Excerpt

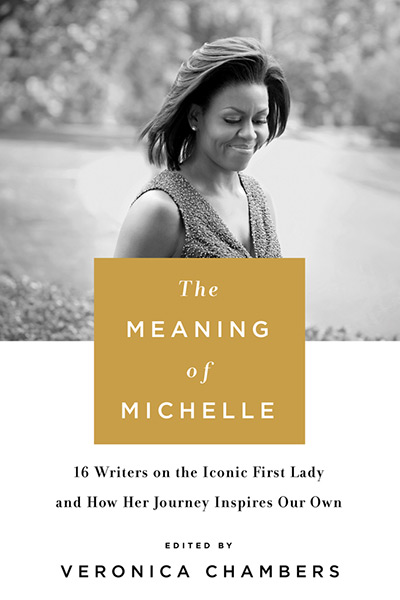

The Meaning of Michelle

16 Writers on the Iconic First Lady and How Her Journey Inspires Our Own

by Veronica Chambers

Excerpt

The Meaning of Michelle

16 Writers on the Iconic First Lady and How Her Journey Inspires Our Own

by Veronica Chambers

Introduction: Homegirls

VERONICA CHAMBERS

Barack Obama’s historic run for presidency coincided directly with me becoming a mother. I came back to the United States after a year in France with my husband and two things happened: I had a baby and Obama cinched the nomination. My earliest recollections of motherhood seem to have as a constant backdrop the Obamas on TV, on NPR, in the newspapers and magazines I read. Their name quickly became a sort of lullaby that we used to put the baby to sleep: Oh, Oh, Obama. Oh, Oh, Obama. When I voted for him that November, my daughter was in a sling across my chest. I remember stepping into the voting booth with her and just taking a moment of feeling her breathe against me and thinking of Obama’s iconic line, while we breathe we hope, as I pulled the lever and cast my vote.

By the inauguration, I was in full pash mode with Michelle Obama; so much so that I covered my office wall with designer sketches of her inauguration dress. I began my day with New York magazine’s “The Michelle Obama Look Book.” I have loved clothes my whole life, but Michelle Obama took my style obsession to a new level. Black women have shaped and supported the American fashion industry from the earliest days. In 1860, Elizabeth Keckley, a former slave, moved to Washington and set up business as a seamstress. Among her many esteemed clients were Mary Todd Lincoln. From the Harlem Renaissance to the 1960s, 1970s and beyond, black women were both muses and creators of fashion. I was like so many Black women who had grown up loving style icons from Dorothy Dandridge to Diana Ross, to the one-name icons that ranged from Iman to Solange. But we’d never had anyone like Michelle before. She wasn’t a model, an actress or a musician. She was, quite simply, the star of her own life—and that was a game changer for Black women, and it turned out all women, in the early twenty-first century.

I was as obsessed as everyone else with her arms. When I began to get up before 5 a.m. to work out with a trainer two days a week before getting to work, I thought of Michelle Obama in Chicago. At the time, we lived in a suburb of New York and getting to the trainer involved leaving my home at 5 a.m. to take two trains into the city. But I was inspired by what Cornell McClellan, her Chicago trainer, told Women’s Health magazine: “She’s truly committed herself to the importance of health and fitness. I believe the purpose of training is to tighten up the slack, toughen the body, and polish the spirit. To do that, we take a holistic approach that includes strength, cardiovascular, and flexibility training.” At the end of the day, I think that’s what was behind all the shine that her biceps received in the media, both in the United States and all around the world: here was a busy woman who had found the time to take care of herself. She was not last on her to-do list, after her amazing kids and her extraordinary husband. She put herself first—and had done so for a long time.

Around the same time, my daughter, then a toddler, had transformed her nursery lullaby of “Oh, Oh, Obama” into a full-scale Elektra crush on the President of the United States. “Me no like ’Chelle,” she would say, glowering at the TV. I was horrified. I wasn’t really worried that I was raising a future home wrecker (though the thought did cross my mind). But more, I felt like somehow I’d failed to convey to my daughter that she and her cohort had been lucky enough to be born with the most amazing role model in the White House, the kind of role model that was unlike any enjoyed by previous generations of brown-skinned girls. “We love ’Chelle,” I quickly course-corrected as I brought home every one of the commemorative photo books that were published in those early years of the administration. “’Chelle is awesome. ’Chelle is the best.” Eventually, my daughter got the memo and “Me no like ’Chelle” turned into “I want a play date with ’Chelle and her daughters.” To which I replied, “We all do, honey. We all do.”

More than one essayist in this anthology refers to the First Lady as ’Chelle. There’s an intimacy we felt with her from the beginning. The mainstream media seemed flummoxed by her lack of political posturing: Is she on board with this whole political spouse thing? Do the Obamas want it (meaning the presidency) badly enough? But it was that very same lack of fake warmth and glossed-over royal waves that let us, in the Black community, know that she was real, and this is what won our affection. She wasn’t going to bare her soul because, as we used to say on the block, “I don’t know you like that.” She wasn’t going to figure out how and to what extent she’d let us in until the deal was done and we agreed, through the formal process of voting, that they would be our First Family.

Michelle Obama quickly set about making the White House America’s home, and it was, of course, during the First Lady’s history-setting poetry jam that Lin-Manuel Miranda first debuted what would become the iconic musical Hamilton. One of the songs from that musical describes how after the revolution, “the world turned upside down.” The election of Barack Obama as the forty-fourth president was not as tumultuous as the American Revolution, but it did coincide with the world turning upside down—in ways both great and horrible—for Black Americans. So we can’t look at Michelle Obama and all she has come to represent without considering the corresponding rise of Black women in other fields. The Obamas did not come into office under the auspices of an imagined blue-screen Camelot. Rather, while they moved into the White House, America basked in the genius of Shondaland, the world according to Shonda Rhimes, where we learned the importance of finding your person and getting good with the dark and twisty parts of ourselves. Then Kerry Washington joined the Shonda party and we all got Poped, basking in the power of an onscreen fixer, based on Judy Smith, a real-life Washington, D.C., fixer, a woman who confidently and stylishly stepped into her power. I believe that someday, the GIF of Olivia Pope intoning, “It’s handled,” will be installed in the National Women’s History Museum in Washington, D.C. Once that museum is built, that is.

And yet, for all that Black women have achieved over the last eight years, there have been devastating, unspeakable and senseless acts of violence against members of our community—the kind of killings that brought to mind the 1930s and the days of unchecked lynching. As the singer and fashion muse Solange wrote after the Charleston Church shooting, “Was already weary. Was already heavy hearted. Was already tired. Where can we be safe? Where can we be free? Where can we be black?”

The Black Lives Matter movement, started by three young women, is as powerful a testimony to the advancements of Black women as any move to the corner office or Capitol Hill. Michelle Obama did not flinch from the more socially heartbreaking moments of the Obamas’ eight years in the White House. Witness her defiant call to “Bring Back Our Girls” after 276 Nigerian schoolgirls were kidnapped by a terrorist regime. At the same time, she seems determined to remind us that—despite the challenges within and outside of our community—Blackness is not burdensome, and we, like all other human beings, have joy as a birthright, one we must work, sometimes daily, to claim. When she made us laugh—from her mom-dancing with Jimmy Fallon to her Lil Jon parody, “Turnip for What,” to the College Rap with Saturday Night Live star Jay Pharoah—she reminded us how good it feels when you can be at home in your own skin and therefore at home in your world.

I have, over the years, been gifted with an incredible posse of homegirls. They are Black, white, Latina and Asian (and sometimes, a blend of these census-like categories). These women have my back. They were there when I jumped the broom and married my husband. They have seen me do my ugly cry and danced with me, on those sweet occasions, when we partied until night turned to day.

But the very first homegirl I ever had was named Renee Neufville. It was the early 80s and we lived in Brooklyn, then a land of Kangol caps and Adidas sneakers, name belts, gold chains and fronts, and door knocker earrings. We were in elementary school and I knew that Renee was my homegirl because everyone said so. “What’s up with your homegirl?” they’d ask. Or if I was out jumping double Dutch without Renee, they would ask, “Where your homegirl at?”

My parents were immigrants, so “homegirl” wasn’t a word we used at home. It didn’t just roll off of my tongue, back then. My mother and her friends, all Latinegras or Black Latinas, called each other, ’manita or comadre. So that term, “homegirl,” took some getting used to.

At the end of the day when our mothers leaned out of windows and yelled for us to come home, dinner was on the table, I would walk Renee to her house, which was around the corner and about a block away. Then she would turn around and walk me home. It seemed like there was no shortage of things for us to talk about: it was like we were, in dialogue, reading a book that had no chapters and no end. There seemed to be no place to break. We walked each other back and forth until our mothers threatened to take a switch to our behinds. In this very literal way, I came to think of a homegirl as someone with whom the soul conversation is so deep and so stirring that you keep walking each other home.

As our editor, Elisabeth Dyssegaard, and I put together this collection, I marveled at the way this anthology is less an intellectual analysis of Michelle Obama as First Lady and more a series of musings, reminiscences and pash notes to Michelle Obama as homegirl, the woman who (alongside Mindy Kaling) we all want to be friends with. Dr. Sarah Lewis connects the dots between Frederick Douglass’s passion for imagery that represented African Americans with dignity and grace and the iconic portraits of Michelle O by photographers like Annie Leibovitz. Dr. Brittney Cooper ponders the mutual admiration society of our First Lady and Beyoncé. Damon Young talks about how Michelle’s beauty and boldness first swayed his vote. Anyone who has ever read his Very Smart Brothas knows that his blog name is not mere hyperbole. His essay will make you think—and laugh out loud. Alicia Hall Moran and Jason Moran describe their up-close glimpses of the Obamas and how they navigate the paths of marriage, partnership, power and creativity.

Novelist Benilde Little, whose books often limn the world of the Black elite with Edith Wharton–like knowingness, talks about Michelle Obama and authenticity. And Phillipa Soo, fresh off her Tony-nominated run as Eliza Hamilton in Hamilton, talks about why Michelle O is the best of wives and the best of women.

Chirlane McCray gives us her unique perspective on FLOTUS from her role as First Lady of New York City. Cathi Hanauer talks about getting married the same year as Michelle Obama—1992—and how she and her husband, like the President and First Lady, balanced marriage, parenthood and careers. Tiffany Dufu, author of Drop the Ball: Achieving More by Doing Less, muses on how Michelle Obama is perfect precisely because she’s not trying to be. And Ylonda Gault Caviness shares how close so many of us feel to the First Lady in her essay, “We Go Way Back.”

Rebecca Carroll weaves a powerful connection between Michelle O and Zora Neale Hurston in her essay, “She Loves Herself When She Is Laughing: Michelle Obama, Taking Down a Stereotype and Co-Creating a Presidency.”

In “She Slays,” Tanisha Ford talks about Michelle Obama’s style and the importance of fashion in the cultural history. As Ford writes, “Style has always mattered to Black Americans. We have been enslaved, have been denied equal rights, and have been, and continue to be, the targets of state-sanctioned and vigilante violence. Clothing is a way we reclaim our humanity, express our creativity, celebrate our roots, and forge political solidarities. We style out as a mode of survival.”

Marcus Samuelsson takes us behind the scenes in his role as chef of the Obamas’ first White House state dinner, but also—as an Ethiopian-born, Swedish-raised, Harlemite—talks about the importance of Michelle Obama as a role model to girls and women on a global scale. Karen Hill Anton writes to us from the countryside of Japan where she has made her home for forty years. In her essay, “The Freedom to Be Yourself,” she talks about how Michelle Obama has inspired her and how her life in Japan has allowed her to live as an American first. Rebecca Carroll takes a deep look at Michelle O’s sense of humor and the confidence and grace that is at its base. In her essay “Making Space,” Roxane Gay explains how Michelle Obama’s arc of authenticity inspires us all: “Whenever I think about Michelle Obama, I think, ‘When I grow up, I want to be just like her.’ I want to be that intelligent, confident, and comfortable in my own skin.”

The Obamas are now preparing to leave the White House and step, for the first time in a decade, into semi-private life. For those of us who think of Michelle as more than our First Lady, it is clear that we will struggle with our goodbyes in much the same way that me and my friend Renee could not stop our dreaming and scheming for the impertinent interruptions of homework, dinner and sleep.

The goodbyes will be tough but I’m hopeful that the gratitude will be mighty and ongoing. There’s a through line of thankfulness that runs through this anthology, so let me be the first to start the praise song: Thank you for inspiring us, thank you for letting us in and lifting us up. Thank you for showing us how to infuse old roles with new imagination and grace.

The writer Brené Brown writes of how essential it is to own our belonging that there should be “no more hustling for worthiness.” But when race remains such a powder keg issue, this can be a hard thing even for the most affluent and educated among us to do. And yet, this reach toward confidence in our belonging is perhaps one of the most important struggles of our time. James Baldwin knew this, and it is why he once wrote that he hoped future generations of Black Americans would remember that “your crown has been bought and paid for. All you have to do is wear it.” Thank you, Michelle Obama, for showing us how to wear it.

Copyright © 2017 by Veronica Chambers