Excerpt

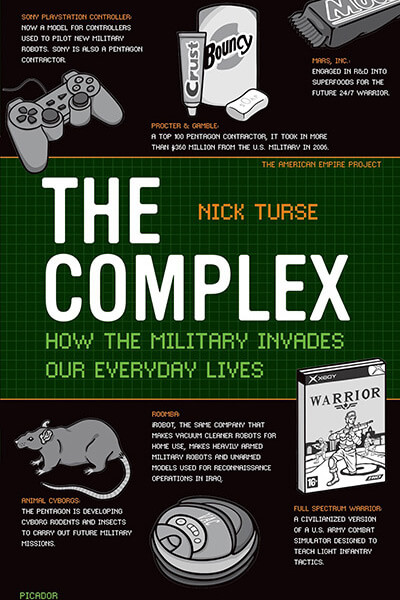

The Complex

How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives

by Nick Turse

Excerpt

The Complex

How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives

by Nick Turse

1

The Iron Triangle

Before the Complex of today came into existence there were the immensely powerful arms manufacturers of Eisenhower’s military-industrial complex. They haven’t exactly gone away. During Eisenhower’s last term in office, from 1957 to 1961, the top five military contractors were General Dynamics, Boeing, Lockheed, General Electric, and North American Aviation. These days, General Electric has slipped slightly (it ranked fourteenth among contractors in 2006), and what’s left of North American Aviation, sold and resold over the years, now exists as part of United Technologies (the ninth-largest contractor in 2006). But even with massive consolidation—a 2003 Pentagon report found that the fifty largest defense contractors of the early 1980s have become today’s top five contractors—the leading players remain largely the same.

In 2002, the massive defense contractors Lockheed Martin, Boeing, and Northrop Grumman ranked one, two, and three among the Pentagon’s defense contractors, taking in $17 billion, $16.6 billion, and $8.7 billion, respectively. Lockheed, Boeing, and Northrop Grumman did it again in 2003 ($21.9, $17.3, and $11.1 billion); 2004 ($20.7, $17.1, and $11.9 billion); 2005 ($19.4, $18.3, and $13.5billion), and 2006 ($26.6, $20.3, and $16.6 billion). General Dynamics ranked fourth in four of the five years—and never lower than fifth.

For decades, these military-industrial powerhouses have produced some of the most sophisticated and deadly weaponry in the U.S. arsenal—from the U-2 spy-plane and Javelin missile (Lockheed) to the B-52 Strato fortress heavy bombers that pounded Indochina (Boeing) to the famed B-2 stealth bomber (Northrop Grumman). Over the years, they have also grown in power and influence, often bending Congress and presidential administrations to their lobbying will and, in some cases, dwarfing the financial clout of various arms of the government itself. For example, from 2000 to 2006, Lockheed Martin received $135.4 billion from the Pentagon—in addition to contracts with the Departments ofHomeland Security, Justice, and Commerce, the Federal AviationAdministration, and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), among others. In 2005, the Bethesda, Maryland–based company’s $25 billion in federal contracts exceeded the total combined budgets of the Departments of Commerce and the Interior, the Small Business Administration, and the U.S. Congress. Peter Singer, an expert on military privatization, uses such examples to suggest that some defense contractors have evolved beyond any conceivable definition of a private business concern. “They’re not really companies, they’re quasi agencies,” he told the New York Times. That’s certainly the case with Lockheed, whose annual sales to U.S. government agencies clocked in at 78 percent of the company’s total business in 2003, 80 percent in 2004, and 85 percent in 2005. In 2006, there was a slight dip to 84 percent, but that didn’t count 13 percent of sales to foreign governments, “including foreign military sales funded, in whole or in part, by the U.S. Government.”

But it isn’t only percentages of sales that link companies like Lockheed so closely to the Pentagon; it’s also their long history of aiding the military in various wars, interventions, incursions, and invasions. The corporate forebears of the firm—which was formed in 1995 when two defense industry stalwarts, Lockheed Corporation and Martin Marietta Corporation, merged—have been working for and with the army and navy since the early years of the twentieth century. And the Complex’s “revolving door,” through which arms manufacturers’ employees and DoD officials routinely passed back and forth between the public and private realm, has continued to turn, creating a familiarity that has cemented the relationship, while offering generous rewards to all involved. (In 1960, at the end of the Eisenhower era, “726 former top ranking military officers were employed by the country’s 100 leading defense contractors.”)

In 2001, to take but one example, Edward C. “Pete” Aldridge Jr. left the defense giant Aerospace Corporation (which took in more than $442 million from the DoD that year) to become the undersecretary of defense (acquisition, technology, and logistics) in Donald Rumsfeld’s Pentagon. Only months into his tenure, Aldridge chose Lockheed Martin to build the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter. In an interview with Ron Insana on CNBC, he announced, “It is the largest acquisition program in the history of the Department of Defense. We’re expecting it to be in excess of $200 billion over the period of the program.” Only minutes later, Aldridge spoke to CNN’s Lou Dobbs, who asked, “How soon will the money start moving from the federal government to Lockheed Martin?” Aldridge replied, “I think Lockheed Martin would like to see some right away . . . as soon as the work starts, they can start billing the government for the work that they’re producing. And so I would expect it’s a matter of a few months away. But very soon.” Lockheed would, indeed, soon be getting paid. By 2006, the estimated cost of the project had already jumped from $200 billion to $276 billion.

In early 2003, despite having previously criticized the program as too expensive, Aldridge approved a $3-billion contract for Lockheed’s controversial F-22 Raptor fighter jet. Then, in March, he announced his retirement, saying, “Now it is time, for personal reasons, to move on to a more relaxed period of my career. I will continue to support the national security interests of this country, albeit in a less direct way.” Within months, Aldridge had been elected to Lockheed Martin’s board of directors, complete with six-figure compensation and company stock, while a former Lockheed man and air force veteran, Michael W. Wynne, took over his post (and went on to become secretary of the air force in 2005).

By 2007, Aldridge was still on the board and held 5,041 units of the corporation’s common stock. The deals he made with Lockheed seem to have paid off handsomely. When Aldridge joined the Pentagon in May 2001, Lockheed’s stock was trading at about $36.62 per share; in 2003, about the time he was elected to Lockheed’s board, it was at $47.52, and by late October 2007 it was trading at $108.61.

Aldridge’s move to Lockheed raised some eyebrows but it’s not clear why, given his long history of using the revolving door.In the 1960s, he had held various posts with Douglas Aircraft Company’s Missile and Space Division. In 1967, the year Douglas merged with McDonnell Aircraft (today, McDonnell Douglas is a wholly owned subsidiary of Boeing), he joined the staff of the assistant secretary of defense for systems analysis and stayed in the post until 1972. He then became a senior manager with LTV Aerospace Corporation before heading back to the government, from 1974 to 1976, to serve as deputy assistant secretary of defense for strategic programs. Dizzyingly enough, in 1977, he was back in the private sector as vice president of the National Policy and Strategic Systems Group for the System Planning Corporation, a major defense contractor. In 1981, Aldridge spun back the other way to become undersecretary of the air force, a position he held until 1986. (From 1981 to 1988, he also served as the director of the U.S. National Reconnaissance Office.) In 1986, he became the secretary of the air force and held the post until December 1988, when he became the president of defense giant McDonnell Douglas’s Electronic Systems Company—the post he held until leaving to join the Aerospace Corporation in 1992.

Aldridge’s revolving-door escapades were far from unique. In 2004, the Project on Government Oversight, an independent nonprofit group that investigates and exposes corruption, reported that, between January 1997 and May 2004, at least 224 senior government officials had taken top positions with the twenty largest military contractors. Lockheed headed the list with thirty-five lobbyists, sixteen executives, and six directors or board members—a total of fifty-seven former senior government officials who had crossed over to the other side. In 2007, for example, in addition to Aldridge, the Lockheed board boasted General Joseph W. Ralston, who had served as vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from 1996 to 2000; James O. Ellis Jr., a navy veteran who had retired from his post as an admiral and commander, U.S. Strategic Command, in July 2004; Admiral James Loy, a former commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard who retired in 2005, after serving as the first deputy secretary of homeland security; Eugene F. Murphy, a Marine Corps veteran and former attorney with the Central Intelligence Agency; and Robert J. Stevens, the chairman, president, and chief executive officer of Lockheed Martin, who had served in the U.S. Marine Corps and is a graduate of the Department of Defense Systems Management College Program Management course.

Under President George W. Bush and his first secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld, the Pentagon was especially well connected to Lockheed. As the author and playwright Richard Cummings noted in Playboy, Powell A. Moore, the assistant secretary of defense for legislative affairs, had, from 1983 to 1998, been a consultant and vice president for legislative affairs for Lockheed. Secretary of the navy and later deputy secretary of defense Gordon England had also worked for Lockheed, as had Peter B. Teets, who became the undersecretary of the air force and director of the National Reconnaissance Office, while Albert Smith, Lockheed’s executive vice president for integrated systems and solutions, was appointed to the Defense Science Board. And the connections didn’t end with the Pentagon. Joe Allbaugh, who moved from being the Bush-Cheney ticket’s national campaign manager to the head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (and brought his college buddy Michael “Brownie, you’re doing a heck of a job” Brown into the agency), was a Lockheed lobbyist. Transportation Secretary Norman Y. Mineta, the lone Democrat in Bush’s cabinet, had been a Lockheed vice president; Vice President Dick Cheney’s son-in-law, Philip J. Perry, was a registered Lockheed lobbyist; and Cheney’s wife, Lynne, had served, until 2001, on Lockheed Martin’s board of directors.

Of course, any discussion of the classic military-industrial complex would be incomplete without the third side of the “iron triangle”: the U.S. Congress. Without the Senate, revolving-door warriors like Aldridge would never get approved for their Pentagon slots, nor would their pet defense programs from past or future defense contractor employers be funded. It’s America’s legislative representatives who pump up the pork in Washington in order to bring home the bacon for their districts (and themselves). Take Aldridge’s baby, the F-22—a fighter designed to counter advanced Soviet aircraft that were never built. Beset by decades of huge cost overruns and embarrassing episodes (such as when a pilot had to be removed from the plane’s defective cockpit using a chain saw) as well as numerous delays and setbacks, the fighter-without-a-foe seemed to be a prime candidate for the chopping block. With real-world costs of each of the 183 planes in the program topping out at $350 million and even powerful Republicans on the SenateArmed Services committee, including Arizona senator John McCain and the committee’s chairman, Virginia senator John W. Warner, lined up against the Lockheed lobby, it looked like the

F-22 might be done for in 2006.

The “powerful F-22 lobby, a combination of the air force, Lockheed Martin, which makes the fighter jet, and their allies in Congress” however were too strong to defeat. As a result, McCain and Warner then attempted to beat back the drive for a multiyear contract for the F-22, which would allow budget cutters a shot at scrapping the program the next year. Prior to the vote, however, Lockheed engaged in a full-scale lobbying effort capped off by an e-mail campaign asking senators to vote “yes” on the proposed Chambliss Amendment, which called for a multiyear deal. In short order, the foes of the F-22 went down in flames. Danielle Brian, the executive director of the Project on Government Oversight, explained, “The F-22 lobby is an extraordinary juggernaut and they fought to the death on this one.” She observed, “It is astonishing in that the lobby can take on the most powerful in Washington, including the president, and win.”

The Chambliss Amendment was named for Saxby Chambliss, a Republican senator from Georgia whose district just happened to include an F-22 assembly plant. And Chambliss wasn’t alone in being locked in to Lockheed. The e-mail campaign reminded many senators where their bread was buttered. In fact, spreading the wealth is one prime way Lockheed does business. In addition to its Marietta, Georgia, plant, Lockheed produces the F-22 Raptor at facilities in Palmdale, California; Meridian, Mississippi; Fort Worth, Texas; and even at a Boeing plant in Seattle, Washington. For added insurance, Lockheed parcels out production of the parts and subsystems in truly national fashion. In all, Lockheed boasts that one thousand suppliers in forty-two states play a role in equipping the F-22.

Lockheed has spread the wealth on other projects as well. In late December 2006, Lockheed divided up $376 million of work on a new Patriot missile system contract between facilities in Grand Prairie, Texas; Lufkin, Texas; Camden, Arkansas; Huntsville, Alabama; Chelmsford, Massachusetts; Clearwater, Florida; and Atlanta, Georgia. In early January 2007, the corporation divvied up $28.5 million of work on the Acoustic Rapid Commercial Off-the-Shelf Insertion sonar system among plants in Manassas, Virginia; Portsmouth, Rhode Island; Oldsmar, Florida; Chantilly, Virginia; Syracuse, New York; Chelmsford, Massachusetts; St. Louis, Missouri; and Houston, Texas.

The Chambliss Amendment was passed on the premise that a multiyear deal, which would lock the government in for bulk purchases of F-22s, would be a cost-saving mechanism—even though both the Government Accountability Office and the Congressional Research Service said otherwise. Chambliss claimed to have based his assessment on an “independent” analysis by the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a federally funded nonprofit research center that focuses on technical aspects of national security issues. However, it was later revealed by the Defense Department’s inspector general that the then head of the IDA, retired navy admiral Dennis C. Blair, had “violated conflict-of-interest rules when he failed to distance himself from two reports that could have affected companies in which he had a financial interest.” Blair, it turned out, sat on the boards of two of those one thousand F-22 subcontractors, which made electronic components that were sold to other F-22 subcontractors.

While jobs in home districts and conflicts of interest surely played key roles in preserving the plane, the F-22 and other pork-laden weapons systems are regularly enabled by a basic practice that makes the “iron triangle” what it is: Washington-style payoffs. As Matt Taibbi noted in Rolling Stone, “Chambliss’ amendment passed 70–28, with wide bipartisan support. Most all of the senators who voted for the bill, including Democrats like Joe Lieberman, Chuck Schumer and Daniel Inouye, had received generous campaign contributions from Lockheed Martin, the maker of the F-22, and from subcontractors like Pratt and Whitney.” Such efforts are standard operating procedure for Lockheed, which spent more than $59 million on campaign contributions and lobbying between 2000 and 2006, and—according to OpenSecrets.org, a Web site sponsored bythe Center for Responsive Politics that analyzes filings from the Federal Election Commission—gave 59 percent of its money to Republicans and 41 percent to Democrats between 1990 and 2006.

But don’t feel bad for the Democrats. The columnist Derrick Z. Jackson, writing in the Boston Globe in 2007, noted that among the ten senators who received the most money in campaign contributions from defense contractors in the 2006 election cycle were the following six: Democrats Edward M. Kennedy of Massachusetts, Hillary Clinton of New York, Christopher Dodd of Connecticut, Dianne Feinstein of California, Bill Nelson of Florida, and Democrat-turned-independent Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, who “collected 60 percent of the $1.4 million the industry lavished among the top 10.” For what did they deserve these riches? Clinton, notably, was found to have slipped twenty-six earmarks—line items (generally pork-barrel projects) inserted into huge spending bills to direct funds to a specific project without any review—into the defense budget. That was the second highest among senators. As for Kennedy, the Globe found that he “slid $100 million into the 2008 defense authorization bill for a General Electric fighter engine that the Air Force said it did not need.”

The classic iron triangle—Congress, big military contractors (like Lockheed, Boeing, Northrop Grumman, the General Dynamics Corporation, Raytheon, Halliburton, the Bechtel Corporation, and BAE Systems) and the Pentagon—has always formed the essential core of the military-industrial complex. These firms still reign supreme as the primary weapons-producing “merchants of death,” but huge arms dealers, like Lockheed Martin and Boeing, are now only a portion of the story. While they may still rake in the largest single sums of any Pentagon contractors, their total take—Lockheed’s was number one in 2006 with $26,619,693,002, or 9.02 percent of all contracts—is dwarfed by the combined totals of the restof the DoD’s contractors. These include big-name companies, small firms, and organizations you might never suspect of being on the military dole, ranging from Columbia TriStar Films and Twentieth Century Fox to Velda Farms (“a leader in the dairy industry for over 50 years”) and from the National Vitamin Company of Porterville, California, to the American Meat Institute (“the nation’s oldest and largest meat and poultry trade association”) and the American Medical Association (which is dedicated to promoting “the betterment of public health”). These entities now form the bulk of the Complex, turning the iron triangle into a collection of “iron myriagons” (ten-thousand-sided polygons).

Copyright © 2008 by Nick Turse