Excerpt

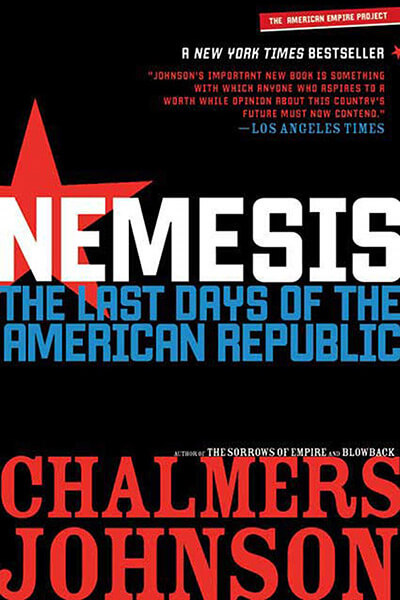

Nemesis

The Last Days of the American Republic

by Chalmers Johnson

Excerpt

Nemesis

The Last Days of the American Republic

by Chalmers Johnson

Prologue

The Blowback Trilogy

Who is Osama bin Laden really? Let me rephrase that. What is Osama bin Laden? He’s America’s family secret. He is the American president’s dark Doppelganger. The savage twin of all that purports to be beautiful and civilized. He has been sculpted from the spare rib of a world laid to waste by America’s foreign policy: its gunboat diplomacy, its nuclear arsenal, its vulgarly stated policy of “full-spectrum dominance,” its chilling disregard for non-American lives, its barbarous military interventions, its support for despotic and dictatorial regimes, its merciless economic agenda that has munched through the economies of poor countries like a cloud of locusts. . . . Now that the family secret has been spilled, the twins are blurring into one another and gradually becoming interchangeable.

Arundhati Roy,

The Guardian, September 27, 2001

Nemesis is the last volume of an inadvertent trilogy that deals with the way arrogant and misguided American policies have headed us for a series of catastrophes comparable to our disgrace and defeat in Vietnam or even to the sort of extinction that befell our former fellow “superpower,” the Soviet Union. Such a fate is probably by now unavoidable; it is certainly too late for mere scattered reforms of our government or bloated military to make much difference.

I never planned to write three books about the decline and fall of the American empire, but events intervened. In March 2000, well before 9/11, I published Blowback, based on my years of teaching and writing about East Asia. I had become convinced by then that some secret U.S. government operations and acts in distant lands would come back to haunt us. “Blowback” does not mean just revenge but rather retaliation for covert, illegal violence that our government has carried out abroad that it kept totally secret from the American public (even though such acts are seldom secret among the people on the receiving end). It was a term invented by the Central Intelligence Agency and first used in its “after-action report” about the 1953 overthrow of the elected government of Premier Mohammad Mossadeq in Iran. This coup brought to power the U.S.-supported Shah of Iran, who would in 1979 be overthrown by Iranian revolutionaries and Islamic fundamentalists. The Ayatollah Khomeini replaced the Shah and installed the predecessors of the current, anti-American government in Iran.1 This would be one kind of blowback from America’s first venture into illegal, clandestine “regime change”—but as the attacks of September 11, 2001, showed us all too graphically, hardly the only one.

My book Blowback was not much noticed in the United States until after 9/11, when my suggestion that our covert policies abroad might be coming back to haunt us gained new meaning. Many Americans began to ask—as President Bush did—“Why do they hate us?” The answer was not that some countries hate us because of our democracy, wealth, lifestyle, or values but because of things our government did to various peoples around the world. The counterblows directed against Americans seem, of course, as out of the blue as those airplanes on that September morning because most Americans have no framework that would link cause and effect. The terrorist attacks of September 11 are the clearest examples of blowback in modern international relations. In the initial book in this trilogy, I predicted the likely retaliation that was due against the United States, but I never foresaw the terrorist nature of the attacks, nor the incredibly inept reaction of our government.

On that fateful Tuesday morning in the early autumn of 2001, it soon became clear that the suicidal rammings of hijacked airliners into symbolically significant buildings were acts of what the Pentagon calls “asymmetric warfare” (a rare instance in which bureaucratic jargon proved more accurate than the term “terrorism” in common use). I talked with friends and colleagues around the nation about what group or groups might have carried out such attacks. The veterans of our largest clandestine war—when we recruited, armed, and sent into battle Islamic mujahideen (freedom fighters) in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union in the 1980s—did not immediately come to mind. Most of us thought of Chileans because of the date: September 11, 1973, was the day the CIA secretly helped General Augusto Pinochet overthrow Salvador Allende, the leftist elected president of Chile. Others thought of the victims of the Greek colonels we put in power in 1967, or Okinawans venting their rage over the sixty-year occupation of their island by our military. Guatemalans, Cubans, Congolese, Brazilians, Argentines, Indonesians, Palestinians, Panamanians, Vietnamese, Cambodians, Filipinos, South Koreans, Taiwanese, Nicaraguans, Salvadorans, and many others had good reason to attack us.

The Bush administration, however, did everything in its power to divert us from thinking that our own actions might have had something to do with such suicidal attacks on us. At a press conference on October 11, 2001, the president posed the question, “How do I respond when I see that in some Islamic countries there is vitriolic hatred for America?” He then answered himself, “I’ll tell you how I respond: I’m amazed that there’s such misunderstanding of what our country is about that people would hate us. I am—like most Americans, I just can’t believe it because I know how good we are.” Bush has, of course, never once allowed that the United States might bear some responsibility for what happened on 9/11. In a 2004 commencement address at the Air Force Academy, for instance, he asserted, “No act of America explains terrorist violence, and no concession of America could appease it. The terrorists who attacked our country on September 11, 2001, were not protesting our policies. They were protesting our existence.”2

But Osama bin Laden made clear why he attacked us. In a videotaped statement broadcast by Al Jazeera on October 7, 2001, a few weeks after the attacks, he gave three reasons for his enmity against the United States. The U.S.-imposed sanctions against Iraq from 1991 to 9/11: “One million Iraqi children have thus far died although they did not do anything wrong”; American policies toward Israel and the occupied territories: “I swear to God that America will not live in peace before peace reigns in Palestine . . .”; the stationing of U.S. troops and the building of military bases in Saudi Arabia: “and before all the army of infidels [American soldiers] depart the land of Muhammad [Saudi Arabia].”3 Not a word about Muslim rage against Western civilization; no sign that his followers were motivated by, as the president would put it, “hatred for the values cherished in the West [such] as freedom, tolerance, prosperity, religious pluralism, and universal suffrage”; no support for New York Times correspondent Thomas Friedman’s contention that the hijackers had left no list of demands because they had none, that “their act was their demand.”4

The attempt to disguise or avoid the policy-based reasons for 9/11 fed the rantings of Christian fundamentalists in the United States. Televangelist Pat Robertson, later joined by Jerry Falwell, declared that “liberal civil liberties groups, feminists, homosexuals, and abortion rights supporters bear some responsibility for [the] terrorist attacks because their actions have turned God’s anger against America,” and they launched a hate campaign against all Muslims. Jimmy Swaggart called Muhammad a “sex deviant” and a pervert and suggested that Muslim students in the United States be expelled.5 The Pentagon added its bit of insanity to this religious mix when army lieutenant general William G. “Jerry” Boykin, deputy undersecretary of defense for intelligence, argued in public in full uniform without subsequent official reprimand that “they” hate us “because we are a Christian nation,” that Bush was appointed by God, that the Special Forces are inspired by God, that our enemy is “a guy named Satan,” and that we defeat Islamic terrorists only “if we come at them in the name of Jesus.”6

Because Americans generally failed to consider seriously why we had been attacked on 9/11, the Bush administration was able to respond in a way that made the situation far worse. I believed at the time and feel no differently five years later that we should have treated the attacks as crimes against the innocent, not as acts of war. We should have proceeded against al-Qaeda the same way we might have against organized crime. It would have been wise to call what we were doing an “emergency,” as the British did in fighting the Malay guerrillas in the 1950s, not a “war.” The day after 9/11, Simon Jenkins, the former editor of the Times of London, insightfully wrote: “The message of yesterday’s incident is that, for all its horror, it does not and must not be allowed to matter. It is a human disaster, an outrage, an atrocity, an unleashing of the madness of which the world will never be rid. But it is not politically significant. It does not tilt the balance of world power one inch. It is not an act of war. America’s leadership of the West is not diminished by it. The cause of democracy is not damaged, unless we choose to let it be damaged.”7

Had we followed Jenkins’s advice we could have retained the cooperation and trust of our democratic allies, remained the aggrieved party of 9/11, built criminal cases that would have stood up in any court of law, and won the hearts and minds of populations al-Qaeda was trying to mobilize. We would have avoided entirely contravening the Geneva Conventions covering the treatment of prisoners of war and never have headed down the path of torturing people we picked up almost at random in Afghanistan and Iraq. The U.S. government would have had no need to lie to its own citizens and the rest of the world about the nonexistent nuclear threat posed by Iraq or carry out a phony preventive war against that country.

Instead, we undermined the NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) alliance and brought to power in Iraq allies of the Islamic fundamentalists in Iran.8 Contrary to what virtually every strategist recommended as an effective response to terrorism, we launched our high-tech military against some of the poorest, weakest people on Earth. In Afghanistan, our aerial bombardment “bounced the rubble” we had helped create there by funding, arming, and advising the anti-Soviet war of the 1980s and gave “warlordism, banditry, and opium production a new lease on life.”9 In Iraq our “shock and awe” assault invited comparison with the sacking of Baghdad in 1258 by the Mongols.10 In his address to Congress on September 20, 2001, President Bush declared that the coming battle was to be global, Manichean, and simple. You are, he said, either “with us or against us” (failing to acknowledge that both Jesus and Lenin used the phrase first). His actions would ensure that, in the years to come, there would be ever more people around the world “against us.”11

As I watched these post-9/11 developments, it became apparent to me that, even more than in most past empires, a well-entrenched militarism lay at the heart of our imperial adventures. It is a sad fact that the United States no longer manufactures much—with the exception of weaponry. We are without question the world’s greatest producer and exporter of arms and munitions on the planet. Although we are going deeply into debt doing so, each year we spend more on our armed forces than all other nations on Earth combined. In The Sorrows of Empire, I tried to analyze the nature of this militarism and to expose the harm it was doing, not only to others but to our own society and governmental system.

After all, we now station over half a million U.S. troops, spies, contractors, dependents, and others on more than 737 military bases spread around the world. These bases are located in more than 130 countries, many of them presided over by dictatorial regimes that have given their citizens no say in the decision to let us in. The Pentagon publishes an inventory of the real estate it owns in its annual Base Structure Report, but its official count of between 737 and 860 overseas installations is incomplete, omitting all our espionage bases and a number of others that are secret or could be embarrassing to the United States. For example, it leaves out the air force base at Manas in Kyrgyzstan, formerly part of the Soviet Union and today part of our attempt to roll back the influence of the Soviet Union’s successor state, Russia, and to control crucial Caspian Sea oil. It even neglects to mention the three bases built in tiny Qatar over the past few years, the headquarters for our high command during the invasion of Iraq in 2003, so as not to embarrass the emir of that country, who invited in our “infidel” soldiers. This same kind of embarrassment to the government of Saudi Arabia, not to mention the public displeasure of the Saudi national Osama bin Laden, forced us to move our forces out of that country and to Qatar in the years immediately preceding the assault on Iraq.

The purpose of all these bases is “force projection,” or the maintenance of American military hegemony over the rest of the world. They facilitate our “policing” of the globe and are meant to ensure that no other nation, friendly or hostile, can ever challenge us militarily. In The Sorrows of Empire I described this planet-spanning baseworld, including the history and development of various installations, the creation of an airline—the Air Mobility Command—to connect them to one another and to Washington, and the comforts available to our personnel through the military’s various “Morale, Welfare, and Recreation” (MWR) commands. Some of the “rest-and-recreation” facilities include the armed forces ski center at Garmisch in the Bavarian Alps, over two hundred military golf courses around the world, some seventy-one Learjets and other luxury aircraft to fly admirals and generals to such watering holes, and luxury hotels for our troops and their families in Tokyo, Seoul, on the Italian Riviera, at Florida’s Disney World, and many other places.

Americans cannot truly appreciate the impact of our bases elsewhere because there are no foreign military bases within the United States. We have no direct experience of such unwelcome features of our military encampments abroad as the networks of brothels around their main gates, the nightly bar brawls, the sexually violent crimes against civilians, and the regular hit-and-run accidents. These, together with noise and environmental pollution, are constant blights we inflict on local populations to maintain our lifestyle. People who live near our bases must also put up with the racial and religious insults that our culturally ignorant, high-handed troops often think is their right to dish out. Imperialism means one nation imposing its will on others through the threat or actual use of force. Imperialism is a root cause of blowback. Our global garrisons provide that threat and are a cause of blowback.

It takes a lot of people to garrison the globe. Service in our armed forces is no longer a short-term obligation of citizenship, as it was back in 1953 when I served in the navy. Since 1973, it has been a career choice, one often made by citizens trying to escape from the poverty and racism that afflict our society. That is why African-Americans are twice as well represented in the army as they are in our population, even though the numbers have been falling as the war in Iraq worsens, and why 50 percent of the women in the armed forces are minorities. That is why the young people in our colleges and universities today remain, by and large, indifferent to America’s wars and covert operations: without the draft, such events do not affect them personally and therefore need not distract them from their studies and civilian pursuits.

American veterans of World War II, Korea, or Vietnam simply would not recognize life in the modern armed services. As the troops no longer do KP (“kitchen police”), the old World War II movie gags about GIs endlessly peeling mountains of potatoes would be meaningless today. We farm out such work to private military companies like KBR (formerly Kellogg Brown & Root), a subdivision of the Halliburton Corporation, of which Dick Cheney was CEO before he became vice president. It is an extremely lucrative business for them. Of the $57 billion that was appropriated for Iraq operations at the outset of the invasion, a good third of it went to civilian contractors to supply meals, drive trucks and buses, provide security guards, and do all other housekeeping work to maintain our various bases.

When you include its array of privately outsourced services, our professional, permanent military currently costs around three-quarters of a trillion dollars a year. This amount includes the annual Defense Department appropriation for weapons and salaries of more than $425 billion (the president’s request for fiscal year 2007 was $439.3 billion), plus another $120 billion for military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, $16.4 billion for nuclear weapons and the Department of Energy’s weapons laboratories, $12.2 billion in the Military Construction Appropriations Bill, and well over $100 billion in pensions, hospital costs, and disability payments for our veterans, many of whom have been severely wounded.12 But we are not actually paying for these expenses. Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian investors are. We are putting them on the tab and so running the largest governmental as well as trade deficits in modern economic history. Sooner or later, our militarism will threaten the nation with bankruptcy.

Until the 2004 presidential election, ordinary citizens of the United States could at least claim that our foreign policy, including our illegal invasion of Iraq, was the work of George Bush’s administration and that we had not put him in office. In 2000, Bush lost the popular vote and was appointed president thanks to the intervention of the Supreme Court in a 5–4 decision. In November 2004, regardless of claims about voter fraud, Bush won the popular vote by over 3.5 million ballots, making his wars ours. The political system failed not because we elected one candidate rather than another as president, since neither offered a responsible alternative to aggressive war and militarism, but because the election essentially endorsed and ratified the policies we had pursued since 9/11.

Whether Americans intended it or not, we are now seen around the world as having approved the torture of captives at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, at Bagram Air Base in Kabul, at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, and at secret prisons around the world, as well as having seconded Bush’s claim that, as a commander in chief in “wartime,” he is beyond all constraints of the Constitution or international law. We are now saddled with a rigged economy based on record-setting deficits, the most secretive and intrusive American government in memory, the pursuit of “preventive” war as a basis for foreign policy, and a potential epidemic of nuclear proliferation as other nations attempt to adjust to and defend themselves from our behavior, while our own, already staggering nuclear arsenal expands toward first-strike primacy.

The crisis the United States faces today is not just the military failure of Bush’s policies in Iraq and Afghanistan, the discrediting of America’s intelligence agencies, or our government’s not-so-secret resort to torture and illegal imprisonment. It is above all a growing international distrust and disgust in the face of our contempt for the rule of law. Article 6 of the U.S. Constitution says, in part, “all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land.” The Geneva Conventions of 1949, covering the treatment of prisoners of war and civilians in wartime, are treaties the U.S. government promoted, signed, and ratified. They are therefore the supreme law of the land. Neither the president, nor the secretary of defense, nor the attorney general has the authority to alter them or to choose whether or not to abide by them so long as the Constitution has any meaning.

Despite the administration’s endless propaganda about bringing freedom and democracy to the people of Afghanistan and Iraq, most citizens of those countries who have come into contact with our armed forces (and survived) have had their lives ruined. The courageous, anonymous young Iraqi woman who runs the Internet Web site Baghdad Burning wrote on May 7, 2004: “I don’t understand the ‘shock’ Americans claim to feel at the lurid pictures [from Abu Ghraib prison]. You’ve seen the troops break down doors and terrify women and children . . . curse, scream, push, pull, and throw people to the ground with a boot over their head. You’ve seen troops shoot civilians in cold blood. You’ve seen them bomb cities and towns. You’ve seen them burn cars and humans using tanks and helicopters. . . . I sometimes get e-mails asking me to propose solutions or make suggestions. Fine. Today’s lesson: don’t rape, don’t torture, don’t kill, and get out while you can—while it still looks like you have a choice. . . . Chaos? Civil war? We’ll take our chances—just take your puppets, your tanks, your smart weapons, your dumb politicians, your lies, your empty promises, your rapists, your sadistic torturers and go.”13

In July 2004, Zogby International Surveys polled 3,300 Arabs in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. When asked to identify “the best thing that comes to mind about America,” virtually all respondents answered “nothing at all.” There are today approximately 1.3 billion Muslims worldwide, some 22 percent of the global population. Through our policies, we have turned virtually all of them against the United States.14

Unfortunately, our political system may no longer be capable of saving the United States as we know it, since it is hard to imagine any president or Congress standing up to the powerful vested interests of the Pentagon, the secret intelligence agencies, and the military-industrial complex. Given that 40 percent of the defense budget is now secret as is every intelligence agency budget, it is impossible for Congress to provide effective oversight even if its members wanted to. Although this process of enveloping such spending in darkness and lack of accountability has reached its apogee with the Bush administration, the Defense Department’s “black budgets” go back to the atomic-bomb-building Manhattan Project of World War II. The amounts spent on the intelligence agencies have been secret ever since the CIA was created in 1947.

If our republican form of government is to be saved, only an upsurge of direct democracy might be capable of doing so. In the spring of 2003, before our troops could be launched into Iraq, some 10 million people in all the genuine democracies on Earth demonstrated fervently against the onrushing war, against George Bush, and for democracy, including an estimated 1,750,000 people in London, 750,000 in New York, 2,500,000 in Rome, 1,500,000 each in Madrid and Barcelona, 800,000 in Paris, and 500,000 in Berlin.15 However, the sole victory of this movement came on March 14, 2004, with the election of Spanish prime minister José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. If democracy means anything at all, it means that public opinion matters. Zapatero understood that over 80 percent of Spaniards opposed Bush’s war against Iraq, and he immediately withdrew all Spanish forces. The task of democrats worldwide is to replicate the Spanish achievement in their own societies.

In early 2003, on the eve of the invasion of Iraq, I was putting the finishing touches on my portrait of the global reach of American military bases. In it, I suggested the sorrows already invading our lives, which were likely to be our fate for years to come: perpetual war, a collapse of constitutional government, endemic official lying and disinformation, and finally bankruptcy. At book’s end, I advocated reforms intended to head off these outcomes but warned that “[f]ailing such a reform, Nemesis, the goddess of retribution and vengeance, the punisher of pride and hubris, waits impatiently for her meeting with us.”

This line inspired poet John Shreffler to pen his conception of such a goddess, American style. In the poem “Neighborhood Girl,” he imagines her as an adolescent tomboy from elsewhere, no doubt cruel and merciless when playing the divine role assigned to her but also the niece of Erato, the muse of love poetry. He wrote in part:

She’s new to the neighborhood, her family just moved in

From Greece or somewhere, she’s a great, tall, gawky girl

With braces and earrings and uneven skin:

Hormones and acne, her change is coming in, . . .

Her name is Nemesis and she’s just moved in,

She’s new to the neighborhood, she’s checking it out.16

As the Dutch folklorist Micha F. Lindemans reminds us, “Nemesis is the goddess of divine justice and vengeance. . . . [She] pursues the insolent and the wicked with inflexible vengeance. . . . She is portrayed as a serious-looking woman with in her left hand a whip, a rein, a sword, or a pair of scales.”17 Nemesis is a bit like Richard Wagner’s Valkyrie Brünnhilde, except that Brünnhilde collects heroes, not fools and hypocrites. Nonetheless, Brünnhilde’s way of announcing herself applies also to Nemesis: “Nur Todgeweihten taugt mein Anblick” (Only the doomed see me).18

I remain hopeful that Americans can still rouse themselves to save our democracy. But the time in which to head off financial and moral bankruptcy is growing short. The present book is my attempt to explain how we got where we are, the manifold distortions we have imposed on the system we inherited from the Founding Fathers, and what we would have to do to avoid our appointment with Nemesis, now that she’s in the neighborhood.

Copyright © 2006 by Chalmers Johnson