Excerpt

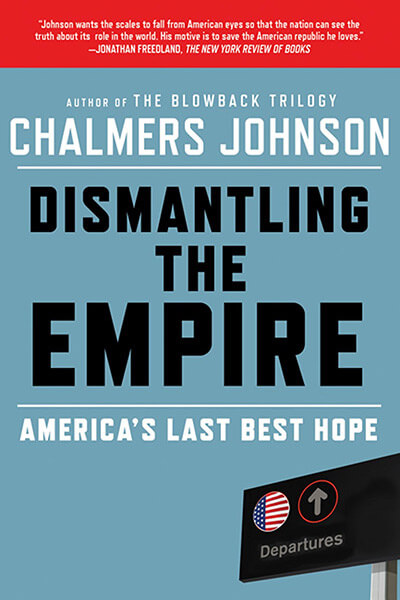

Dismantling the Empire

America's Last Best Hope

by Chalmers Johnson

Excerpt

Dismantling the Empire

America's Last Best Hope

by Chalmers Johnson

Introduction

The Suicide Option

During the last years of the Clinton administration I was in my mid-sixties, retired from teaching Asian international relations at the University of California and deeply bored by my specialty, Japanese politics. It seemed that Japan would continue forever as a docile satellite of the United States, a safe place to park tens of thousands of American troops, as well as ships and aircraft, all ready to assert American hegemony over the entire Pacific region. I was then in the process of rethinking my research and determining where I should go next.

At the time, one aspect of the Clinton administration especially worried me. In the aftermath of the breakup and disappearance of the Soviet Union, U.S. officials seemed unbearably complacent about America’s global ascendancy. They were visibly bathed in a glow of post–Cold War triumphalism. It was hard to avoid their high-decibel assertions that our country was “unique” in history, their insistence that we were now, and for the imaginable future, the “lone superpower” or, in the words of Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, “the indispensable nation.” The implication was that we would be so for an eternity. If ever there was a self-satisfied country that seemed headed for a rude awakening, it was the United States.

I became concerned as well that we were taking for granted the goodwill of so many nations, even as we incautiously ran up a tab of insults to the rest of the world. What I couldn’t quite imagine was that President Clinton’s arrogance and his administration’s risk taking—the 1998 cruise missile attack on the al-Shifa pharmaceutical plant in Khartoum, Sudan, for instance, or the 1999 bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, Serbia, during the Kosovo war—might presage an existential crisis for the nation. Our stance toward the rest of the world certainly seemed reckless to me, but not in itself of overwhelming significance. We were, after all, the world’s richest nation, even if we were delusional in assuming that our wealth would be a permanent condition. We were also finally at peace (more or less) after a long period, covering much of the twentieth century, in which we had been engaged in costly, deadly wars.

As I quietly began to worry, it crossed my mind that we in the United States had long taken all of Asia for granted, despite the fact that we had fought three wars there, only one of which we had won. My fears grew that the imperial tab we were running up would come due sooner than any of us had expected, and that payment might be sought in ways both unexpected and deeply unnerving. In this mood, I began to write a book of analysis that was also meant as a warning, and for a title I drew on a term of CIA tradecraft. I called it Blowback.

The book’s reception on publication in 2000 might serve as a reasonable gauge of the overconfident mood of the country. It was generally ignored and, where noted and commented upon, rejected as the oddball thoughts of a formerly eminent Japan specialist. I was therefore less shocked than most when, as the Clinton years ended, we Americans made a serious mistake that helped turn what passed for fringe prophecy into stark reality. We let George W. Bush take the White House.

He was a man superficially well enough qualified to be president. The governor of a populous state, he had also been the recipient of one of the best—or, in any case, most expensive—educations available to an American. Yale College and Harvard Business School might have seemed like a guarantee against a sophomoric ignoramus occupying the highest office in the land, but contrary to most expectations that was precisely what we got. The American public did not actually elect him, of course. He was, in the end, appointed to the highest office in the land by a conservative cabal of Supreme Court justices in what certainly qualified as one of the most bizarre moments in the history of American politics.

During his eight reckless years as president, Bush, his vice president Dick Cheney, his secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld, and the other neoconservative and right-wing officials he appointed, war-lovers all, drove the country as close to the precipice as was humanly possible. After the attacks of 9/11, he would have been wise to treat al-Qaeda as the criminal organization it was. Instead, he launched two wars of aggression in close succession against Iraq and Afghanistan. The irony was that had he done absolutely nothing, the political situations in both countries would likely have resolved themselves, given time, in ways tolerable for us and our allies based on the constellation of forces at work in each place. Instead, his policies entrenched Shia Muslims in Iraq, repeated all the mistakes of other foreign invaders—particularly the British and more recently the Russians—in Afghanistan, and enhanced the power of Iran in the Persian Gulf region.

As a result of his ill-informed and bungling strategic moves, President Bush left our armed forces seriously depleted, with worn-out equipment, badly misused human resources, and staggering medical (and thus financial) obligations to thousands of young Americans suffering from disabling wounds, including those inflicted on their minds. Meanwhile, our high command, which went into Afghanistan and Iraq stuck in the land war doctrines of World War II but filled with dreamy, high-tech, “netcentric” fantasies, is now mired in the failed counterinsurgency doctrine of the Vietnam era. That’s what evidently passes for progress in the Pentagon these days. Its officials still have hardly a clue as to how to deal with nonstate actors like al-Qaeda.

At the same time, the Bush administration paved the way for, and then presided over, a close to catastrophic economic and financial collapse that skirted national and international insolvency. Fueled by huge tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans, profligate spending on two wars (as well as future wars and the weaponry to fight them), the appointment of Republican ideologues to critical positions of trust, and accounting and management practices that exacerbated just about every other problem, the Bush administration plunged us into the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.

As if these failures weren’t bad enough, during Bush’s tenure the armed forces were authorized to torture Muslims captured virtually anywhere on earth; the Department of Justice turned a blind eye to the clandestine electronic surveillance of the general public; and the Central Intelligence Agency was given carte blanche to kidnap terror suspects in other countries and transfer them to regimes where they could be interrogated under torture, as well as to assassinate supposed terror suspects just about anywhere on the planet. From Afghanistan and Iraq to Lithuania, Thailand, and Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, the United States set up an offshore system of (in)justice, including “black sites” (secret CIA prisons) that put many of its most outrageous acts beyond oversight or the reach of the law—any law. In the meantime, the United States also withdrew from many important international treaties, including the one banning the production of antiballistic missiles.

The history books will certainly record that George W. Bush was likely the single worst president in the history of the American republic. Nonetheless, they will also point out that he merely accelerated trends long under way, particularly our devotion to militarism and our dependence on the military-industrial complex.

In 2008, faced with a truly dysfunctional government, the American people unexpectedly demonstrated that they got the message. The presidential candidacy of Barack Obama reignited a long-dormant idealism, particularly among those who believed, on the basis of their own lives, that the political system had been rigged against them. The national outpouring of enthusiasm for this African American presidential candidate led many around the world to believe that the American people were ready to abandon their infatuation with imperialism. They assumed that we were exhibiting a desire for genuine reform before the trends of the Clinton-Bush years became irreversible.

During his campaign Barack Obama promised to close our extrajudicial detention camp at Guantánamo Bay; restore legally sanctioned practices, particularly within the Department of Justice; provide nearly all citizens with health insurance and other life support systems that are routine in most advanced industrial democracies; take global warming seriously; and implement any number of laws that were being honored only in the breach, including those protecting personal privacy. Obama’s proposed reform program was massive, long overdue, and popularly welcomed.

Conspicuously absent from this lengthy agenda, however, was one significant sector of American life. Only those of us who had long watched this area noted Obama’s silence and were alarmed for what it suggested about his future presidency. This omission concerned the massive apparatus that enables what I have called our global “empire of bases” to exist and function. In the campaign, he said little about the armed forces (other than that he would like to expand the Army and Marines), the military-industrial complex, the Pentagon’s failure to account properly for the vast sums it spends, the growing clandestine role of our proliferating intelligence services, or the subcontracting of extremely sensitive national security tasks to the private sector.

Given the degree to which, as this book emphasizes, the Pentagon and the powerful forces that surround it have played such a crucial role in leading this country to the edge, this campaign omission was anything but auspicious. It is undoubtedly true that a presidential candidate determined to take on these forces might have had a difficult time cutting the Pentagon, the “intelligence community,” and the military-industrial complex down to size. Unfortunately, Obama did not even try. The evidence already suggests that huge vested interests in the status quo blocked this president from the start—and, no less important, that when it came to our national security state and our global imperial presence he acquiesced.

I have written elsewhere that on his first day in office every president is given a highly secret briefing about the clandestine powers at his disposal and that no president has ever failed to use them. It is increasingly clear that while pursuing his agenda in other areas, Obama, who made James Jones, a retired Marine Corps commandant, the head of his National Security Council and Robert Gates, a former Cold War CIA director and holdover from the Bush years, his secretary of defense, is going along with what the militarist establishment in Washington recommends, while offering little in the way of resistance. As commander in chief, he must be supportive of our armed forces, but nothing obliges him to take pride in American imperialism or to “finish the job” that George Bush began in Afghanistan, as he seems intent on doing.

The essays in this volume were, for the most part, written over the last three years. Although some look back at the recent past, most focus on our limited resources for continuing to behave like an empire and what the likely outcome will be. We are not, of course, the first country to face the choice between republic and empire, nor the first to have our imperial dreams stretch our means to the breaking point and threaten our future. But this book suggests that among the alternatives available to us as a nation, we are choosing what I call the suicide option. It also suggests that it might not have to be this way, that we still could move in a different direction.

We could begin to dismantle our empire of bases. We could, to offer but one example, simply close Futenma, the enormous Marine Corps base on Okinawa much disliked by the new Japanese government that took office in Japan in 2009. Instead, we continue to try to browbeat the Japanese into acting as our docile satellite by forcing them to pay for the transfer of our Marines either to the island of Guam (which can’t support such a base either) or to an environmentally sensitive area elsewhere on Okinawa.

Seldom has an incoming president been given greater benefit of the doubt than President-elect Obama. When, for no apparent good reason, he decided to retain President Bush’s top military appointment in our war zones, CENTCOM commander General David Petraeus, hang on to Secretary of Defense Gates, and later reinforce the large American expeditionary force already fighting in Afghanistan, Republicans spoke of continuity and some Democrats explained it as a brilliant ploy to shift blame for an all but certain American defeat to Republican holdovers. But Obama certainly had other options. For secretary of defense he might have turned to someone like retired Army lieutenant colonel Andrew Bacevich, author of the best-selling book The Limits of Power. Nor were generals Petraeus and Afghan war commander Stanley McChrystal, who had previously run counterterror operations for Bush in both Iraq and Afghanistan, inevitable choices. But these were the people Obama appointed. They, in turn, have devised policies that have allowed him to continue the war in Afghanistan in the face of grave public doubts, just as they did in Iraq for Obama’s predecessor.

Whether or not becoming a war president is what Obama truly intended, the greatest obstacle to his war policies is that the United States cannot afford them. The federal deficit was already spiraling out of control before the Great Recession of 2008. Since then, the government has only gone more deeply into debt to prevent the collapse of critical financial institutions as well as the housing industry. It is not clear that Obama’s measures to overcome the Great Recession will do anything more than take resources away from necessary projects and leave the country that much closer to bankruptcy. It is absolutely certain that the estimated trillion dollars a year spent on the defense establishment will make it almost impossible for the United States to avoid the ultimate limit on imperialism: overstretch and insolvency.

In December 2009, the United States had its best and perhaps last chance to avoid the suicide option. After a three-month review of our activities in Afghanistan, when he might have found a way to disengage, Obama instead decided to escalate—at a cost he estimated, in a speech at West Point explaining his decision, at $30 billion per year but certain to go far higher, not to mention the costs in human lives—American, allied, and Afghan. Although by then a majority of our population believed we had done everything we could for a poor central Asian country led by a hopelessly corrupt government, President Obama chose to continue our imperialist project. As Hamlet said, “It is not, nor it cannot come to good.”

None of this was inevitable, although it may have been unavoidable given the hubris and arrogance of our national leadership.

Copyright © 2010 by Chalmers Johnson