Excerpt

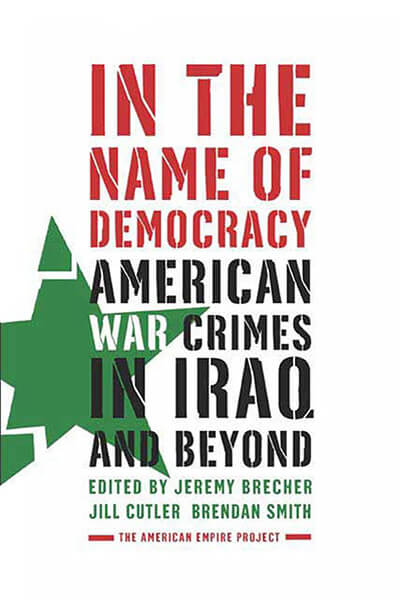

In the Name of Democracy

American War Crimes in Iraq and Beyond

by Jeremy Brecher

Excerpt

In the Name of Democracy

American War Crimes in Iraq and Beyond

by Jeremy Brecher

Introduction

The ultimate step in avoiding periodic wars, which are inevitable in a system of international lawlessness, is to make statesmen responsible to law.

—Opening statement of Justice Robert Jackson, chief American prosecutor at the Nuremberg Tribunal, 1945

It is a big mistake for us to grant any validity to international law even when it may seem in our short-term interest to do so—because, over the long term, the goal of those who think that international law really means anything are those who want to constrict the United States.

—John Bolton, Under Secretary of State, nominated 2005 for American ambassador to the United Nations

Brandon Hughey was a private at Fort Hood when he discovered that his army unit was about to be sent to Iraq. The eighteen-year-old from San Angelo, Texas, was desperate—not because he was afraid to go to war but because he was convinced that the Iraq war was immoral. He considered solving the problem by taking his own life. Instead, he got in a car and drove to Canada. He explained, “I would fight in an act of defense, if my home and family were in danger. But Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction. They barely had an army left, and [UN Secretary-General] Kofi Annan actually said [attacking Iraq was] a violation of the UN charter. It’s nothing more than an act of aggression. You can’t go along with a criminal activity just because others are doing it.”

If, as the Bush administration has maintained, the United States is fighting in Iraq to protect itself from terrorism, free the people of Iraq from tyranny, enforce international law, and bring peace and democracy to the Middle East, then war resisters like Brandon Hughey appear deluded if not cowardly and criminal.

But what if Private Hughey is right? What if the U.S. operation in Iraq is “nothing more than an act of aggression”? What if it indeed constitutes “criminal activity”? What, then, is the culpability of President George W. Bush, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and other top U.S. officials? And what is the responsibility of ordinary Americans?

Until recently, the possibility that top U.S. officials were responsible for war crimes seemed to many Americans nothing but the invidious allegations of a few knee-jerk anti-Americans. But as more and more suppressed photos and documents have been disclosed, and as more and more eyewitness accounts from prisons and battlefields have appeared in the media, Americans are undergoing an agonizing reappraisal of the Iraq war and the broader war on terror of which it is allegedly a part.

The Washington Post, once an avid supporter of the U.S. attack on Iraq, headlined an end-of-2004 editorial “War Crimes.” It addressed the actions not of Saddam Hussein or Slobodan Miloˇsevi´c, but rather of U.S. defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld: “Since the publication of photographs of abuse at Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison in the spring the administration’s whitewashers—led by Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld—have contended that the crimes were carried out by a few low-ranking reservists.” These whitewashers have similarly contended that “no torture occurred at the Guantánamo Bay prison.” But “New documents establish beyond any doubt that every part of this cover story is false.” The documents “confirm that interrogators at Guantánamo believed they were following orders from Mr. Rumsfeld.” The Post charges that violations of human rights “appear to be ongoing in Guantánamo, Iraq and Afghanistan.” And “the appalling truth is that there has been no remedy for the documented torture and killing of foreign prisoners by this American government.”

The purpose of this book is to help Americans face up to what our country has been doing in Iraq and more broadly in the war on terror—and to face up to the responsibilities those realities entail for us. It explores the evidence for U.S. war crimes. It addresses the question of who is responsible for them. It examines the plans to continue them. It opens up the historical, legal, and moral questions they pose. It presents the story of those who have refused to participate in them. Finally, it looks at the responsibility of ordinary citizens to halt war crimes and how that responsibility might be met.

what are war crimes?

There are many bad things in the world, but nearly all countries in the world have joined to single out certain acts as war crimes—crimes so heinous that they are offenses not just against their immediate victims but against all of humanity. As a U.S. federal judge said of one type of war criminal, “The torturer, like the pirate of old, has become hostis humanis generis, the enemy of mankind.”

Several overlapping strands have come together in the contemporary popular concept of war crimes. One, with roots in many cultures around the world, including the “just war” doctrines of medieval Europe, is that armed attack on another country is a crime. As the Nuremberg Tribunal put it, “To initiate a war of aggression” is “the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.” The UN Charter provided that “all members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.” Violations of this principle are crimes against peace.

A second strand is humanitarian law, which protects combatants and civilians from unnecessary harm during war. In 1863, U.S. president Abraham Lincoln promulgated the Lieber Code defining protections for civilians and prisoners of war. The next year a number of countries agreed to the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field.1 Diplomatic conferences in 1899 and 1907 produced the “Law of the Hague,” which prohibited attacks on undefended towns, use of arms designed to cause unnecessary suffering, poison weapons, collective penalties, and pillage.2

The devastation associated with World War II led to the recognition of a new category of international crimes, crimes against humanity, which involved acts of violence against a persecuted group in either war or peacetime. The Nuremberg Charter defined these acts as “murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against civilian populations, before or during the war; or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated.” The definition of crimes against humanity has since been expanded to include rape and torture.

These three strands came together after World War II in the Nuremberg and Tokyo war crimes trials. Crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity have come to be summed up as war crimes.3 War crimes were codified in the four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and have been further developed in subsequent protocols and agreements.

By agreeing to the UN Charter, the Geneva Conventions, and other such treaties, nations agreed to bind themselves to limitations on their sovereign prerogatives. But as Lisa Hajjar explains in her contribution to the present volume: “Enforcement depended on the willingness of individual states to conform to the laws they signed, and on the system of states to act against those that did not. While some states instituted domestic reforms and pursued foreign policies in keeping with their international obligations, most refused to regard human rights and humanitarian laws as binding.” Despite Nuremberg, ours has been “an age of impunity.”

But as Richard Falk writes in this book, the 1990s saw “a dramatic revival of the idea that neither states nor their leaders were above the law with respect to war making and crimes against humanity.” International tribunals tried war crimes in the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone. The International Criminal Court was created—despite massive opposition from the Bush administration.4 Henry Kissinger—himself a target of that revival—wrote in alarm in 2001 that “in less than a decade an unprecedented movement has emerged to submit international politics to judicial procedures” and has “spread with extraordinary speed.”5 War crimes prosecution, once a dimming historical memory, became a living contemporary presence.

War crimes have several characteristics that make them different from other crimes. War criminals are subject to universal jurisdiction, meaning that they can be tried not just in their own country but anywhere in the world. War crimes are likely to be the acts of high government officials, and such officials are likely to be in a position to prevent the courts of their own country from bringing them to justice. While international law prefers that each country deal with its own war criminals, international tribunals and the courts of other nations have been given authority to try war crimes cases where national courts fail to act.

Many laws, such as the laws against killing people, are suspended in times of war. But the law of war crimes applies even under conditions of emergency.6 It is designed for conditions of war; absence of normal legality is no defense for war crimes. The Convention Against Torture, for example, provides that “no exceptional circumstances whatsoever, whether a state of war or a threat or war, internal political instability or any other public emergency, may be invoked as a justification of torture.”7

The prohibition on war crimes is absolute, not relative. U.S. Justice Robert Jackson proclaimed at Nuremberg, “No grievances or policies will justify resort to aggressive war. It is utterly renounced and condemned as an instrument of policy.”8 The same applies to other war crimes as well. The war crimes of one’s opponents are no justification for one’s own.

Charges that opponents have committed war crimes have become common currency of international conflict. But war criminal is more than an epithet. Today there is a body of law that is clearly enough formulated and widely enough accepted to be interpreted by courts based on procedures similar to those used for judging other crimes. Those are the standards by which allegations of American war crimes must be judged.

the evidence

Part I summarizes the rapidly accumulating evidence of U.S. war crimes. This evidence comes from official government investigations; official documents released under court order; information leaked by participants and whistle-blowers; eyewitness accounts; and victims’ experiences.

There are three sets of questions regarding possible U.S. war crimes in Iraq. The first set of questions concerns the legality of the U.S. attack on Iraq under international law. Secretary-General Kofi Annan of the United Nations stated shortly before the attack that the UN Charter is “very clear on the circumstances under which force can be used. If the U.S. and others were to go outside the Council and take military action, it would not be in conformity with the charter.”9 He subsequently stated that the invasion of Iraq was “not in conformity with the UN Charter, from our point of view, and from the Charter point of view, it was illegal.” The U.S. admission that Iraq had no weapons of mass destruction, and the growing evidence that the United States fabricated the evidence on which that charge was based, has provided added weight to Annan’s view.

The second set of questions involves the possible illegality of the U.S. occupation of Iraq and its conduct. The seriousness of such questions was recently underlined by the warning of Louise Arbour, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, that those guilty of violations of international humanitarian rights laws—including deliberate targeting of civilians, indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks, killing of injured persons, and the use of human shields—must be brought to justice, “be they members of the Multinational Force or insurgents.”

The military technology the United States is using in Iraq, such as cluster bombs and depleted uranium, may be illegal in itself. Under Article 85 of the Geneva Conventions it is a war crime to launch “an indiscriminate attack affecting the civilian population in the knowledge that such an attack will cause an excessive loss of life or injury to civilians.” A UN weapons commission described cluster bombs as “weapons of indiscriminate effects.” A reporter for the Mirror (United Kingdom)10 wrote from a hospital in Hillah, “Among the 168 patients I counted, not one was being treated for bullet wounds. All of them, men, women, children, bore the wounds of bomb shrapnel. It peppered their bodies. Blackened their skin. Smashed heads. Tore limbs. A doctor reported that ‘All the injuries you see were caused by cluster bombs’ . . . The majority of the victims were children who died because they were outside.”

The third set of questions has to do with the torture and abuse of prisoners in U.S. custody. This has been a huge but unresolved issue since it was first indelibly engraved in the public mind by the photos from Abu Ghraib prison. Cascading disclosures have revealed that torture and other forms of prisoner abuse have been endemic not only in Iraq but in Afghanistan, Guantánamo, and many other U.S. operations around the world.

culpability

One of the most important principles established at Nuremberg is that individuals are responsible for their own actions, even if they were obeying orders, and that those in a position to give orders are responsible for the actions of those under them. “Complicity in the commission of a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity” is “a crime under international law.” Furthermore, “the fact that a person who committed an act which constitutes a crime under international law acted as Head of State or responsible Government official does not relieve him of responsibility under international law.”

In those few instances where the Bush administration has admitted that wrongdoing may have occurred in connection with Iraq and the war on terror, it has consistently blamed low-level personnel and denied its own responsibility. But there are growing indications that, from the initial manipulation of evidence to justify the attack on Iraq to the latest cover-up of memos justifying torture, the highest levels of the Bush administration have been involved. Part II presents evidence that the trail of responsibility for the policies that led to such actions runs to the highest levels of the Pentagon and the door of the Oval Office.

As International Herald Tribune columnist William Pfaff wrote, “Proposals to authorize torture were circulating even before there was anyone to torture. Days after the Sept. 11 attacks, the administration made it known that the United States was no longer bound by international treaties, or by American law and established U.S. military standards concerning torture and the treatment of prisoners.”11 In January 2002, White House counsel Alberto Gonzales advised the president that if he “simply declared ‘detainees’ in Afghanistan outside the protection of the Geneva conventions, the 1996 U.S. War Crimes Act—which carries a possible death penalty for Geneva violations—would not apply.” Later a legal task force from the Department of Defense concluded that the president, as commander in chief, had the authority “to approve any technique needed to protect the nation’s security.” As Pfaff observed, “Subsequent legal memos to civilian officials in the White House and Pentagon dwelt in morbid detail on permitted torture techniques, for practical purposes concluding that anything was permitted that did not (deliberately) kill the victim.”

The Bush administration has systematically tried to block accountability for war crimes. It has refused to join the International Criminal Court and has pressured countries around the world to exempt it from prosecution. It pressured Belgium to repeal the law granting Belgian courts universal jurisdiction to try international law cases. As the New York Times put it, the Bush administration “drags its feet on public disclosure, stonewalls Congressional requests for documents and suppressed the results of internal investigations.”12

The United States has promoted war crimes prosecutions starting with the Nuremberg trials after World War II and continuing to the recent trials in Rwanda and the current trials of Slobodan Miloˇsevi´c and Saddam Hussein. These trials have all emphasized the accountability of top officials for acts committed under their authority. Is there any reason the same standard should not be applied to the top officials in the Bush administration?

future war crimes

Part III indicates that the problem of U.S. war crimes is not simply one of correcting misdeeds of the past. The Bush administration’s actions in Iraq are part of a broader set of policies it refers to as the war on terror. These policies lay the groundwork and provide the justification for U.S. war crimes to continue in the future.

The Bush administration’s security doctrine, as articulated in the 2002 National Security Strategy, declared a war on terror “of uncertain duration.” It enunciated a doctrine of preventive war in which “the United States will act against such emerging threats before they are fully formed.” It “will not hesitate to act alone, if necessary, to exercise our right of self defense by acting preemptively.” As Senator Robert Byrd commented, “Under this strategy, the President lays claim to an expansive power to use our military to strike other nations first, even if we have not been threatened or provoked.”

The investigative journalist Seymour Hersh recently discovered that President Bush had signed “a series of findings and executive orders authorizing secret commando groups and other Special Forces units to conduct covert operations against suspected terrorist targets in as many as ten nations.” Threats against Iran, Syria, North Korea, and other countries are repeatedly uttered by the Bush administration. Officials in the Department of Defense told the New York Times they are making plans for “fighting for intelligence,” that is, commencing combat operations chiefly to obtain intelligence. U.S. officials are making plans to hold captives for their lifetimes without trial in countries around the world. And they are planning to create assassination teams—modeled on the “death squads” of El Salvador—to eliminate their opponents in Iraq.

facing the implications

The possibility that high U.S. officials may be guilty of war crimes and may be preparing to commit more raises questions that few Americans have yet faced. These questions go far beyond technical legal matters to the broadest concerns of international security, democratic government, morality, and personal responsibility. Part IV presents perspectives from a variety of disciplines and political viewpoints designed to help us address those questions.

The UN Charter, the Geneva Conventions, and the principles of international law, while all too often violated, have provided some basis for international peace and security. What is the likely result of following the advice of the Bush administration’s John Bolton that it is “a big mistake for us to grant any validity to international law”? Is it likely to be greater freedom and security, or an unending war of all against all? Are the American people—not to mention the people of the world—ready to abandon the international rule of law and return to what Justice Jackson called “a system of international lawlessness”?

The Bush administration has made extraordinary claims regarding the authority of the president to act without legal restraint. This questions the very idea of the United States as a democracy governed by a constitution. As Sanford Levinson writes in this volume: “The debate about torture is only one relatively small part of a far more profound debate that we should be having. Do ‘We the People,’ the ostensible sovereigns within the American system of government, accept the vision of the American president articulated by the Bush administration? And if we do, what, then, is left of the vaunted vision of the rule of law that the United States ostensibly exemplifies?”

The United States has vast power, but it includes only 5 percent of the world’s people. If its leaders engage in war crimes with impunity, what is apt to happen to its relations with the rest of the world’s peoples and governments? Can it gain cooperation to meet its national objectives and the needs of its people? Or will it face growing scorn and isolation?

And what about the moral questions raised by war crimes? Is there a limit to the behavior we are prepared to accept? As Bob Herbert asks in a recent article, “As a nation, does the United States have a conscience? Or is anything and everything O.K. in post–9/11 America? If torture and denial of due process are O.K., why not murder? . . . Where is the line that we, as a nation, dare not cross?”13

resisters

Some of the most difficult issues are faced by those in the military and the government who may be directly complicit in war crimes. Some have said no to participation in the war in Iraq and the cover-up of related criminal activity. Part V presents statements by, interviews with, and articles about military and civilian resisters.

Specialist Jeremy Hinzman of Rapid City, South Dakota, joined the Eighty-second Airborne as a paratrooper in 2001. He wanted a career in the military and did a stint in Afghanistan. Then he was ordered to Iraq. “I was told in basic training that, if I’m given an illegal or immoral order, it is my duty to disobey it. And I feel that invading and occupying Iraq is an illegal and immoral thing to do.”

In September 2004, Stephen Funk, a marine reservist of Filipino and Native American origin, was tried for refusing to fight in Iraq. “In the face of this unjust war based on deception by our leaders, I could not remain silent. In my mind that would have been true cowardice . . . I spoke out so that others in the military would realize that they also have a choice and a duty to resist immoral and illegitimate orders.”

In December 2004, the Hispanic sailor Pablo Paredes, wearing a T-shirt reading, “Like a cabinet member, I resign,” refused to board his Iraq-bound ship in San Diego Harbor. At his court-martial, Paredes said, “I am convinced that the current War on Iraq is illegal.” As a member of the armed forces, “beyond having a duty to my chain of command and my President, I have a higher duty to my conscience and to the supreme Law of the land. Both of these higher duties dictate that I must not participate in any way, hands on or indirect, in the current Aggression that has been unleashed on Iraq. . . . I am guilty of believing that as a service member I have a duty to refuse to participate in this War because it is illegal.” Astonishingly, the military judge, Lt. Cmdr. Robert Klant, accepted Paredes’ war crimes defense and refused to send him to jail. The government prosecutor’s case was so weak that Klant declared ironically, “I believe the government has just successfully proved that any seaman recruit has reasonable cause to believe that the wars in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and Iraq were illegal.”14

Resistance has also taken the form of unauthorized leaking of secret information about U.S. war crimes by military and government whistle-blowers. For example, in May 2003 a group of military lawyers went to visit a leader of the Association of the Bar of New York. They told him of the justifications for torture and other violations of the Geneva Conventions being propounded at high levels of government. The resulting report was one of the first public disclosures of the role of high government policymakers in torture and prisoner abuse.

These various kinds of resisters have taken a risk and often paid a price for their actions. Those actions may contribute to a greater or lesser degree to bringing war crimes to a halt. Beyond that, they pose to all Americans the question of what their own responsibility to halt war crimes may be.

halting war crimes

Under the principles established by the Nuremberg and Tokyo war crimes tribunals, those in a position to give orders are responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity conducted under their authority. But responsibility does not end there. The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal declared, “Anyone with knowledge of illegal activity and an opportunity to do something about it is a potential criminal under international law unless the person takes affirmative measures to prevent the commission of the crimes.”15 Part VI explores the responsibility of ordinary citizens and what “affirmative measures” they might take to bring war crimes to a halt.

Crimes are ordinarily dealt with by the institutions of law enforcement. But those institutions are largely in the hands of people who may be complicit in the very crimes that need to be investigated. Can they be held accountable? Or can war criminals forever act with impunity?

The problem of a government that is ostensibly democratically elected but that defies actual accountability is one that citizens in many countries have faced at one time or another. We can take inspiration from the way citizens from Serbia to the Philippines and from Chile to Ukraine have utilized “people power” to block illegal action and force accountability on their leaders. We can similarly take inspiration from resistance to illegitimate authority in our own country from the American Revolution to the Watergate investigations that ultimately brought the Nixon administration to account for its criminal abuse of power.

Part VI examines the failure of established institutional structures to restrain criminality on the part of the Bush administration. It considers how the processes of law enforcement could be revitalized to address war crimes. It also examines institutional forms that could be invoked, such as the U.S. War Crimes Act of 1996, congressional investigatory powers, a 9/11–style independent commission, and a special prosecutor, to establish accountability for these crimes. It describes the role that military and governmental personnel and ordinary citizens can play in catalyzing change by refusing to obey illegal “law.” It examines efforts to encourage and support such resistance. And it emphasizes the role of civil society and ordinary citizens in bringing American war crimes to a halt.

war crimes and democracy

If war crimes are being committed, they are being committed in the name of democracy. Their ostensible purpose is to extend democracy throughout the world. They are committed by a country that proudly proclaims itself the world’s greatest democracy.

Such acts in Iraq and elsewhere represent, on the contrary, the subversion of democracy. They reflect the imposition by violence and brutality of a rule that is not freely chosen.

Such acts also represent a subversion of democracy at home. They represent a presidency that has denied all accountability to Congress, courts, or international institutions. As Elizabeth Holtzman puts it in her contribution to this volume: “The claim that the President . . . is above the law strikes at the very heart of our democracy. It was the centerpiece of President Richard Nixon’s defense in Watergate—a defense that was rejected by the courts and lay at the foundation of the articles of impeachment voted against him by the House Judiciary Committee.” It denies the constitutional constraints that have made the United States a government under law. It subverts democracy in the name of democracy.

War crimes represent the defiance not only of international but also of U.S. law. The effort to halt them is at once a movement for peace and a struggle for democracy.

Note: Wherever possible we have indicated both text and Internet sources for the full original documents we have excerpted.

Copyright © 2005 by Jeremy Brecher