Excerpt

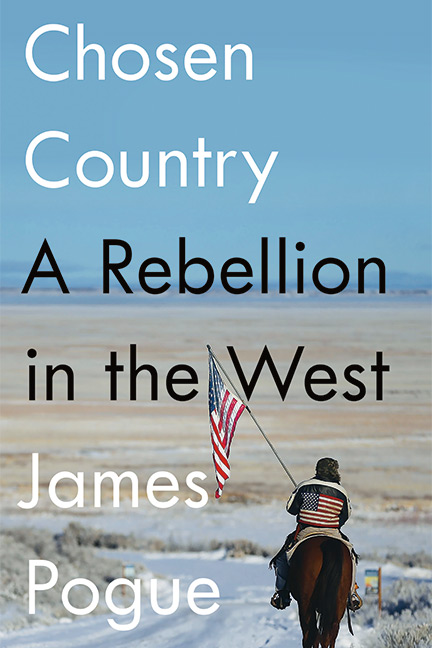

Chosen Country

A Rebellion in the West

by James Pogue

Excerpt

Chosen Country

A Rebellion in the West

by James Pogue

CHAPTER 1

The Best People You Could Possibly Imagine

It was snowing the night I got to the refuge. It had snowed for almost the entire drive from Portland, and it was only with some difficulty and by the use of tire chains that I’d made it over Mount Hood and through the desert. The drive to Burns, where I checked into what the clerk told me was the last room at the local Days Inn, had taken eight hours, which is not so much longer than it takes to drive in any direction from the town to a city of any size—by measure of distance from an interstate it is the remotest corner of the lower forty-eight. The snow was six inches deep on the streets and falling fast, and there were hardly any cars on the road aside from deputies’ cruisers, bearing the markings of counties from all across Oregon. These reinforcements and the riot of rented SUVs in the parking lot at the Days Inn were the only indication that the little town had become the host of an insurrection, suddenly one of the biggest news stories in the world. The dingy Thai restaurant on the silent main drag was closed, with a sign in the window like something out of a western, reading “Sorry Gone to Bend for Supplies.”

I was in bad need of a hamburger, a few beers, and bed before midnight—but before I’d managed to eat or even set foot in my motel room I’d gotten a text from my mom, who was watching CNN. “James,” she said, “they’re moving all kinds of bulldozers and things out there and it sounds crazy.” She asked me to stay in for the night. I hadn’t had any service since I hit the mountains and had no idea what was happening, but on the strength of her worry I immediately pulled out my atlas of Oregon and set off on the thirty-mile drive down State Route 205. In the snowstorm and the dark the road was almost indistinguishable from the flat sage rangeland, which in turn was entirely indistinguishable from the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge itself, which I would have never been able to find if it weren’t for the dozens of news trucks idling on a little rise at the entrance to the refuge headquarters. I parked, shook out a cigarette, and wandered into the halogen-lit portion of the snowstorm. LaVoy Finicum, who had fashioned himself a spokesman for what was going on, was sitting on a camp chair under a tarp with a cowboy hat on his head and a rifle across his knees, having just finished giving the live interview that would make him famous. “They’re not going to just come up to a guy holding a rifle and put cuffs on him,” he had said, and when asked what exactly he meant by that he went on. “I have been raised in the country all my life. I love dearly to feel the wind on my face, to see the sunrise, to see the moon in the night. I have no intention of spending any of my days in a concrete box.” The message that the occupiers were ready to die before being arrested was reported in papers all over the world.

We greeted each other with a nod. Past him was Jason Patrick, who was on the phone and smoking a cigarette. I waved to him, and he recognized me and waved back, indicating by sign language that he’d catch up with me when his call was done. He was wearing, as he always did, apparently even in the cold of a desert snowstorm, a cheap and oversize suit jacket, with a baggy, blue button-front shirt and khakis. He had salt-and-pepper hair to match a salt-and-pepper beard and bore a plausible-enough resemblance to a much thicker George Clooney that during the standoff “Clooney” became his radio call sign. Eventually it just became his name. He smoked constantly. A friend of mine who knows him once described him as “the smokingest dude on the whole planet.” It’s hard to imagine what he must have done during his various stints in jail.

“Hey, man,” he said and lit another cigarette. We caught up for a few seconds before my phone rang. It was a friend of his and a friendly acquaintance of mine named Brandon Rapolla, a giant, Guamanian marine whom I had met the same day I met Jason, at a different standoff the previous April. I mentioned to Jason who it was and he asked for my phone. I shrugged and gave it to him. “Sup, bro,” he said, and there was a brief exchange while Brandon realized who was talking. “Yeah,” Jason said, “I’m just up here watching LaVoy’s back now.”

A man in fatigues approached and pulled me aside. “You know how dangerous it is here tonight?” he asked. I said I didn’t. “They’re talking about coming in,” he said, giving me to understand that by “they” he meant the FBI. I said I hadn’t known that, and he indicated with his head to the north end of the rise where an earth mover was being positioned by some enthusiastic occupiers to block a possible assault party from coming down the icy access road to the refuge headquarters. Beside the access road someone had dropped off about half a cord of dried hardwood, and three or four men holding rifles and wearing camo and balaclavas were standing around in the snow, slowly feeding a fire and watching the gravel lot, where we were standing and where LaVoy was out under his tarp. High above us, in a creaking, steel fire tower, ninety feet high, the shadow of a sniper could be seen pacing. The sat trucks and rented Ford Explorers used by the reporters began pulling out of the front lot, and the feel of the place was intensely dark and paranoid. “There’s a drone flying around—watch out for that,” the man said. All the people who said they saw it described it as a black object with about a six-foot wingspan. I never saw the drone.

I turned back to Jason, who was now in a biting argument with Brandon on my phone. “You know they’re not going to do anything, right?” he said, meaning law enforcement. “They’re going to wait and wait and wait and wait.”

He went quiet for a moment and there began a long and bitter exchange about how Brandon’s militia hadn’t shown up yet.

“I would say right back that I’m not happy about the beginning,” he said into the phone. There were more words. “You know I don’t want to hash that out because I’m not going to lose sleep over it. You have to understand I’m just here.”

There was a pause while Brandon talked. “Well, listen,” Jason said. “Think of the last sentence of the Declaration of Independence: a strong reliance on divine providence.” He paused. “It happened how it happened. There’s a bunch of ranchers on board, so get in here.”

Brandon spoke for a while, presumably saying something about how poorly equipped the occupiers were to conduct an armed rebellion, because Jason suddenly got angry.

“I’m going to come and motherfuck all you military types,” he said. “Because your security ops stuff? In America? It’s a bunch of bullshit. All you can do here is stand up with pitchforks and torches and you say fuck no. So just put that fucking shit down, stop playing at GI Joe, and listen to the civilian who knows. We can win, but you guys have to stop buttfucking each other and we’ll fix it.”

He turned to me and winked. “Especially with those purple panties you wear,” he said into the phone. He turned back to me. “See? We’re in deep now.”

Brandon said something and Jason laughed. “Yeah, well, fucking get here and we’ll get real deep,” he said. “Okay. I’m going to give you back and go see how LaVoy’s doing.”

I got back on the phone with Brandon, who said he had to work but was planning on coming down in a couple of days. He was obviously conflicted about what was happening, which seemed out of character. He had been at the standoff at the Bundys’ family ranch, in 2014, and he had been the “head of security” at the militia standoff where I’d met him, the year before at a gold mine in southern Oregon. That one, despite being no smaller and no less crazy to witness, had barely made the national papers—which was partly a product of the fact that it didn’t have any wild-eyed charmers like LaVoy doing interviews at the front lines and partly, at least so far as I could figure it, because until the ferment of 2016 a wild standoff in the middle of nowhere had seemed too strange and random to mean much in a national sense. Now, just a few months later and a few counties over, the Malheur refuge looked like an expression of exactly where the country was headed.

But both of the earlier events, from Brandon’s perspective, had gone well, and from a tactical standpoint there wasn’t anything all that different about this one—except for a feeling of heaviness and foreboding that even Jason, who had been in on the plan since the beginning, seemed to share.

Brandon asked if he could call me back. The last time I’d seen him, six months earlier, I had encountered him by chance in his blue Dodge pickup on I-5 south of Eugene. We had convoyed through a rainstorm for an hour or so and then given each other a wave when we parted, the entire thing passing at seventy-five miles an hour without us exchanging a word, and we had a general sense that we could each trust the other. A few minutes later he called. “Listen, man,” he said. “I’ve just been calling around. We have really good intel that the FBI is going to move in there tonight. And I’m wondering if you want to stay overnight with Jason, to be a sort of witness if some bad shit goes down.”

This was only the first of many times over the next weeks and months that I’d be asked to put myself in a compromising position, and I realized only later how irretrievably compromised a position it was. In any case, I said yes, knowing that he was asking me to be, essentially, a human shield. I wandered over to the fire, where a few people were still getting the dozers in place to block the road. I asked if they really thought there’d be a raid. “That’s the intel we got,” one of them, a Mormon extremist and HVAC contractor from Las Vegas named Brand Thornton, told me. “Our leaders briefed me on it. And the way I think it happens is we move this stuff up here”—he pointed to the dozers—“make a show of force, and I think they say to the superior officers, you know … I’m not sure this is such a good idea.… We have a lot more people here than you see.”

We spoke for a minute about how many people were at the site, how little sleep they were getting, how everyone looked out for one another and loved one another. A thin young man in fatigues and a balaclava interjected, speaking so slowly that at first I thought he was stoned. “And we’re good people,” he said, nakedly baffled that the FBI had not chosen to see it this way. There was a long pause. “We’re, like, the best people that you could possibly imagine.”

Copyright © 2018 by James Pogue

=