, you are in a very strong position to determine the price and production levels (not too high, not too low) to undermine OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries), and to throw your weight around throughout the world. This has nothing in particular to do with access to the oil for import into the United States. It’s about control of the oil. If Iraq were somewhere in central Africa, it wouldn’t be chosen as a test case for the new doctrine of force, though this doesn’t account for the specific timing of the current Iraq operation, because control over Middle East oil is a constant concern. A 1945 State Department document on Saudi Arabian oil calls it “a stupendous source of strategic power, and one of the greatest material prizes in world history.”6 The United States imports quite a bit of its oil, about 15 percent, from Venezuela.7 It also imports oil from Colombia and Nigeria. All three of these states are, from Washington’s perspective, somewhat problematic right now, with Hugo Chavez in control in Venezuela, literally civil war in Colombia, and uprisings and strikes in Nigeria. What do you think about all of those factors? All of this is very pertinent, and the regions you mention are where the United States actually intends to have access. In the Middle East, the United States wants control. But, at least according to intelligence projections, Washington intends to rely on what they regard as more stable Atlantic Basin resources, which means West Africa and the Western Hemisphere, areas that are more fully under U.S. control than is the Middle East, a difficult region. So disruption of one kind or another in those areas is a significant threat, and therefore another episode like Iraq is very likely, especially if the occupation works the way the civilian planners at the Pentagon hope. If it’s an easy victory, with not too much fighting, and Washington can establish a new regime that it will call “democratic,” they will be emboldened to undertake the next intervention. You can think of several possibilities. One of them is the Andean region. The U.S. military has bases and soldiers all around the Andes now. Colombia and Venezuela, especially Venezuela, are both substantial oil producers, and there is more oil in Ecuador and Brazil. Another possibility is Iran. Speaking of Iran, the Bush administration was advised by none other than, as Bush called him, the “man of peace,” Ariel Sharon, to go after Iran “the day after” the United States finished with Iraq.8 What about Iran, a designated “axis of evil” state and also a country that has significant oil reserves? As far as Israel is concerned, Iraq has never been much of an issue. They consider it a kind of pushover. But Iran is a different story. Iran is a much more serious military and economic force. And for years Israel has been pressing the United States to take on Iran. Iran is too big for Israel to attack, so they want the big boys to do it. And it’s quite likely that this war may already be under way. A year ago, more than 10 percent of the Israeli air force was reported to be permanently based in eastern Turkey—at the huge U.S. military base there—and flying reconnaissance over the Iranian border. In addition, there are credible reports that the United States, Turkey, and Is rael are attempting to stir up Azeri nationalist forces in northern Iran.9 That is, an axis of U.S.-Turkish-Israeli power in the region opposed to Iran could ultimately lead to the split-up of Iran and maybe even to military at tack, although a military attack will happen only if it’s taken for granted that Iran would be basically defense less. They’re not going to invade anyone who they think can fight back. With U.S. military forces in Afghanistan and in Iraq, as well as bases in Turkey, Iran is surrounded. The United States also has troops and bases throughout Central Asia to the north. Won’t this encourage Iran to develop nuclear weapons, if they don’t already have them, in self-defense? Very likely. And the little serious evidence we have indicates that the Israeli bombing of Iraq’s Osirak reactor in 1981 probably stimulated and may have initiated the Iraqi nuclear weapons development program. But weren’t they already engaged in it? They were engaged in building a nuclear plant, but no body knew its capacity. It was investigated on the ground after the bombing by a well-known nuclear physicist from Harvard, Richard Wilson. I believe he was head of Harvard’s physics department at the time. Wilson published his analysis in a leading scientific journal, Nature.10 He’s an expert on this topic, and, according to Wilson, Osirak was a power plant. Other Iraqi exile sources have indicated that nothing much was going on; the Iraqis were toying with the idea of nuclear weapons before, but it was the bombing of Osirak that stimulated the nuclear weapons program.11 You can’t prove this, but that’s what the evidence suggests. What does the Iraq war and occupation mean for the Palestinians? That’s interesting to think about. One of the rules of journalism is that when you mention George Bush’s name in an article, the headline has to speak of his “vision” and the article has to talk about his “dreams.” Maybe there will be a photograph of him peering into the distance, right next to the article. It’s become a journalistic convention. A lead story in the Wall Street Journal yesterday, had the words vision and dream about ten times.12 One of George Bush’s dreams is to establish a Palestinian state somewhere, sometime, in some unspecified place—maybe in the Saudi desert. And we are supposed to praise that as a magnificent vision. But all this talk of Bush’s vision and dream of a Palestinian state ignores completely that the United States would have to stop undermining the long-term efforts of the rest of the world, virtually without exception, to create some kind of a viable political settlement. For the last twenty-five to thirty years, the U.S. has been blocking any such settlement. The Bush administration has gone even further than others in blocking a solution, sometimes in such extreme ways that they weren’t even reported. For example, in December 2002, the Bush administration reversed U.S. policy on Jerusalem. At least in principle, the United States had previously gone along with the 1968 Security Council resolution ordering Israel to revoke its annexation and occupation and settlement policies in East Jerusalem. But the Bush administration reversed that policy.13 That’s just one of many measures intended to undermine the possibility of any meaningful political settlement. In mid-March 2002, Bush made what was called his first major pronouncement on the Middle East. The head lines described this as the first significant statement in years, and so on. If you read the speech, it was boiler plate, except for one sentence. That one sentence, if you take a look at it closely, said, “As progress is made toward peace, settlement activity in the occupied territories must end.”14 What does that mean? That means until the peace process reaches a point that Bush endorses, which could be indefinitely far in the future, Israel should continue to build settlements. That’s also a change in policy. Up until now, officially at least, the United States has been opposed to expansion of the illegal settlement programs that make a political solution impossible. But now Bush is saying the opposite: Go on and settle. We’ll keep paying for it, until we decide that somehow the peace process has reached an adequate point. This represents a significant change toward more aggression, undermining of international law, and undermining of the possibilities of peace. You’ve described the level of public protest and resistance to the Iraq war as “unprecedented.”15 Never before has there been so much opposition before a war began. Where is that resistance going in the United States and internationally? I don’t know any way to predict human affairs. It will go the way people decide it will go. There are many possibilities. It should intensify. The tasks are now much greater and more serious than they were before. On the other hand, it’s harder. It’s just psychologically easier to organize to oppose a military attack than it is to oppose a long-standing program of imperial ambition, of which this attack is one phase, with others to come. That takes more thought, more dedication, more long-term engagement. It’s the difference between deciding, I’m going out to a demonstration tomorrow and then back home, and deciding, I’m in this for the long haul. Those are choices people have to make. The same was true for people in the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and in every other movement. What about threats to and intimidation of dissidents here inside the United States, including random roundups of immigrants and Green Card holders, and citizens, for that matter? We definitely have to be concerned. The current government has claimed rights that go beyond any precedents, including even the right to arrest citizens, hold them in detention without access to their family or lawyers, and do so indefinitely, without charges.16 And immigrants and other vulnerable people should certainly be cautious. On the other hand, for people like us, citizens with any privileges, though there are threats, they are so slight as compared with what people face in most of the world that it’s hard to get very upset about them. I’ve just come back from a couple of trips to Turkey and Colombia, and compared with the threats that people face there, we’re living in heaven. People in Colombia and Turkey worry about state repression, of course, but they don’t let it stop them. Do you see Europe or East Asia emerging as counterforces to U.S. power at some point? There is no doubt that Europe and Asia are economic forces on par with North America, roughly, and have their own interests, which are not simply to follow U.S. orders. Of course, they’re all tightly linked. So, for example, the corporate sectors in Europe, the United States, and most of Asia are connected in all kinds of ways and have common interests; but they also have separate interests, which is the cause of problems that go way back, especially with Europe. The United States has always had an ambivalent attitude toward Europe. It wanted Europe to be unified, so it could serve as a more efficient market for U.S. corporations, offering great advantages of scale; but it was always concerned about the threat that Europe might move off in another direction. Many of the issues about accession of the eastern countries to the European Union (EU) are re lated to this. The United States is strongly in favor of this accession process, because it is hoping that these countries will be more susceptible to U.S. influence and will be able to undermine the core of Europe, which is France and Germany, big industrial countries that could move in a somewhat more independent direction. Also in the background is a long-standing U.S. hatred of the European social system, which provides decent wages, working conditions, and benefits. The United States doesn’t want that model to exist, because it’s a dangerous one. People may get funny ideas. And it’s understood that the accession of eastern European coun tries, with economies based on low wages and repression of labor, may help undermine the social standards in western Europe. That would be a big benefit for the United States. With the U.S. economy deteriorating and with the prospect of more layoffs on the horizon, how is the Bush administration going to maintain what some are calling a garrison state, engaged in permanent war and the occupation of numerous countries? How are they going to pull it off? They only have to pull it off for about another six years. By that time, they hope to have institutionalized a series of highly reactionary programs within the United States. They will have left the economy in a very serious state, with huge deficits, pretty much the way they did in the 1980s. And then it will be somebody else’s problem. Meanwhile, they will have undermined social programs and diminished democracy—which of course they hate by transferring decisions out of the public arena into private hands. Internally, the legacy they leave will be painful and hard, but only for the majority of the population. The people they’re concerned about are go ing to be making out like bandits, very much like during the Reagan years. Many of the same people are in power now, after all. And internationally, they hope that they will have institutionalized the doctrines of imperial domination through force and preventive wars of choice. In military force and spending, the United States probably exceeds the rest of the world combined, and is now moving in extremely dangerous directions, including the militarization of space. And they assume, I suppose, that no matter what happens to the economy, U.S. military force will be so overwhelming that people will just have to do what they say. What do you say to the peace activists in the United States who labored to prevent the invasion of Iraq and who now are feeling a sense of anger, and despair, that their government has done this? That they should be realistic. Consider abolitionism. How long did the struggle go on before the abolitionist movement made any progress? If you give up every time you don’t achieve the immediate gain you want, you’re just guaranteeing that the worst is going to happen. These are long, hard struggles. And, in fact, what has happened in the last couple of months should be seenquite positively. The basis was created for expansion anddevelopment of a peace and justice movement that can goon to much harder tasks. And that’s the way these thingsare. You can’t expect an easy victory after one protestmarch. Copyright © 2005 by Noam Chomsky