Excerpt

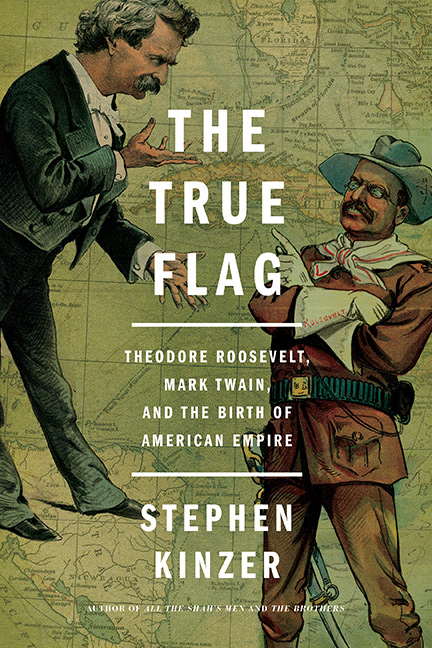

The True Flag

Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire

by Stephen Kinzer

Excerpt

The True Flag

Theodore Roosevelt, Mark Twain, and the Birth of American Empire

by Stephen Kinzer

Introduction

How should the United States act in the world? Americans cannot decide. For more than a century we have debated with ourselves. We can’t even agree on the question.

Put one way: Should we defend our freedom, or turn inward and ignore growing threats?

Put differently: Should we charge violently into faraway lands, or allow others to work out their own destinies?

Our enthusiasm for foreign intervention seems to ebb and flow like the tides, or swing back and forth like a pendulum. At some moments we are aflame with righteous anger. Confident in our power, we launch wars and depose governments. Then, chastened, we retreat—until the cycle begins again.

America’s interventionist urge, however, is not truly cyclical. When we love the idea of intervening abroad and then hate it, we are not changing our minds. Both instincts coexist within us. Americans are imperialists and also isolationists. We want to guide the world, but we also believe every nation should guide itself. At different times, according to circumstances, these contrary impulses emerge in different proportions. Our inability to choose between them shapes our conflicted approach to the world.

Eminent figures have led the United States into conflicts from Indochina to Central America to the Middle East. Others rose to challenge them. They were debating the central question of our foreign policy: Should the United States intervene to shape the fate of other nations? Much of what they said was profound. None of it was original.

For generations, every debate over foreign intervention has been repetition. All are pale shadows of the first one.

Even before that debate broke out, the power of the United States was felt beyond North America. In 1805 a fleet dispatched by President Thomas Jefferson defeated a Barbary Coast pasha who was extorting money from American vessels entering the Mediterranean. Half a century later, President Millard Fillmore sent a fleet of “black ships” to force Japan to open its ports to American traders. Those were isolated episodes, though, and not part of a larger plan to spread American power. After both of them, troops returned home. Civil war enveloped the United States from 1861 to 1865. Over the decades that followed, Americans concentrated on binding their national wounds and settling the West. Only after the frontier was officially declared closed in 1890 did some begin to think of the advantages that might lie in lands beyond their own continent. That brought the United States to the edge of the world stage. In 1898, Americans plunged into the farthest-reaching debate in our history. It was arguably even more momentous than the debate over slavery, because its outcome affected many countries, not just one. Never has the question of intervention—how the United States should face the world—been so trenchantly argued. In the history of American foreign policy, this is the mother of all debates. As the twentieth century dawned, the United States faced a fateful choice. It had to decide whether to join the race for colonies, territories, and dependencies that gripped European powers. Americans understood what was at stake. The United States had been a colony. It was founded on the principle that every nation must be ruled by “the consent of the governed.” Yet suddenly it found itself with the chance to rule faraway lands. This prospect thrilled some Americans. It horrified others. Their debate gripped the United States. The country’s best-known political and intellectual leaders took sides. Only once before—in the period when the United States was founded—have so many brilliant Americans so eloquently debated a question so fraught with meaning for all humanity. The two sides in this debate represent matched halves of the divided American soul. Should the United States project power into faraway lands? Yes, to guarantee our prosperity, save innocent lives, liberate the oppressed, and confront danger before it reaches our shores! No, intervention brings suffering and creates enemies! Americans still cannot decide what the Puritan leader John Winthrop meant when he told his followers in 1630, “We shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.” He wanted us to build a virtuous society that would be a model for others! Wrong, he wanted us to set out into a sinful world and redeem it! Forced to choose between these two irreconcilable alternatives, Americans choose both. The debate that captivated Americans in 1898 decisively shaped world history. Its themes resurface every time we argue about whether to intervene in a foreign conflict. Yet it has faded from memory. Why has the United States intervened so often in foreign lands? How did we reach this point? What drove us to it? Often we seek answers to these questions in the period following World War II. That is the wrong place to look. America’s deep engagement with the world began earlier. The root of it—of everything the United States does and seeks in the world—lies in the debate that is the subject of this book. All Americans, regardless of political perspective, can take inspiration from the titans who faced off in this debate. Their words are amazingly current. Every argument over America’s role in the world grows from this one. It all starts here. Copyright © 2017 by Stephen Kinzer.