Excerpt

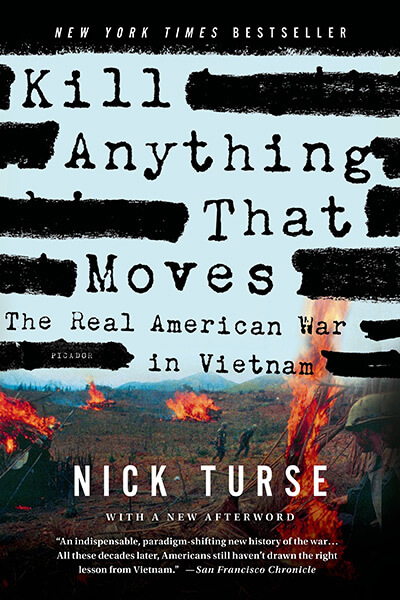

Kill Anything That Moves

The Real American War in Vietnam

by Nick Turse

Excerpt

Kill Anything That Moves

The Real American War in Vietnam

by Nick Turse

Introduction An Operation, Not an Aberration

On January 21, 1971, a Vietnam veteran named Charles McDuff wrote a letter to President Richard Nixon to voice his disgust with the American war in Southeast Asia. McDuff had witnessed multiple cases of Vietnamese civilians being abused and killed by American soldiers and their allies, and he had found the U.S. military justice system to be woefully ineffective in punishing wrongdoers. “Maybe your advisors have not clued you in,” he told the president, “but the atrocities that were committed in Mylai are eclipsed by similar American actions throughout the country.” His three-page handwritten missive concluded with an impassioned plea to Nixon to end American participation in the war.1 The White House forwarded the note to the Department of Defense for a reply, and within a few weeks Major General Franklin Davis Jr., the army’s director of military personnel policies, wrote back to McDuff. It was “indeed unfortunate,” said Davis, “that some incidents occur within combat zones.” He then shifted the burden of responsibility for what had happened firmly back onto the veteran. “I presume,” he wrote, “that you promptly reported such actions to the proper authorities.” Other than a paragraph of information on how to contact the U.S. Army criminal investigators, the reply was only four sentences long and included a matter-of-fact reassurance: “The United States Army has never condoned wanton killing or disregard for human life.”2 This was, and remains, the American military’s official position. In many ways, it remains the popular understanding in the United States as a whole. Today, histories of the Vietnam War regularly discuss war crimes or civilian suffering only in the context of a single incident: the My Lai massacre cited by McDuff. Even as that one event has become the subject of numerous books and articles, all the other atrocities perpetrated by U.S. soldiers have essentially vanished from popular memory. The visceral horror of what happened at My Lai is undeniable. On the evening of March 15, 1968, members of the Americal Division’s Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry, were briefed by their commanding officer, Captain Ernest Medina, on a planned operation the next day in an area they knew as “Pinkville.” As unit member Harry Stanley recalled, Medina “ordered us to ‘kill everything in the village.’ ” Infantryman Salvatore LaMartina remembered Medina’s words only slightly differently: they were to “kill everything that breathed.” What stuck in artillery forward observer James Flynn’s mind was a question one of the other soldiers asked: “Are we supposed to kill women and children?” And Medina’s reply: “Kill everything that moves.”3 The next morning, the troops clambered aboard helicopters and were airlifted into what they thought would be a “hot LZ”—a landing zone where they’d be under hostile fire. As it happened, though, instead of finding Vietnamese adversaries spoiling for a fight, the Americans entering My Lai encountered only civilians: women, children, and old men. Many were still cooking their breakfast rice. Nevertheless, Medina’s orders were followed to a T. Soldiers of Charlie Company killed. They killed everything. They killed everything that moved. Advancing in small squads, the men of the unit shot chickens as they scurried about, pigs as they bolted, and cows and water buffalo lowing among the thatch-roofed houses. They gunned down old men sitting in their homes and children as they ran for cover. They tossed grenades into homes without even bothering to look inside. An officer grabbed a woman by the hair and shot her point-blank with a pistol. A woman who came out of her home with a baby in her arms was shot down on the spot. As the tiny child hit the ground, another GI opened up on the infant with his M-16 automatic rifle. Over four hours, members of Charlie Company methodically slaughtered more than five hundred unarmed victims, killing some in ones and twos, others in small groups, and collecting many more in a drainage ditch that would become an infamous killing ground. They faced no opposition. They even took a quiet break to eat lunch in the midst of the carnage. Along the way, they also raped women and young girls, mutilated the dead, systematically burned homes, and fouled the area’s drinking water.4 There were scores of witnesses on the ground and still more overhead, American officers and helicopter crewmen perfectly capable of seeing the growing piles of civilian bodies. Yet when the military released the first news of the assault, it was portrayed as a victory over a formidable enemy force, a legitimate battle in which 128 enemy troops were killed without the loss of a single American life.5 In a routine congratulatory telegram, General William Westmoreland, the commander of U.S. forces in Vietnam, lauded the “heavy blows” inflicted on the enemy. His protégé, the commander of the Americal Division, added a special note praising Charlie Company’s “aggressiveness.”6 Despite communiqués, radio reports, and English-language accounts released by the Vietnamese revolutionary forces, the My Lai massacre would remain, to the outside world, an American victory for more than a year. And the truth might have remained hidden forever if not for the perseverance of a single Vietnam veteran named Ron Ridenhour. The twenty-two-year-old Ridenhour had not been among the hundred American troops at My Lai, though he had seen civilians murdered elsewhere in Vietnam; instead, he heard about the slaughter from other soldiers who had been in Pinkville that day. Unnerved, Ridenhour took the unprecedented step of carefully gathering testimony from multiple American eyewitnesses. Then, upon returning to the United States after his yearlong tour of duty, he committed himself to doing whatever was necessary to expose the incident to public scrutiny.7 Ridenhour’s efforts were helped by the painstaking investigative reporting of Seymour Hersh, who published newspaper articles about the massacre; by the appearance in Life magazine of grisly full-color images that army photographer Ron Haeberle captured in My Lai as the slaughter was unfolding; and by a confessional interview that a soldier from Charlie Company gave to CBS News. The Pentagon, for its part, consistently fought to minimize what had happened, claiming that reports by Vietnamese survivors were wildly exaggerated. At the same time, the military focused its attention on the lowest-ranking officer who could conceivably shoulder the blame for such a nightmare: Charlie Company’s Lieutenant William Calley.8 An army inquiry into the killings eventually determined that thirty individuals were involved in criminal misconduct during the massacre or its cover-up. Twenty-eight of them were officers, including two generals, and the inquiry concluded they had committed a total of 224 serious offenses.9 But only Calley was ever convicted of any wrongdoing. He was sentenced to life in prison for the premeditated murder of twenty-two civilians, but President Nixon freed him from prison and allowed him to remain under house arrest. He was eventually paroled after serving just forty months, most of it in the comfort of his own quarters.10 The public response generally followed the official one. Twenty-five years later, Ridenhour would sum it up this way.

At the end of it, if you ask people what happened at My Lai, they would say: “Oh yeah, isn’t that where Lieutenant Calley went crazy and killed all those people?” No, that was not what happened. Lieutenant Calley was one of the people who went crazy and killed a lot of people at My Lai, but this was an operation, not an aberration.11

Looking back, it’s clear that the real aberration was the unprecedented and unparalleled investigation and exposure of My Lai. No other American atrocity committed during the war—and there were so many—was ever afforded anything approaching the same attention. Most, of course, weren’t photographed, and many were not documented in any way. The great majority were never known outside the offending unit, and most investigations that did result were closed, quashed, or abandoned. Even on the rare occasions when the allegations were seriously investigated within the military, the reports were soon buried in classified files without ever seeing the light of day.12 Whistle-blowers within the ranks or recently out of the army were threatened, intimidated, smeared, or—if they were lucky—simply marginalized and ignored. Until the My Lai revelations became front-page news, atrocity stories were routinely disregarded by American journalists or excised by stateside editors. The fate of civilians in rural South Vietnam did not merit much examination; even the articles that did mention the killing of noncombatants generally did so merely in passing, without any indication that the acts described might be war crimes.13 Vietnamese revolutionary sources, for their part, detailed hundreds of massacres and large-scale operations that resulted in thousands of civilian deaths, but those reports were dismissed out of hand as communist propaganda.14 And then, in a stunning reversal, almost immediately after the exposure of the My Lai massacre, war crime allegations became old hat—so commonplace as to be barely worth mentioning or looking into. In leaflets, pamphlets, small-press books, and “underground” newspapers, the growing American antiwar movement repeatedly pointed out that U.S. troops were committing atrocities on a regular basis. But what had been previously brushed aside as propaganda and leftist kookery suddenly started to be disregarded as yawn-worthy common knowledge, with little but the My Lai massacre in between.15 Such impulses only grew stronger in the years of the “culture wars,” when the Republican Party and an emboldened right wing rose to power. Until Ronald Reagan’s presidency, the Vietnam War was generally seen as an American defeat, but even before taking office Reagan began rebranding the conflict as “a noble cause.” In the same spirit, scholars and veterans began, with significant success, to recast the war in rosier terms.16 Even in the early years of the twenty-first century, as newspapers and magazines published exposés of long-hidden U.S. atrocities, apologist historians continued to ignore much of the evidence, portraying American war crimes as no more than isolated incidents.17 But the stunning scale of civilian suffering in Vietnam is far beyond anything that can be explained as merely the work of some “bad apples,” however numerous. Murder, torture, rape, abuse, forced displacement, home burnings, specious arrests, imprisonment without due process—such occurrences were virtually a daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam. And as Ridenhour put it, they were no aberration. Rather, they were the inevitable outcome of deliberate policies, dictated at the highest levels of the military. The first official American combat troops arrived in Vietnam in 1965, but the roots of the conflict go back many decades earlier. In the nineteenth century, France expanded its colonial empire by taking control of Vietnam as well as neighboring Cambodia and Laos, rechristening the entire region as French Indochina. French rubber production in Vietnam yielded such riches for the colonizers that the latex oozing from rubber trees became known as “white gold.” The ill-paid Vietnamese workers, laboring on the plantations in harsh conditions, called it by a different name: “white blood.”18 By the early twentieth century, anger at the French had developed into a nationalist movement for independence. Its leaders found inspiration in communism, specifically the example of Russian Bolshevism and Lenin’s call for national revolutions in the colonial world. During World War II, when Vietnam was occupied by the imperial Japanese, the country’s main anticolonial organization—officially called the League for the Independence of Vietnam, but far better known as the Viet Minh—launched a guerrilla war against the Japanese forces and the French administrators running the country. Under the leadership of the charismatic Ho Chi Minh, the Vietnamese guerrillas aided the American war effort. In return they received arms, training, and support from the U.S. Office of Strategic Services, a forerunner of the Central Intelligence Agency. In 1945, with the Japanese defeated, Ho proclaimed Vietnam’s independence, using the words of the U.S. Declaration of Independence as his template. “All men are created equal,” he told a crowd of half a million Vietnamese in Hanoi. “The Creator has given us certain inviolable rights: the right to life, the right to be free, and the right to achieve happiness.” As a young man Ho had spent some years living in the West, reportedly including stretches in Boston and New York City, and he hoped to obtain American support for his vision of a free Vietnam. In the aftermath of World War II, however, the United States was focused on rebuilding and strengthening a devastated Europe, as the Cold War increasingly gripped the continent. The Americans saw France as a strong ally against any Soviet designs on Western Europe and thus had little interest in sanctioning a communist-led independence movement in a former French colony. Instead, U.S. ships helped transport French troops to Vietnam, and the administration of President Harry Truman threw its support behind a French reconquest of Indochina. Soon, the United States was dispatching equipment and even military advisers to Vietnam. By 1953, it was shouldering nearly 80 percent of the bill for an ever more bitter war against the Viet Minh.19 The conflict progressed from guerrilla warfare to a conventional military campaign, and in 1954 a Gallic garrison at the well-fortified base of Dien Bien Phu was pounded into surrender by Viet Minh forces under General Vo Nguyen Giap. The French had had enough. At an international peace conference in Geneva, they agreed to a temporary separation of Vietnam into two placeholder regions, the north and the south, which were to be rejoined as one nation following a reunification election in 1956. That election never took place. Fearing that Ho Chi Minh, now the head of the communist Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north, was sure to sweep any nationwide vote, the United States picked up where its French partners had left off. It promptly launched efforts to thwart reunification by arming its allies in the southern part of the country. In this way, it fostered the creation of what eventually became the Republic of Vietnam, led by a Catholic autocrat named Ngo Dinh Diem. From the 1950s on, the United States would support an ever more corrupt and repressive state in South Vietnam while steadily expanding its presence in Southeast Asia. When President John Kennedy took office there were around 800 U.S. military personnel in South Vietnam. That number increased to 3,000 in 1961, and to more than 11,000 the following year. Officially listed as advisers involved in the training of the South Vietnamese army, the Americans increasingly took part in combat operations against southern guerrillas—both communist and noncommunist—who were now waging war to unify the country.20 After Kennedy’s assassination, President Lyndon Johnson repeatedly escalated the war with bombing raids on North Vietnam, and unleashed an ever more furious onslaught on the South. In 1965 the fiction of “advisers” was finally dropped, and the American War, as it is known in Vietnam, began in earnest. In a televised speech, Johnson insisted that the United States was not inserting itself into a faraway civil war but taking steps to contain a communist menace. The war, he said, was “guided by North Vietnam . . . Its goal is to conquer the South, to defeat American power, and to extend the Asiatic dominion of communism.”21 To counter this, the United States turned huge swaths of the South Vietnamese countryside—where most of South Vietnam’s population lived—into battered battlegrounds. At the peak of U.S. operations, in 1969, the war involved more than 540,000 American troops in Vietnam, plus some 100,000 to 200,000 U.S. troops participating in the effort from outside the country. They were also aided by numerous CIA operatives, civilian advisers, mercenaries, civilian contractors, and armed members of the allied “Free World Forces”—South Korean, Australian, New Zealand, Thai, Filipino, and other foreign troops.22 Over the entire course of the conflict, the United States would deploy more than 3 million soldiers, marines, airmen, and sailors to Southeast Asia.23 (Fighting alongside them were hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese troops: the Army of the Republic of Vietnam would balloon to a force of nearly 1 million before the end of the war, to say nothing of South Vietnam’s air force, navy, marine corps, and national police.) Officially, the American military effort lasted until early 1973, when a cease-fire was signed and U.S. combat forces were formally withdrawn from the country, though American aid and other support would continue to flow into the Republic of Vietnam until Saigon fell to the revolutionary forces in 1975. From the U.S. perspective, the enemy was composed of two distinct groups: members of the North Vietnamese army and indigenous South Vietnamese fighters loyal to the National Liberation Front, the revolutionary organization that succeeded the Viet Minh and opposed the U.S.-allied Saigon government. The NLF’s combatants, officially known as the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF), included guerrillas in peasant clothing as well as uniformed troops organized into professionalized units. The U.S. Information Service invented the moniker “Viet Cong”—that is, Vietnamese Communists—as a derogatory term that covered anyone fighting on the side of the NLF, though many of the guerrillas themselves were driven more by nationalism than by communist ideology. American soldiers, in turn, often shortened this label to “the Cong” or “VC,” or, owing to the military’s phonetic Alpha-Bravo-Charlie alphabet, to “Victor Charlie” or simply “Charlie.”24 By 1968 the U.S. forces and their allies in the South were opposed by an estimated 50,000 North Vietnamese troops plus 60,000 uniformed PLAF soldiers, while the revolutionaries’ paramilitary forces—part-time, local guerrillas—likely reached into the hundreds of thousands.25 Americans often made hard-and-fast distinctions between the well-armed, green- or khaki-uniformed North Vietnamese troops with their fabric-covered, pressed-cardboard pith-style helmets; the khaki-clad main force PLAF soldiers, with their floppy cloth “boonie hats”; and the lightly armed, “black pajama”–clad guerrillas (all of whom actually wore a wide variety of types and colors of clothing depending on the time and place). In reality, though, they were very hard to disentangle, since North Vietnamese troops reinforced PLAF units, “local” VC fought in tandem with “hard-core” professionalized PLAF troops, and part-time farmer-fighters assisted uniformed North Vietnamese forces. The plethora of designations and the often hazy distinctions between them underscore the fact that the Americans never really grasped who the enemy was. On one hand, they claimed the VC had little popular support and held sway over villages only through terror tactics. On the other, American soldiers who were supposedly engaged in countering communist aggression to protect the South Vietnamese readily killed civilians because they assumed that most villagers either were in league with the enemy or were guerrillas themselves once the sun went down. The United States never wanted to admit that the conflict might be a true “people’s war,” and that Vietnamese were bound to the revolution because they saw it as a fight for their families, their land, and their country. In the villages of South Vietnam, Vietnamese nationalists had long organized themselves to resist foreign domination, and it was no different when the Americans came. By then, the local population was often inextricably joined to the liberation struggle. Lacking advanced technology, financial resources, or significant firepower, America’s Vietnamese enemies maximized assets like concealment, local knowledge, popular support, and something less quantifiable—call it patriotism or nationalism, or perhaps a hope and a dream. Of course, not every Vietnamese villager believed in the revolution or saw it as the best expression of nationalist patriotism. Even villages in revolutionary strongholds were home to some supporters of the Saigon government. And many more farmers simply wanted nothing to do with the conflict or abstract notions like nationalism and communism. They worried mainly about their next rice crop, their animals, their house and children. But bombs and napalm don’t discriminate. As gunships and howitzers ravaged the landscape, as soldiers with M-16 rifles and M-79 grenade launchers swept through the countryside, Vietnamese villagers of every type—supporters of the revolution, sympathizers of the Saigon regime, and those who merely wanted to be left alone—all perished in vast numbers. The war’s casualty figures are staggering indeed. From 1955 to 1975, the United States lost more than 58,000 military personnel in Southeast Asia. Its troops were wounded around 304,000 times, with 153,000 cases serious enough to require hospitalization, and 75,000 veterans left severely disabled.26 While Americans who served in Vietnam paid a grave price, an extremely conservative estimate of Vietnamese deaths found them to be “proportionally 100 times greater than those suffered by the United States.”27 The military forces of the U.S.-allied Republic of Vietnam reportedly lost more than 254,000 killed and more than 783,000 wounded.28 And the casualties of the revolutionary forces were evidently far graver—perhaps 1.7 million, including 1 million killed in battle, plus some 300,000 personnel still “missing” according to the official but incomplete Vietnamese government figures.29 Horrendous as these numbers may be, they pale in comparison to the estimated civilian death toll during the war years. At least 65,000 North Vietnamese civilians were killed, mainly from U.S. air raids.30 No one will ever know the exact number of South Vietnamese civilians killed as a result of the American War. While the U.S. military attempted to quantify almost every other aspect of the conflict—from the number of helicopter sorties flown to the number of propaganda leaflets dispersed—it quite deliberately never conducted a comprehensive study of Vietnamese noncombatant casualties.31 Whatever civilian casualty statistics the United States did tally were generally kept secret, and when released piecemeal they were invariably radical undercounts.32 Yet even the available flawed figures are startling, especially given that the total population of South Vietnam was only about 19 million people. Using fragmentary data and questionable extrapolations that, for instance, relied heavily on hospital data yet all but ignored the immense number of Vietnamese treated by the revolutionary forces (and also failed to take into account the many civilians killed by U.S. forces and claimed as enemies), one Department of Defense statistical analyst came up with a postwar estimate of 1.2 million civilian casualties, including 195,000 killed.33 In 1975, a U.S. Senate subcommittee on refugees and war victims offered an estimate of 1.4 million civilian casualties in South Vietnam, including 415,000 killed.34 Or take the figures proffered by the political scientist Guenter Lewy, the progenitor of a revisionist school of Vietnam War history that invariably shines the best possible light on the U.S. war effort. Even he posits that there were more than 1.1 million South Vietnamese civilian casualties, including almost 250,000 killed, as a result of the conflict.35 In recent years, careful surveys, analyses, and official estimates have consistently pointed toward a significantly higher number of civilian deaths.36 The most sophisticated analysis yet of wartime mortality in Vietnam, a 2008 study by researchers from Harvard Medical School and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation at the University of Washington, suggested that a reasonable estimate might be 3.8 million violent war deaths, combatant and civilian.37 Given the limitations of the study’s methodology, there are good reasons to believe that even this staggering figure may be an underestimate.38 Still, the findings lend credence to an official 1995 Vietnamese government estimate of more than 3 million deaths in total—including 2 million civilian deaths—for the years when the Americans were involved in the conflict.39 The sheer number of civilian war wounded, too, has long been a point of contention. The best numbers currently available, though, begin to give some sense of the suffering. A brief accounting shows 8,000 to 16,000 South Vietnamese paraplegics; 30,000 to 60,000 South Vietnamese left blind; and some 83,000 to 166,000 South Vietnamese amputees.40 As far as the total number of the civilian war wounded goes, Guenter Lewy approaches the question by using a ratio derived from South Vietnamese data on military casualties, which shows 2.65 soldiers seriously wounded for every one killed. Such a proportion is distinctly low when applied to the civilian population; still, even this multiplier, if applied to the Vietnamese government estimate of 2 million civilian dead, yields a figure of 5.3 million civilian wounded, for a total of 7.3 million Vietnamese civilian casualties overall.41 Notably, official South Vietnamese hospital records indicate that approximately one-third of those wounded were women and about one-quarter were children under thirteen years of age.42 What explains these staggering figures? Because the My Lai massacre has entered the popular American consciousness as an exceptional, one-of-a-kind event, the deaths of other civilians during the Vietnam War tend to be vaguely thought of as a matter of mistakes or (to use a phrase that would come into common use after the war) of “collateral damage.” But as I came to see, the indiscriminate killing of South Vietnamese noncombatants—the endless slaughter that wiped out civilians day after day, month after month, year after year throughout the Vietnam War—was neither accidental nor unforeseeable. I stumbled upon the first clues to this hidden history almost by accident, in June 2001, when I was a graduate student researching post-traumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans. One afternoon, I was looking through documents at the U.S. National Archives when a friendly archivist asked me, “Could witnessing war crimes cause post-traumatic stress?” I had no idea at the time that the archives might have any records on Vietnam-era war crimes, so the prospect had never dawned on me. Within an hour or so, though, I held in my hands the yellowing records of the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group, a secret Pentagon task force that had been assembled after the My Lai massacre to ensure that the army would never again be caught off-guard by a major war crimes scandal. To call the records a “treasure trove” feels strange, given the nature of the material. But that’s how the collection struck me then, box after box of criminal investigation reports and day-to-day paperwork long buried away and almost totally forgotten. There were some files as thick as a phonebook, with the most detailed and nightmarish descriptions; other files, paper-thin, hinting at terrible events that had received no follow-up attention; and just about everything in between. As I leafed through them that day, I knew one thing almost instantly: they documented a nightmare war that is essentially missing from our understanding of the Vietnam conflict. The War Crimes Working Group files included more than 300 allegations of massacres, murders, rapes, torture, assaults, mutilations, and other atrocities that were substantiated by army investigators. They detailed the deaths of 137 civilians in mass killings, and 78 smaller-scale attacks in which Vietnamese civilians were killed, wounded, and sexually assaulted. They identified 141 instances in which U.S. troops used fists, sticks, bats, water torture, and electrical torture on noncombatants. The files also contained 500 allegations that weren’t proven at the time—like the murders of scores, perhaps hundreds, of Vietnamese civilians by the 101st Airborne Division’s Tiger Force, which would be confirmed and made public only in 2003. In hundreds of incident summaries and sworn statements in the War Crimes Working Group files, veterans laid bare what had occurred in the backlands of rural Vietnam—the war that Americans back home didn’t see nightly on their televisions or read about over morning coffee. A sergeant told investigators how he had put a bullet, point-blank, into the brain of an unarmed boy after gunning down the youngster’s brother; an army ranger matter-of-factly described slicing the ears off a dead Vietnamese and said that he planned to continue mutilating corpses.43 Other files documented the killing of farmers in their fields and the rape of a child carried out by an interrogator at an army base. Reading case after case—like the incident in which a lieutenant “captured two unarmed and unidentified Vietnamese males, estimated ages 2–3 and 7–8 years . . . and killed them for no reason”—I began to get a sense of the ubiquity of atrocity during the American War.44 In the years that followed, with the War Crimes Working Group documents as an initial guide, I began to track down more information about little-known or never-revealed Vietnam War crimes. I located other investigation files at the National Archives, submitted requests under the Freedom of Information Act, interviewed generals and top civilian officials, and talked to former military war crimes investigators. I also spoke with more than one hundred American veterans across the country, both those who had witnessed atrocities and others who had personally committed terrible acts. From them I learned something of what it was like to be twenty years old, with few life experiences beyond adolescence in a small town or an inner-city neighborhood, and to be suddenly thrust into villages of thatch and bamboo homes that seemed ripped straight from the pages of National Geographic, the paddies around them such a vibrant green that they almost burned the eye. Veteran after veteran told me about days of shattering fatigue and the confusion of contradictory orders, about being placed in situations so alien and unnerving that even with their automatic rifles and grenades they felt scared walking through hamlets of unarmed women and children. Some of the veterans I tried to contact wanted nothing to do with my questions, almost instantaneously slamming down the phone receiver. But most were willing to speak to me, and many even seemed glad to talk to someone who had a sense of the true nature of the war. In homes from Maryland to California, across kitchen tables and in marathon four-hour telephone calls, scores of former soldiers and marines opened up about their experiences. Some had little remorse; an interrogator who’d tortured prisoners, for instance, told me that his actions were merely standard operating procedure. Another veteran, whispering so that his family wouldn’t overhear, adamantly insisted that, though he’d been present at a massacre of civilians, he hadn’t pulled the trigger, no matter what his fellow unit members said. Then there was the veteran who swore that he knew nothing about civilians being killed, only to later recount an incident in which someone in his unit shot an unarmed woman in the back. And yet another former GI ruefully recounted how, walking through a Vietnamese village, he had spun around when a local woman chattered angrily at him (probably complaining about the commotion that the troops were causing) and driven the butt of his rifle into her nose. He remembered walking away, laughing, as blood poured from the woman’s face. Decades later, he could no longer imagine how his nineteen-year-old self had done such a thing, nor could I easily connect this jovial man to that angry adolescent with a brutal streak. My conversations with the veterans gave nuance to my understanding of the war, bringing human emotion to the sometimes dry language of military records, and added context to investigation files that often focused on a single incident. These men also repeatedly showed me just how incomplete the archives I’d come upon really were, even though the files detailed hundreds of atrocity allegations. In one case, for instance, I called a veteran seeking more information about a sexual assault carried out by members of his unit, which I found mentioned in one of the files. He offered me more details about that particular incident but also said that it was no anomaly. Men from his unit had raped numerous other women as well, he told me. But neither those assaults nor the random shootings of farmers by his fellow soldiers had ever been formally investigated. Among the most poignant of the interviews I conducted was with Jamie Henry, a former army medic with whom I eventually forged a friendship. Henry was a whistle-blower in the Ron Ridenhour mold—the type of man that many want to be but few actually are, a courageous veteran who spent several years after his return to America trying to bring to light a series of atrocities committed by his unit. While many others had kept silent, Henry stepped forward and reported the crimes he’d seen, taking significant risks for what he believed was right. He talked to the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command (known as CID), he wrote a detailed article, he spoke out in public again and again. But the army left him to twist in the wind, a lone voice repeatedly recounting apparently uncorroborated tales of shocking violence, while most Americans paid little attention. Until I sought him out and showed him the documents I’d found, Henry had no idea that in the early 1970s military investigators had in fact tracked down and interviewed his fellow unit members, proving his allegations beyond any doubt—and that the army had then hidden away this information, never telling him or anyone else. When he looked over my stacks of photocopies, he was astounded. Over time, following leads from the veterans I’d spoken to and from other sources, I discovered additional long-forgotten court-martial records, investigation files, and related documents in assorted archives and sometimes in private homes across the country. Paging through one of these case files, I found myself virtually inhaling decades-old dust from half a world away. The year was 1970, and a small U.S. Army patrol had set up an ambush in the jungle near the Minh Thanh rubber plantation in Binh Long Province, north of Saigon. Almost immediately the soldiers heard chopping noises, then branches snapping and Vietnamese voices coming toward them. Next, a man broke through the brush—he was in uniform, they would later say, as was the entire group of Vietnamese following behind him. In an instant, the Americans sprang the ambush, setting off two Claymore mines—each sending seven hundred small steel pellets flying more than 150 feet in a lethal sixty-degree arc—and firing an M-60 machine gun. All but one of the Vietnamese in the clearing were killed instantly. The unit’s radioman immediately got on his field telephone and called in ten “enemy KIA”—killed in action. Later, however, something didn’t ring right at headquarters. Despite the claim of ten enemy dead, the Americans had no weapons to show for it. With the My Lai trials garnering headlines back in the United States, the commanding general of the 25th Infantry Division did something unusual: he asked the division’s Office of the Inspector General, whose job it was to probe instances of alleged misconduct, to investigate. The next day, a lieutenant colonel and his team arrived at the site of the ambush, where they found the corpses of five men, three women, and two children scattered on the forest floor. None was wearing enemy uniforms, and civilian identification cards were found on the bodies. The closest thing to a weapon was a piece of paper with “a small drawing of a rifle and of an airplane.” The soldiers who sprang the ambush claimed it was evidence that the dead were enemy fighters, but the lieutenant colonel noted that it looked like “something a child would do.” Similarly, “the makings of booby traps” found on the bodies, and cited by the soldiers as evidence of hostile intent, turned out to be a harmless agricultural tool. As the American investigators photographed the corpses, it was apparent that the Vietnamese had been civilians carrying bags of bamboo shoots and a couple of handfuls of limes—regular people simply trying to eke out an existence in a war-ravaged landscape. The lime gatherers’ deaths were typical of the kind of operation that repeatedly wiped out civilians during the Vietnam War. Most of the time, the noncombatants who died were not herded into a ditch and gunned down as at My Lai. Instead, the full range of the American arsenal—from M-16s and Claymore mines to grenades, bombs, mortars, rockets, napalm, and artillery shells—was unleashed on forested areas, villages, and homes where perfectly ordinary Vietnamese just happened to live and work. As the inspector general’s report concluded in this particular incident, the “Vietnamese victims were innocent civilians loyal to the Republic of Vietnam.” Yet, as so often happened, no disciplinary action of any type was taken against any member of the unit. In fact, their battalion commander stated that the team performed “exactly as he expected them to.” The battalion’s operations officer explained that the civilians had been in an “off-limits” or free-fire zone, one of many swaths of the country where everyone was assumed to be the enemy. Therefore, the soldiers had behaved in accordance with the U.S. military’s directives on the use of lethal force. It made no difference that the lime gatherers happened to live there, as their ancestors undoubtedly had for decades, if not centuries, before them. It made no difference that, as the local province chief of the U.S.-allied South Vietnamese government told the army, “the civilians in the area were poor, uneducated and went wherever they could get food.” The inspector general’s report pointed out that there was no written documentation regarding the establishment of a free-fire zone in the area, noting with bureaucratic understatement that “doubt exists” that the program to warn Vietnamese civilians about off-limits areas was “either effective or thorough.” But that, too, made no difference. As the final investigation report put it, the platoon had operated “within its orders which had been given and/or sanctioned by competent authority . . . The rules of engagement were not violated.”45 Seeking to connect such formal military records with the actual experience of the ordinary Vietnamese people who had lived through these events, I made several trips to Vietnam, making my way to remote rural villages with an interpreter at my side. The jigsaw-puzzle pieces were not always easy to align. In the files of the War Crimes Working Group, for example, I located an exceptionally detailed investigation of a massacre of nearly twenty women and children by a U.S. Army unit in a tiny hamlet in Quang Nam Province on February 8, 1968. It was clear that the ranking officer there had ordered his men to “kill anything that moves,” and that some of the soldiers had obeyed. What was less than clear was exactly where “there” was. With only a general location to go by—fifteen miles west of an old port town known as Hoi An—we embarked on a shoe-leather search. Inquiries with locals led us to An Truong, a small hamlet with a monument to a 1968 massacre. But this particular mass killing took place on January 9, 1968, rather than in February, and was carried out by South Korean forces allied to the Americans rather than by U.S. soldiers themselves. It was not the place we had been looking for. After we explained the situation, one of the residents led us to another village not very far away. It, too, had a memorial—this one commemorating thirty-three locals who died in three separate massacres between 1967 and 1970. However, none of these massacres had taken place on February 8, 1968, either. After interviewing villagers about these atrocities, we asked if they knew of any other mass killings in the area. Yes, they said: not the next hamlet down the road but a little bit beyond it. So on we went. Daylight was rapidly fading when we arrived in that hamlet and found a monument that spelled out the basics of the grim story in spare terms: U.S. troops had killed dozens of Vietnamese there in 1968. Conversations with the farmers made it clear, though, that these Americans were marines, not army soldiers, and the massacre had taken place in August. Such is the nature of investigating war crimes in Vietnam. I’d thought that I was looking for a needle in a haystack; what I found was a veritable haystack of needles. In the United States, meanwhile, the situation in the archives was often frustratingly the opposite. At one point, a Vietnam veteran passed on to me a few pages of documents from an investigation into the killing of civilians by U.S. marines in a small village in the extreme north of South Vietnam. Those pages provided just enough information for me to file a Freedom of Information Act request for court-martial transcripts related to American crimes there. The military’s response to my request was an all too common one: the documents were inexplicably missing. But the government file was not entirely empty. Hundreds of pages of trial transcripts, sworn testimony, supporting documents, and the like had vanished into thin air, but the military could offer me something in consolation: a copy of the protective jacket that was once wrapped around the documents. I declined. Indeed, an astonishing number of marine court-martial records of the era have apparently been destroyed or gone missing. Most air force and navy criminal investigation files that may have existed seem to have met the same fate. Even before this, the formal investigation records were an incomplete sample at best; as one veteran of the secret Pentagon task force told me, knowledge of most cases never left the battlefield. Still, the War Crimes Working Group files alone demonstrated that atrocities were committed by members of every infantry, cavalry, and airborne division, and every separate brigade that deployed without the rest of its division—that is, every major army unit in Vietnam. The scattered, fragmentary nature of the case files makes them essentially useless for gauging the precise number of war crimes committed by U.S. personnel in Vietnam.46 But the hundreds of reports that I gathered and the hundreds of witnesses that I interviewed in the United States and Southeast Asia made it clear that killings of civilians—whether cold-blooded slaughter like the massacre at My Lai or the routinely indifferent, wanton bloodshed like the lime gatherers’ ambush in Binh Long—were widespread, routine, and directly attributable to U.S. command policies. And such massacres by soldiers and marines, my research showed, were themselves just a tiny part of the story. For every mass killing by ground troops that left piles of civilian corpses in a forest clearing or a drainage ditch, there were exponentially more victims killed by the everyday exercise of the American way of war from the air. Throughout South Vietnam, women and children were asphyxiated or crushed to death when their bunkers collapsed on them, burying them alive after direct hits from jets’ 500-pound bombs or 1,900-pound shells launched from offshore ships. Countless others, crazed with fear, bolted for safety when helicopters swooped toward their villages, only to have a door gunner cut them in half with bursts from an M-60 machine gun—and many others, who froze in place, suffered the same fate. There’s only so much killing a squad, a platoon, or a company can do. Face-to-face atrocities were responsible for just a fraction of the millions of civilian casualties in South Vietnam. Matter-of-fact mass killing that dwarfed the slaughter at My Lai normally involved heavier firepower and command policies that allowed it to be unleashed with impunity. This was the real war, the one that barely appears at all in the tens of thousands of volumes written about Vietnam. This was the war that Ron Ridenhour spoke about—the one in which My Lai was an operation, not an aberration. This was the war in which the American military and successive administrations in Washington produced not a few random massacres or even discrete strings of atrocities, but something on the order of thousands of days of relentless misery—a veritable system of suffering. That system, that machinery of suffering and what it meant for the Vietnamese people, is what this book is meant to explain. Copyright © 2013 by Nick Turse